Proliferation of Tribal Migrants and Repercussion: Case Study from the Tribal Areas of Sundargarh District, Odisha (India)

Roshni Kujur  and Sumit Kumar Minz

and Sumit Kumar Minz

1Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.4.1.04

Copy the following to cite this article:

Kujur R, Minz S. K. Proliferation of Tribal Migrants and Repercussion: Case Study from the Tribal Areas of Sundargarh District, Odisha (India). Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2021 4(1). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.4.1.04

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Kujur R, Minz S. K. Proliferation of Tribal Migrants and Repercussion: Case Study from the Tribal Areas of Sundargarh District, Odisha (India). Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2021 4(1). Available From : https://bit.ly/35CPEy8

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 20-03-2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 09-06-2021 | |

| Reviewed by: | Dr. Ishrat Naaz | |

| Second Review by: | Udayanga, K.A.S | |

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Riccardo Pelizzo | |

Introduction

Migration in India involves a long history of humankind about human mobility in search of new destination and opportunities for saken from their origin to discover a life unseen. In the 1990s, the emergence of the agrarian crisis in India, with a serious shift in policymaking intensified the farmers to rely upon the moneylenders, due to this rapid migration appeared as an appropriate option for restoring rural livelihood. An article published in The Hindu, 2011 indicated that the rising imbalance across the regions has raised new phases and disparities and human migration has created a hallmark “the human flow became a flood.”1 The consequences of migration have changed its outcome with a different mode in both economic and social order in the walks and works of the migrants. At present migration has been seen as the most debatable political agenda discussed and consulted globally. The trend of migration has seen to be inclined downwards, where people willingly leave their homelands for financial assistance or other reasons and even some while enforced to leave their land and soil in search of a better livelihood.2 As Farely indicates “migration as mostly about survival, but also a bit about the adventure” as migration seems to render positive opportunities provided to the rural masses to experience their life in the city.3 But arguably recent surveys and analyst of migration has engrossed a captive narration, where the voices of these migrants are compressed and suppressed under the sound of their heavy-laden situation. Anthropologists implicate the analysis of migration to narratives of modernity or progress.4 Many developers and environmentalists viewed migration interrogated as an objective of decline, loss, de-peasant nation and the formation of 'ecological refugees'.5 Migration has been identified as a historical process in shaping human history, economy and culture, simultaneously influencing the demand and supply of labours in the market, rapid economic growth and subsequently the tentative reflection on human well-being. The variant folds of migration often affect the lives of the migrants as per the appearance of unconditional circumstances includes long hours work schedule, inadequate living and working circumstances, social segregation and poor access to basic needs and benefits.6 The migrants share their stories full of distress, condemned life and broken dreams, bringing the migrant labour markets as a failing system to enable the migrant workers to redress from poverty, but the hazardous working condition with highly repressive living situations vanishes their hopes in the darkness.

Almost 90 per cent of the total tribal population lives in rural India as regards this tribal migration determines a different pattern.7 The tribal community has always been a descendant of Land and Forest from the very beginning and fully or partially depended upon nature for their survival and daily affairs. However, tribal migration has a long history since the 19th century, as being forced out of their homeland by the colonial policy as they joined plantations, mines and even factories, as investing in them was cheap and committed. Migration was the result of the double edge colonial policy of land alienation and labour recruitment.8 Further, indebtedness, inadequate food security, lack of local work, low wages or late payment of wages in their native areas are primarily seen as the major factors of tribal trading out-migration.9 Tribal land and forest are a huge place for investment for constructing dams and water bodies, power factories, industrialization and excavating the land for mining further creating money for establishing the nation and employment opportunities for others, whereas tribals remain at the end hopelessly. Hardly benefitting the tribes rather makes the way to their social and cultural deprivation, displacement and land alienation, that too without any proper rehabilitation. Excavating the natural resources has exploited the tribals, virtually displacement leading to the denial of the basic rights of livelihood and existence. Thus tribal migration paradoxically regarded as the only means as these aboriginals has erased from their land and forest-dependency life, which has reciprocated their means of survival and intruded moral risk.

