Democracy, Democratization, and Development in Post-Cold War Africa (1990-2012)

1Department of Social Sciences and Criminal Justice, Benedict College, Columbia, USA .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.1.2.02

Copy the following to cite this article:

Ratsimbaharison A. M. (2018). Democracy, Democratization, and Development in Post-Cold War Africa (1990-2012). Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 1(2).

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.1.2.02

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Ratsimbaharison A. M. (2018). Democracy, Democratization, and Development in Post-Cold War Africa (1990-2012). Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 1(2).

Available From: https://bit.ly/2BowKwS

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 22-8-2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 20-11-2018 | |

| Plagiarism Check: | Yes | |

| Reviewed by: |

Ntokozo Mthembu

Ntokozo Mthembu

|

|

| Second Review by: |

Fatima Mmusi

Fatima Mmusi

|

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Christopher Vasillopulos | |

The relationships between democracy and development have been the subject of countless speculations and research projects for some time. Thus, a few decades ago, some modernization theorists suggested that economic development, through different intervening variables such as the improvement of the education and the emergence of a strong middle class, would eventually lead to democracy in dictatorial regimes. Seymour Lipset was one of the first who made this prediction in the 1950s. In his seminal work on Some Social Requisites of Democracy, he makes the argument that economic prosperity would give rise to a literate middle class, which would espouse liberal values and seek to defend its newly acquired assets through the institution of democratic political systems. However, several historical facts (e.g., the persistence of dictatorship in China, despite its huge economic successes in recent years) and the findings from different studies have proven this prediction to be wrong.

Since the triumph of capitalism and democracy at the end of the Cold War, the so-called “democracy promoters” made another argument that democracy along with capitalism would be the best political system to promote rapid economic development in the developing countries. Thus, promoting democracy around the world became one of the major components of the foreign policies of most developed countries, such as the United States. However, faced with the inability of many democratic countries to solve their own economic problems and the failure of some of them to even stay alive, particularly in Africa, this argument has now become all the more questionable.

This research project deals with the latter argument. It addresses the questions of whether democracy would be better than any other political systems to promote development in Africa and whether democratic and/or democratizing countries have better economic performances than the other African countries.

Following a quick review of the existing literature concerning the relationship between democracy and development, the methodology, including the data, the statistical procedures, and the software used to carry out the analysis will be presented. Next, the findings will be discussed along with the tables and graphs. Finally, the paper will draw the main conclusions and suggest new directions for future researches.

Some scholars are categorical in their findings that democracy does not lead to development (or better economic performance). Among these scholars, Doucouliagos and Ulubasoglu, using “meta-regression analysis to the population of 483 estimates derived from 84 studies on democracy and growth,” draw the conclusion that: “democracy does not have a direct impact on economic growth” . The findings of Przeworski et al. and Diebolt et al. seem to confirm this hypothesis of no direct effect of democracy on development. Indeed, Przeworski et al. look at the data from 135 countries between 1950 and 1990, and draw the conclusion that economic development does not generate democracies, as in the case of a country like China, but “democracies may be more likely to survive in wealthy societies”. In other words, instead of finding the direct effect of democracy on development, they come up with the reverse effect of development on democracy survival. In the same vein, Diebold et al. confirm the inability of democracy to solve economic problems and suggest that: “democratic poverty trap is found to exist indicating the possibility of persistence of (un)stable democratic equilibria at different levels of democracy”.

Among the scholars who support the hypothesis of the direct effect of democracy on development, Masaki and van de Walle “find strong evidence that democracy is positively associated with economic growth, and that this ‘democratic advantage’ is more pronounced for those African countries that have remained democratic for longer periods of time” . However, most of the scholars who also find this direct effect are more nuanced in their assertion. Thus, Carl LeVan makes the argument that “the key factor is not simply the status of the regime as a dictatorship or a democracy, but rather it is the structure of the policy-making process by which different policy demands are included or excluded”. In the case of Botswana, which is one the success stories of democracy and development in Africa, Acemoglu et al. draw the following conclusion: “Botswana achieved this rapid development by following orthodox economic policies. How Botswana sustained these policies is a puzzle because typically in Africa, ‘good economics’ has proved not to be politically feasible. In this Paper, we suggest that good policies were chosen in Botswana because good institutions, which we refer to as institutions of private property, were in place”.

Methodology

This research project uses data on development and economic performance from the World Bank and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in combination with data on regime characteristics from the Polity IV Project and Freedom House. These data are analyzed using the statistical software SPSS.