This movement of people has always been a greater concern for the government and various measures have been initiated, to overcome the crisis faced by the migrants. Yet it looks afar from the goal to immobilize the issue of protracted migration within the territorial boundary of the country. According to the Census report 2011, 45.36 crores (37%) of Indians, overtaking 31.45 crores according to the previous Census report of 2001 are migrants, residing in various places other than their native land.10 The rural population of the country is largely heading towards the urban areas with at least 25-30 people per minute for a better livelihood.11 According to data provided by United Nations the urban population in India has raised from 17.1 per cent in 1950 to 29.2 per cent in 2015 whereas the rural population has declined from 82.9 per cent in 1950 to 67.2. It also predicts that by 2050 the segregation of urban-rural population likely is 52.8 and 47.2 with a difference of 5.6 per cent.12

In recent times Odisha has observed, ‘tribal migration’ has a possible effect among the scheduled areas as economically demolished and socially excluded due to acute displacement and land alienation in name of development leading a critical living condition and their sustainability to restore their households, now depends on migration. Simultaneously, the present research has looked down to the nature of migration, which has never been the option for the tribal population. Such forced migration has never upheld the benefitting factor in accumulating capital, to look beyond the horizon of progress in their living standards, but to fulfil their basic needs, which was taken care of by the mother earth (Water, Land and Forest). This new category of tribal migrants are comprised of unskilled work profile, casual labour lacking social preservation, informal recruitment sources, and engaged in the informal sectors under exclusively hazardous conditions, later on, end up with bondage. The basic complications that rose for the reason to migrate from their ancestral rural regions are constant rural poverty, food insecurity, unemployment and income-generating possibilities, social inequality, limited access to social protection.13 Natural calamities, Displacement, agro-based unemployment or lack of opportunities in the greater form of cultivation are playing a remarkable impact on discontent, spreading among the rural populations.14 The urge for migration was absent as long as the wants were satisfied from the local sources. But the deep-rooted socio-economic discrimination and loopholes in governmental policies have pushed the poor tribal people into the picture of migration. The prime focus of this study is “to examine and enquire the perceptions about migration among Tribals of Sundargrah district, Odisha and the impact on their lives”.

Concept and Theoretical Framework

Migration is a complex phenomenon driven in society through various forces both at the micro and macro level. Theoretically, migration has been studied by various theorists as; Everett Lee observed migration in 1966 popularly known as ‘Push and Pull Theory’ interrogates the volume of migration within the territory relating to their origin and destination. The theory relates four major factors associated with the area of origin, area of destination, Intervening obstacles and personal factors influencing them to migrate for a better existence.15 Whereas, the dual labour market theory indicates the core reason behind the migration of labour based on pull factors, such as; raising employment opportunities, the possibility of high wages, better source to livelihood, urbanization, convincing the migrants to mobilise towards developed regions.16 According to Wallerstein, the expansion of modern states has put a phenomenal impact on the economic, political and legal framework indicated as the “World System” to understand the compound idea of globalization in individual societies and nation-states. The theory links migration as a flow process in the structural change of world capital mobility, where migration is the natural outgrowth due to interruption and disconnection necessarily occur due to capitalist firms enter in poor countries on the perimeter of the world economy in search of land, raw materials, labour and new consumer markets. These links facilitate the movement of goods, products, information, and capital, and even endorse the movement of people.17 E. G. Ravenstein’s laws of migration indicate that the migrants prefer short distance migration to fill up as well as the long-distance for commerce and industrial purposes, the process of absorption, law of dispersion, the flow of migration on compensating flow, women migration, economic instability and opportunities in industry or market place. Even his observation, incorporates and examines that females migrate more than males and inhabitants of rural areas are more migratory than the urban area's dwellers.18 Whereas as analysing the Neo-classical theory indicates that migration probably occurs due to wage differences and varying employment conditions in comparison to two different locations, which become the key driving forces behind the movement of people from a low wage region to a region with high wages and better assignments.19

For a clear understanding of the different trends of migration, both push and pull factors, depending on the origin and destination brings a clear recognition to its perspectives. Illiteracy, low income, poverty, dependence on agriculture are associated with the place of origin, pushing them to move, for a better option, whereas high literacy, high income, employment opportunities, the dominance of industries and services at the destination encourages (pull) to move from their impoverished situation.20 The study by Bhagat (2011) denies the most believed fact that most migration takes place from the disadvantaged section of Indian society. He further argues that the push factor doesn’t influence much the permanent and semi-permanent migration.

The study by Mosse et al. (2002)21 reveals a different picture of tribal migration, just contrary to the argument of Bhagat. It states that migration among tribals is more involuntary, mostly due to poverty and indebtedness. Further, it explores that individuals including women, mostly belonging to poorer household undertake long-term and long-distance migration.

Jha (2005)22 point of analysis is the outcome of a workshop organised by the Indian Social Institute, New Delhi, in Sundargarh district of Odisha states that push factors are primarily responsible for the migration of young tribal women to the metropolitan cities like Delhi and Mumbai, mainly for domestic household works. He clearly states that migration is not a matter of choice but more a compulsion to avoid starvation.

Veerabhadrudu and Subramanyam (2013)23 conduct a study that deals with the sufferings and turbulence experienced by the displaced tribal people due to the construction of dams and reservoirs forcing (Push) them to migrate and adopt a new destination. Simultaneously, such involuntary displacement brings the inadequate flow of marginalised people carrying the consequences of landlessness, food insecurity, and loss of natural resources and social isolation.

Chandra and Paswan (2020)24 explore the attitude and perception about migration among one of the largest tribal communities in India by conducting a primary field study at the Ranchi district of Jharkhand. It indicates that one-third of the respondents agree that migration assists them to pursue the education of their own choice and helps to improve the economic condition of their family. It further states that a majority of the respondents believe that migration can help to generate employment opportunities and can bring socio-economic development to their family.

Patel and Giri (2019)25 analyse the status of migrant women working in different construction sites in the coastal districts of Odisha. They conducted this study particularly in Bhubaneswar where women migrants, mostly illiterate and landless, belonging to Scheduled Caste forced to migrate basically due to repeated natural calamities like flood. Migration seems to help these migrant women to improve their financial status and living condition and re-boost their self-confidence to overcome entrenched social barriers. Meanwhile, the study claims that women of the same group living in other areas continue to face a different form of marginalisation and vulnerabilities to a great extend.

Study Area

Odisha State

Odisha is one of the most prominent states of India, surrounded by natural ambience and homeland of indigenous tribal communities’ with unique culture distinct. Odisha was recognised as a separate province by the British during colonial rule on 1st April 1936, with is celebrated as Utkal Divas (Odisha Day).26 The heart of the Odisha, Bhubaneswar is the present capital of the state, whereas Cuttack remained as its capital till 12th April 1948.27 According to the census report the total population of the state is outlined to be 41,947,358 out of which 21,201,678 (50.54%) are male and 20,745,680 (49.46%) are female.28 Besides, these Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Caste constituted 22.85 and 17.13 per cent respectively, totalling 38.66 per cent of the total population of Odisha.29 The state is inhabited by 62 tribal communities,30 which is highest as compared to other states, out of 705 scheduled tribes are enlisted by the government of India, contributing 9.2 per cent of the total tribal population of India.31 A majority number of tribal population abode in Kandhamal, Koraput, Malkangiri, Mayurbhanj, Nabarangapur Rayagada and Sundargarh districts, declared as 5th Scheduled Areas by the government of India.32 Tribal economy survives in nature and it revolves around the forest, from gathering food to collecting all types of Non-timber forest products.

Sundargarh Area

Sundargarh district was formed out of two ex-states namely Gangpur and Bonai on 1st January 1948 and simultaneously converged in Odisha. It comprises 17 Blocks divided into 3 Sub Divisions, namely, Sundargarh, Panposh and Bonoi.33 The Demography of Sundargarh in total is 20,80,664 consisting of 10,61,147 males and 10,32,290 females. Further comprises a total of 10,62,349 (50.75%) Scheduled Tribes and 1,91,660 (9.16%) Scheduled Castes population.34 It is recognized and declared as one of the Scheduled Areas by the government of India as more than 50 per cent of the total population in the district are tribals. Geographically the district is abundant with natural resources, as 40.4 per cent of its total land is covered by forest.35 Yet, dwellers of these mineral-rich regions, the tribals still respires amidst the adversity of poverty and underdevelopment.