According to UNDP’s people-centred approach, development is understood as follows: “Human development aims to enlarge people’s freedoms to do and be what they value and have reason to value [.]. At all levels of development, human development focuses on essential freedoms: enabling people to lead long and healthy lives, to acquire knowledge, to be able to enjoy a decent standard of living and to shape their own lives” . In line with this view, development is measured in this study, not only in terms of the traditional World Bank’s GNI (gross national income) per capita but also in terms of the UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI).

Following Larry Diamond’s dual conception of democracy, the concept of democracy is defined in this study, not only as “a system for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote”(thin side), but also as a system ensuring, among other attributes: “substantial individual freedom of belief, opinion, discussion, speech, publication, broadcast, assembly, demonstration, petition, and (why not the internet”(thick side) . Thus, in order to capture the different attributes of democracy, Polity IV’s scores of regime characteristics are used alongside Freedom House’s scores of political rights and civil liberties.

Findings

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 1, below, the democratization of Africa really started at the end of the Cold War, when the number of democratic or “free” countries increased from two (2) in 1989 to 9 in 1993. However, since then, the democratization of the continent was stalled, as the number of democracies oscillated around nine (9).

Table 1: Frequencies of Regime Types in Post-Cold War Africa (1989-2012)

|

Survey Edition |

Free |

Partly Free |

|

|

Number of Countries |

Percentage |

Number of Countries |

|

|

1989 |

2 |

4 |

12 |

|

1990 |

3 |

6 |

11 |

|

1991 |

4 |

8 |

15 |

|

1992 |

8 |

17 |

19 |

|

1993 |

9 |

19 |

23 |

|

1994 |

8 |

17 |

15 |

|

1995 |

8 |

17 |

17 |

|

1996 |

9 |

19 |

19 |

|

1997 |

9 |

19 |

19 |

|

1998 |

9 |

19 |

18 |

|

1999 |

9 |

19 |

20 |

|

2000 |

8 |

17 |

24 |

|

2001 |

9 |

19 |

24 |

|

2002 |

9 |

19 |

25 |

|

2003 |

11 |

23 |

21 |

|

2004 |

11 |

23 |

20 |

|

2005 |

11 |

23 |

21 |

|

2006 |

11 |

23 |

23 |

|

2007 |

11 |

23 |

22 |

|

2008 |

11 |

23 |

23 |

|

2009 |

10 |

21 |

23 |

|

2010 |

9 |

19 |

23 |

|

2011 |

9 |

19 |

22 |

|

2012 |

9 |

18 |

21 |

|

Source: Freedom House (2013). Country Status by Region. |

|||

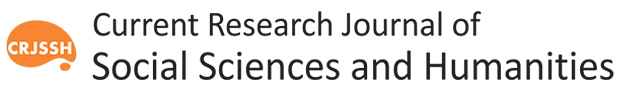

Table 2: Frequencies of Political Transitions in Post Cold War Africa (1989-2012)

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

|

|

Valid |

No political transition |

876 |

68.9 |

71.9 |

71.9 |

|

Transition to democracy (democratization) |

203 |

16.0 |

16.7 |

88.5 |

|

|

Transition to autocracy (autocratization) |

140 |

11.0 |

11.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

1219 |

95.8 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Missing |

System |

53 |

4.2 |

|

|

|

Total |

1272 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 - Political Transitions in Post-Cold War Africa (1989-2012) |

Table 3: Evolution of the Average GNI per capita in Post Cold-War Africa (1989-2012)