Land Forest and Tribal Migration

The census report 2011 indicated poverty line among the tribal in rural Odisha is 39 per cent in comparison to 25 per cent among Scheduled Castes and 36 per cent others. Further, the tribals settled in rural belts of Odisha, the poverty percentage is highest than others i.e., 67 per cent in compared of other sections of the society, 50 per cent among the poorest of rural Odisha are the tribals and the poorest household carrying the labour type is 54 per cent again counted among the tribals.36 Though there is increasing recognition in policy-making for the tribes in the state, they fall always behind in the development parameter. In addition, the tribals are tremendously facing the consequences of losing their land and forest due to the excavation and deforestation done in the tribal mineral-rich habitant, including a serious note of compromising the lives of the tribals incorporating them in the line of ‘Migration’. Tribal people are closely associated with nature, and they wholesomely depend upon forest products, land cultivation and natural resources, as the main source of economy and sustenance. Tribal areas are abundantly flourished with mineral resources and have regularly attracted many private sector industrialists for digging mines and establishing industrial hubs. From generation to generation the tribals have de-facto accessibility on the forests land and resources but due to poor recognition through documentation, the tribals are unable to convert it under their ownership and their source of livelihood. Studies estimate that more than 50 per cent of tribal land in Odisha has been lost to non-tribals, through illegal means over 25-30 years through indebtedness, mortgage and forcible possession, the worse process of tribal alienation.37 Alienation together with reduced income from NTFPs, stagnant agriculture and limited opportunities for non-farm self-employment, push tribal households into a cycle of high-interest debt from private moneylenders resulting in food insecurity and forced migration.38

Tribals have an enormous share in the development process, as Odisha’s multi-dimensional growth, depends on the mineral resources predominantly underneath the tribal inhabitants. Setting up of mineral-based industries in these pockets has therefore resulted in large scale displacement of tribals from their traditional land with no proper courtesy of resettlement and rehabilitation for these poor innocent tribals.39 Such alienation and immorality of the governmental policies has not surprisingly, brought tribal deprivation but even pushed them in the crowd of migration populations trading in the flock of disparities and discrimination. Yet, tribals are forgotten by the government whose land and forests are used to bloom the economy. It is observed that the proper and effective process of Resettlement and rehabilitation is not followed by the governmental agencies and other institution at most of the time which ultimately push tribal people to migrate to various parts of the country to survive as tribals mainly depend on land and forest. Moreover, as the primary occupation of tribal is based on agricultural products, they seek more irrigation facilities other than depending upon the monsoon rain. Often the agriculture becomes the gamble of monsoon and farmers don’t get the minimum price for their products, neither the government intends to be interested in the issue to provide minimal support price. Ultimately tribals find one way out and very often leave their children and families stepping out from their native place to different parts of the country in search of a job to feed themselves and their families left behind. Government data reveals that “There are 90 districts or 809 blocks with more than 50 per cent of tribal population and they account for nearly 45 per cent of the tribal population in the country. In simple words, almost 55 per cent of the tribal population has migrated from their native land and lives outside these 809 tribal majority blocks.”40

Data Sources and Research Methodology

Odisha sends around 1.5 million seasonal migrants into a distinctive pattern of labour to different regions. To make the study too precise and define the rate of migration empirical intensive field study method is adopted so one district from western Odisha has been proposed for research as densely populated by Scheduled Tribes i.e., Sundargarh. The research identifies Sundargarh District carries 17 blocks among which four blocks been selected for the study as Balisankara, Kaurmunda, Rajgangpur and Subdega. Balisankara comprises 57,427 ST population, Kuarmunda of 82,264 ST population respectively through systematic random sampling method. Rajgangpur is stated as industrial cum rural area, which has a large tribal population of 85,116. Their main occupation is farming, collecting forest products and work in nearby small factories. Subdega is a rural area that consists of 45,332 tribal populations. Table 1 highlights the population of the selected study area where the majority of them belong to the tribal community. It also indicates that the entire populations of Subdega and Balisankra block live in rural areas.

Table 1: Detail Population of the Study Area.

|

Sl. No. |

Name of Blocks |

Number of Panchayat |

Number of Villages |

Number of Households |

Population |

Male |

Female |

ST Population |

Male |

female |

||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

Total |

Rural |

Urban |

Total |

|||||||||

|

1 |

Subdega |

14 |

63 |

15,517 |

64,254 |

- |

64,254 |

31,951 |

32,303 |

45,332 |

- |

45,332 |

22,433 |

22,899 |

|

2 |

Balisankra |

16 |

101 |

21,656 |

85,690 |

- |

85,690 |

42,087 |

43,603 |

57,427 |

- |

57,427 |

28,060 |

29,367 |

|

3 |

Kuarmunda |

20 |

108 |

23,055 |

97,870 |

9,043 |

1,06,913 |

53,460 |

53,453 |

78,591 |

3,673 |

82,264 |

40,933 |

41,331 |

|

4 |

Rajgangpur |

12 |

77 |

22,391 |

95,142 |

9,923 |

1,05,065 |

52,401 |

52,664 |

79,124 |

5,992 |

85,116 |

42,285 |

42,831 |

(Census of India 2011, District Census Handbook, Sundargarh)

The primary data collection based on intensive fieldwork has been taken to understand the socio-economic conditions and the different nature and trends of migration among the rural tribals. Data has been collected from four selected blocks of Sundargarh district of Odisha, through random and purposive sampling adopted for enquiry and data analysis, as indicated in table 2. Some 50 household samples from each block and a (both male and female migrants, women-headed households) total 200 respondents have been examined. Scheduled questionnaire and interview method are used as a technique of data collection during fieldwork. Observation and focused group discussion is also used as a tool to accumulate ground reality of the study area. Per to collect secondary data regarding the literature of the subject, different published books, journals, government records and census reports were observed.

Table 2: Sample of Respondent.

|

Sl. No. |

Name of Blocks |

Respondent |

||

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

||

|

1 |

Subdega |

38 |

12 |

50 |

|

2 |

Balisankra |

40 |

10 |

50 |

|

3 |

Kuarmunda |

35 |

15 |

50 |

|

4 |

Rajgangpur |

39 |

11 |

50 |

|

Total |

152 |

48 |

200 |

|

|

Percentage |

76 |

24 |

100 |

|

Tribal Migrants and their Socio-Economic Profile

About 93.78 per cent of tribals in Odisha live in rural areas41 as against 90 per cent in India.42 Majority of these tribals lives in hilly and forest regions. Illiteracy and poverty rate among tribes in Odisha have been consistently high as 47.8 per cent and 50.05 per cent respectively and hence inequality and social disparity still prevail in the society.43 Table 3 reflects the age groupings of the tribal migrants, both male and female classified to learn their order of migrating as well as their socio-economic background. Tribals are much associated with their homeland and family. Due to acute poverty, debt, and land alienation the tribal comes under the vulnerability category. From the total respondents around 50.65 per cent of male migrants and 50 per cent of female migrants are unmarried, whereas 47.36 and 41.66 per cent of male, as well as female migrants, are married respectively. Lack of proper accessibility of employment and well-paid dues, push them into the phase of migration and are forced to leave behind their families and move on to a new destiny to explore and earn for them. The young age migrants are counted from 18-24 years were 54.16 per cent of tribal girls have migrated to various cities in carrying domestic households and working in fish packaging industries from this age group. Similarly, the male tribal migrants of the same age groups count to 48.68 per cent as being the highest age group to migrate to various labour market such as in factories, automobile stations followed by the early middle age group 47.36 working in fish farming, construction sites, pig farming etc. By the age of 46 years and above, it has been examined that the migrants retire and return to their respective homelands.