|

Year |

Average GNI per capita |

N |

Std. Deviation |

|

1989 |

832.88 |

52 |

1020.262 |

|

1990 |

858.43 |

51 |

1085.765 |

|

1991 |

910.20 |

49 |

1144.653 |

|

1992 |

945.21 |

48 |

1235.693 |

|

1993 |

906.12 |

49 |

1231.515 |

|

1994 |

877.96 |

49 |

1246.931 |

|

1995 |

893.27 |

49 |

1254.513 |

|

1996 |

927.55 |

49 |

1303.084 |

|

1997 |

952.20 |

50 |

1362.215 |

|

1998 |

928.00 |

50 |

1329.012 |

|

1999 |

894.60 |

50 |

1283.416 |

|

2000 |

899.60 |

50 |

1303.112 |

|

2001 |

907.40 |

50 |

1310.589 |

|

2002 |

948.40 |

50 |

1356.653 |

|

2003 |

1028.00 |

50 |

1464.638 |

|

2004 |

1186.27 |

51 |

1644.711 |

|

2005 |

1474.04 |

52 |

2016.400 |

|

2006 |

1669.62 |

52 |

2330.228 |

|

2007 |

1910.38 |

52 |

2742.845 |

|

2008 |

2195.00 |

52 |

3136.953 |

|

2009 |

2296.92 |

52 |

3328.962 |

|

2010 |

2115.88 |

51 |

2828.888 |

|

2011 |

2266.27 |

51 |

3119.592 |

|

2012 |

2183.33 |

51 |

3109.808 |

Sources: The World Bank, Gross National Product per Capita, Atlas Method (US current dollar)

Table 4: Evolution of the Classification of the African Economies

|

|

Low Income |

Lower Middle Income |

Upper Middle Income |

High Income |

Total |

|

1989 |

42 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

52 |

|

1990 |

42 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

51 |

|

1991 |

39 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

49 |

|

1992 |

36 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

48 |

|

1993 |

39 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

49 |

|

1994 |

38 |

9 |

2 |

0 |

49 |

|

1995 |

38 |

10 |

1 |

0 |

49 |

|

1996 |

37 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

49 |

|

1997 |

38 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

50 |

|

1998 |

38 |

11 |

1 |

0 |

50 |

|

1999 |

38 |

11 |

1 |

0 |

50 |

|

2000 |

37 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

50 |

|

2001 |

37 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

50 |

|

2002 |

37 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

50 |

|

2003 |

37 |

10 |

3 |

0 |

50 |

|

2004 |

38 |

9 |

4 |

0 |

51 |

|

2005 |

37 |

8 |

7 |

0 |

52 |

|

2006 |

35 |

10 |

7 |

0 |

52 |

|

2007 |

34 |

11 |

7 |

0 |

52 |

|

2008 |

28 |

15 |

7 |

2 |

52 |

|

2009 |

25 |

18 |

8 |

1 |

52 |

|

2010 |

26 |

16 |

8 |

1 |

51 |

|

2011 |

25 |

18 |

7 |

1 |

51 |

|

2012 |

26 |

18 |

6 |

1 |

51 |

|

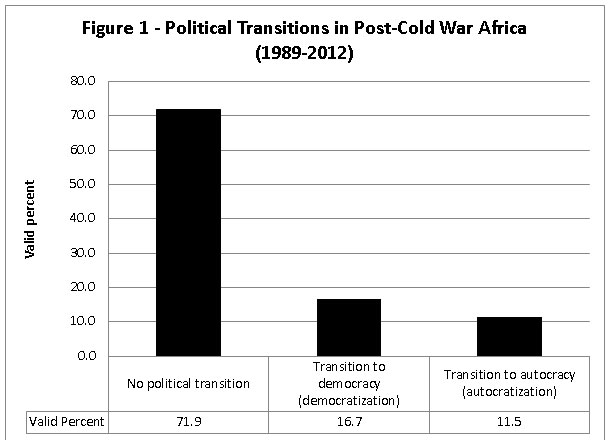

Figure 2: Classification of the African Economies in 2012 Click here to view figure |

Table 5a: Correlations between HDI, Polity IV Scores and Freedom House's Combined Average Scores of Political Rights and Civil Liberties

|

|

Human Development Index (measuring achievement in health, knowledge, and standard of living). |

Polity IV Scores (measuring the level of democracy or autocracy) |

Freedom House's combined average scores of political rights and civil liberties |

|

|

Human Development Index (measuring achievement in health, knowledge, and standard of living). |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.103 |

-.204** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.063 |

.000 |

|

|

N |

339 |

323 |

339 |

|

|

Polity IV Score (measuring the level of democracy or autocracy) |

Pearson Correlation |

.103 |

1 |

-.803** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.063 |

|

.000 |

|

|

N |

323 |

1223 |

1223 |

|

|

Freedom House's combined average score of political rights and civil liberties |

Pearson Correlation |

-.204** |

-.803** |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

N |

339 |

1223 |

1276 |

|

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 5b: Correlation between GNI per Capita, Polity IV Scores and Freedom House's Combined Scores

|

|

GNI per Capita, Atlas Method (US current dollar) |

Polity IV Scores (measuring the level of democracy or autocracy) |

Freedom House's combined average scores of political rights and civil liberties |

|

|

GNI per Capita, Atlas Method (US current dollar) |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.099** |