Table 3: Socio-Economic Profile of Tribal Migrants.

|

Variables |

Division of Variables |

Number of Respondents (Male) in per cent |

Number of Respondents (Female) in per cent |

|

Age |

1.Young Age (18- 24 years) 2.Early Middle Age (25-45 Years) 3. Middle Age (46-54 Years) |

48.68 47.36 3.94 |

54.16 39.58 6.25 |

|

Training |

1.Skilled 2.Semi-Skilled 3.Unskilled |

5.92 53.28 40.78 |

00 27.08 70.83 |

|

Marital Status |

1.Married 2.Unmarried 3.Divorced 4. Widow/Widower |

47.36 50.65 00 1.97 |

41.66 50 2.08 6.25 |

|

Educational Qualification |

1.Primary(Nursery-Class V) 2.Secondary (IV to VII) 3.Higher Secondary (VIII to X) 4.College (+2 to Higher Studies) 5.Illeterate |

15.13 22.36 47.36 7.89 7.23 |

14.58 22.91 43.75 6.25 12.5 |

|

Occupation |

1.Ordinary Labour 2.Agriculture 3.Any Other |

33.55 61.18 5.26 |

37.5 58.33 4.16 |

|

Income |

1.High Income (9001-13,000) 2.Middle Income (6001-9000) 3. Average Income (3001-6000) 3.Low Income (Below 3000) |

1.31 3.28 28.28 67.10 |

00 5 20 75 |

In the labour market the Adivasi migrants despite their skills they are highly segregated in these cities as they are excluded from skilled work as masons, carpenters or textile workers, and ensures that they are absorbed almost entirely as the lowest-paid, unskilled labour.44 Through the extensive study it is recorded that around 53.28 per cent of tribal migrants are placed semi-skilled, whereas 5.92 per cent of them are skilled workers. Some of them are ITI trained in mechanical and electrical skill works, further among them are skilled masons and carpenters. They are identified as unskilled manual workers in construction sites, automobile factories in brick Kilns and never been able to acquire their skills or better-paid work. As per the 2011 census, the overall literacy rate in Odisha is 72.87 per cent whereas the literacy rate among tribes is 52.24 per cent only. The literacy rates of tribal male and female are 63.70 and 41.20 per cent respectively.45 Over the last decade, there is an improvement as an increase from 37.4 per cent in 200146 to 52.24 per cent in 2011.47 In accordance to the research it shows the tribals in the study area acquired Higher Education (Class VIII- X) as 47.36 per cent male and 43.75 per cent female respectively.

As per the 2011 census report more than the two-third tribal population is working in the primary sector (as against 43 per cent of the non-tribal population), and is predominantly dependent on agriculture either as cultivators or as agricultural labourers.48 Agriculture is the mainstay of the tribals, about 61.18 and 58.33 per cent of male and female migrants yield in their land in accordance to the study and economical background. At present 17 per cent of the state economy is disfigured due to low irrigation facilities, minimal groundwater sources, low technological inputs and poor crop yields, simultaneously lowering the agricultural values.49 Tribal economy have a low rate of income of Rs 3000 or even less per month approximately as 67.10 and 75 per cent (male and female) respectively, comes under this category in the area of research. With the lowest probability of survival, the tribal population is increasingly moving from being cultivators to agricultural labourers and then further enters the informal labour market, with new hopes.

Result and Discussion

Destination of Migration

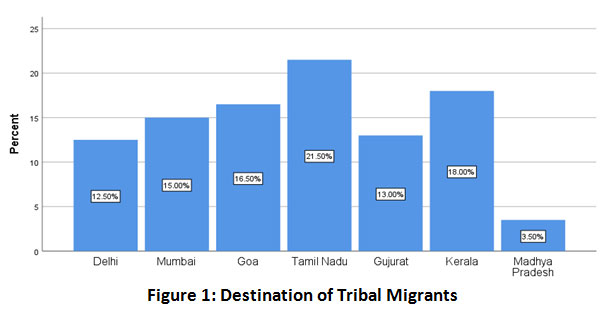

Each migrant have their stories and reasons to migrate, some have to repay the debt, some have lost their land due to industrialization, some to collect money to feedback their families and some young folks has to explore the city-style. But the consequences bring a miserable reward of bondage, loss or possible death, disability due to hazardous working conditions as so. Such turn out points, that livelihood security at the destination is the lowest concern of development regarding the migrants' context. The Census report of 2011 indicates a sharp decline of 32 per cent in the number of villages with 100 per cent tribal population between 2001 and 2011, moving to cities in search of employment and livelihood. Generally, the tribals migrate to the places such as Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Surat, Kerala, Goa and Bhopal. Fig. 1 refers to the destination of the migrants at the time of the study. Among the destination of the migrants 21.50 per cent of them have gone to places like Chennai and Bangalore (Tamil Nadu), then about 18 per cent to Kerala whereas 16.50 per cent to Goa. Around 15 per cent to Mumbai, whereas 13 per cent to Gujarat and the lowest to 3.50 per cent to Madhya Pradesh.

|

Figure 1: Destination of Tribal Migrants Click here to view Figure |

Distribution of Work at Destination

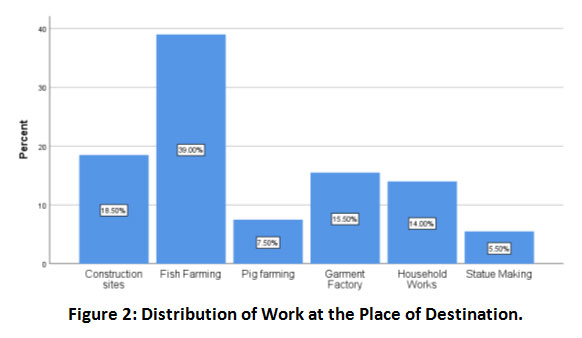

In search of employment, the migrants get to engage in all three sectors of the Indian economy, i.e., agriculture, industry and services full of opportunities. Fig. 2 indicates that maximum migrants work at the fish farming and fishing purposes, about 39 per cent, whereas construction labours at the destination place around 18.50 per cent. Almost 15.50 and 14 per cent of migrants work at factories and domestic works by the female migrants respectively. Domestic work including babies caretaker and household chores has prominently emerged as a new occupation for tribal girls, especially the young age group. Domestic workers are more vulnerable as compared to another different sort of workers since they are officially not categorized as a worker, hence are not covered by any laws applied to them. However, some civil society organizations had raised voice for the rights of domestic workers and have prevailed with regards to acquiring state government orders identifying minimum age, working hours as well as conditions and days per week. Along with the other working conditions the tribal migrants were engaged at pig farms (7.50%) and (5.50%) involved in statue making.

|

Figure 2: Distribution of Work at the Place of Destination. Click here to view Figure |

Perception about Migration

Duration of Migration

Table 4: Duration of Migration of the Respondents.

|

Sl. No. |

Duration |

Response of Migrants (Percentage) |

|

1 |

Long Term (1yr<) |

60 |

|

2 |

Short Term (0>1yr) |

29 |

|

3 |

Task Based |

1.5 |

|

4 |

Contract |

9.5 |

Table 4 implicates the duration of migration of the tribal population, though displaced from their original habitats and the following reasons leading towards enforced migration working as migrant labourers in construction sites, industry and domestic workers in cities and megacities. Labour migration flows include permanent, semi-permanent, and seasonal or circular migrants.50 Currently, one of every two tribal households relies on manual labour for survival, even in their home place or migrate to other states. Through the survey area, it was found that around 60 per cent of the migrants carry long term migration of one to three years, and short term from one year to six months or during the offseason, and 9.5 per cent move through contractual agreements. Lack of earning opportunities in local areas played a role of a magnet that attracts all the people from rural settings. As seen in scheduled areas, living conditions have degraded and rampant due to tough industrialization with no proper rehabilitation and accessibility to working advantages, these tribals feel to search for new jobs in other cities and megacities. Migrating through variant sources and channels, visit their destination, by the assistance of the contractors, migrant co-workers, friends and relatives, unknown from its consequences of exploitation and vulnerability to the working conditions at the workplace. The contract labour system and loose monitoring and regulating state apparatus have gradually co-operated and strengthened these unfair models and practices appearing in the migrant job market.51

Reasons for Migration

Table 5: Various Reasons of the Respondents for Migration.