-.165** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.001 |

.000 |

|

|

N |

1210 |

1174 |

1210 |

|

|

Polity IV Score (measuring the level of democracy or autocracy) |

Pearson Correlation |

.099** |

1 |

-.803** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.001 |

|

.000 |

|

|

N |

1174 |

1223 |

1223 |

|

|

Freedom House's combined average score of political rights and civil liberties |

Pearson Correlation |

-.165** |

-.803** |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

N |

1210 |

1223 |

1276 |

|

|

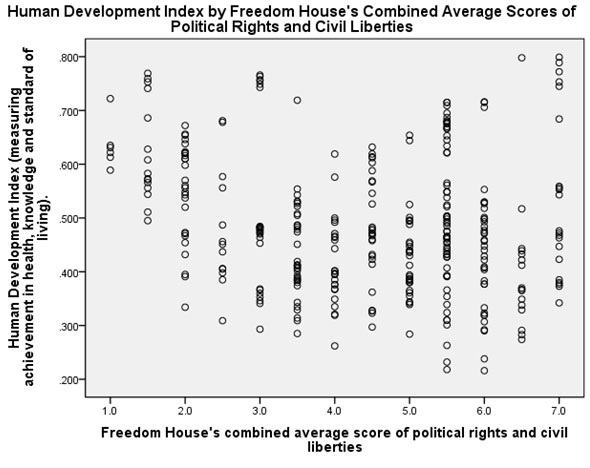

Figure 3: Scatterplot: Human Development Index by Freedom House’s Combined Average Scores of Political |

Table 6: Economic Performance Five Years Before and Five Years After Full Democratization

|

|

Human Development Index (measuring achievement in health, knowledge, and standard of living). |

Gross National Product per Capita, Atlas Method (US current dollar) |

Annual percentage growth of the Gross Domestic Product |

|

|

No democratization |

Mean |

.47701 |

1294.29 |

3.760 |

|

N |

280 |

1004 |

967 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

.129638 |

2130.592 |

8.0272 |

|

|

Five years before democratization |

Mean |

.41180 |

747.00 |

3.180 |

|

N |

10 |

60 |

60 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

.112161 |

842.157 |

3.2779 |

|

|

Five years after democratization |

Mean |

.52719 |

1568.84 |

4.887 |

|

N |

48 |

146 |

138 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

.086996 |

1542.384 |

4.5403 |

|

|

Total |

Mean |

.48221 |

1300.28 |

3.864 |

|

N |

338 |

1210 |

1165 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

.125550 |

2027.267 |

7.5235 |

|

References

- Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53(01), 69–105.

CrossRef - See particularly, Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Carson, J. (2013). The Obama Administration’s Africa Policy: The First Four Years, 2009–2013. American Foreign Policy Interests, 35(6), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803920.2013.855549

CrossRef - Doucouliagos, H., & UlubaÅŸoÄŸlu, M. A. (2008). Democracy and Economic Growth: A Metaâ€Analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 61–83.

CrossRef - Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; and Diebolt, C., Mishra, T., Ouattara, B., & Parhi, M. (2013). Democracy and Economic Growth in an Interdependent World. Review of International Economics, 21(4), 733–749.

CrossRef - Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 88.

CrossRef - Diebolt, C., Mishra, T., Ouattara, B., & Parhi, M. (2013). Democracy and Economic Growth in an Interdependent World. Review of International Economics, 21(4), 733–749.

CrossRef - Masaki, T. (2014). The Political Economy of Aid Allocation in Africa: Evidence from Zambia. Retrieved from http://takaakimasaki.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Zambia_Draft_2014-12-3.pdf, p. 1.

- LeVan, A. C. (2014). Dictators and Democracy in African Development: The Political Economy of Good Governance in Nigeria. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, Summary.

CrossRef - Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2002). An African success story: Botswana (Working Paper 01-37). Cambridge, MA: Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved from http://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/63256/africansuccessst00acem.pdf, p. 1.

- Alkire, S. (2010). Human Development: Definition, Critiques, and Related Concepts. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdrp_2010_01.pdf, p. 43.

- Diamond, L. J. (2008). The Spirit of Democracy: The Struggle to Build Free Societies Throughout the World. New York, New York: Henry Holt and Company, pp. 21-22.

- Mitterand, F. (1990, June 20). Le discours de La Baule (1990). Retrieved from https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB461/docs/DOCUMENT%203%20-%20French.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.