|

Sl. No. |

Reasons |

Male + Female (Percentage) |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

||

|

1 |

Poverty |

99.5 |

0.5% |

00 |

00 |

|

2 |

Family needs better fulfilled through migration |

93.5 |

6.5 |

00 |

00 |

|

3 |

Displacement |

36 |

27.5 |

36.5 |

00 |

|

4 |

Natural calamities |

7.5 |

3 |

89.5 |

00 |

|

5 |

Debt |

6 |

55 |

39 |

00 |

Migration in India illustrates a historical account that shows people’s mobility from their origins to a different occupation, due to environmental changes, construction of development projects and natural calamities. Poverty, unemployment and inaccessibility to resources are seen to be the prime factors for migration among the tribals from rural to urban areas, with a clue to have a better life. The improved technological revolution in industrialization, communications and transport networks has created new economic strategies and thereby raised the level of mobility and need of the labour market. Table 5 indicates that about 99.5 per cent of the respondent households strongly agree on poverty as the paramount reason to move for better opportunities. Whereas 93.5 per cent strongly viewed their migration carrying the essential needs of their families like re-building their houses, education for their children, buying agriculture land and cattle too, etc.

Work Place Facilities

Table 6: Facilities Provided to the Tribal Migrants at their Respective Work Place.

|

Sl. No. |

Work place facilities |

Male + Female (Percentage) |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

||

|

1 |

Bonus |

00 |

2 |

93 |

5 |

|

2 |

Medical Allowance |

00 |

00 |

99 |

1 |

|

3 |

Transport Allowance |

00 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

|

4 |

House Rent Allowance |

00 |

4 |

96 |

00 |

|

5 |

First Aid |

00 |

21.5 |

78.5 |

00 |

“The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment & Conditions of Service) Act, 1996 and other related Acts mandate the registration of the workers as beneficiaries in Building and Other Construction Welfare Boards. It entitles workers welfare, safety, health insurance and other beneficial measures and stipulates the number of permissible hours of work, conditions of work, guidelines for payment of wages and compensation packages in the event of accidents, etc. Under the Act, both Central and State Advisory Committees are directed to be formed by the Central and State Governments respectively. Contravention of safety and health-related provisions for employers is punishable with imprisonment and/or fine.”52 A study conducted by ILO reveals that India has the highest accident rate on the job among construction workers worldwide with 165 out of every 1000 workers.53 In such an unorganised labour market the labour face regular conflicts and disputes like non-payment of wages, physical injuries, and unconditional death. These migrants are irrespectively down towards all access to various government schemes regarding subsidised food, health care and other allowances. The study area collected a poor response from the respondents regarding the provisions and allowances to be provided to the migrants, because they are informally employed in their workplaces. As indicated in Table 6, nearly 93 per cent declared about the absence of bonus, 99 per cent disagreed with medical facilities, during the time of injuries and accident, 100 per cent and 96 per cent disagreed with transport and House Rent allowances to be provided respectively. Overall in concern to the construction workers, no such facilities or social security neither compensation nor health care is provided.

Awareness about Political Rights

Table 7: Awareness of Tribal Migrants about their Political Rights.

|

Sl. No. |

Political Rights |

Male + Female (Percentage) |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

||

|

1 |

Freedom of thoughts and Expression |

00 |

00 |

81 |

19 |

|

2 |

Sharing Ideas |

00 |

7.5 |

92.5 |

00 |

|

3 |

Labour Rights |

00 |

16.5 |

83.5 |

00 |

|

4 |

Right to Vote |

00 |

97 |

00 |

3 |

|

5 |

Do you go to cast your vote during elections |

00 |

7.5 |

92.5 |

00 |

|

6 |

Participation in Decision Making |

00 |

00 |

100 |

00 |

The study even included the views of the migrants referred to the Political Rights, where the respondents delivered their ideas through Agree, Disagree and Neutral. As displayed in table 7, it is examined and found that 100 per cent of respondent migrants have no role in the platform of the Decision-making process, as well as 92.5 per cent of migrants, confessed that their ideas are never heard. There is a suggestion box in the companies where they work, to put their complaints and suggestions regarding the work process, but it is unheard and unseen. Further 97 per cent of the migrants are aware of their voting rights, but during the election time, only 7.5 per cent of migrants agreed that they are allowed or granted leave to go to their places, to cast their votes, whereas 92.5 per cent lose their rights. Thereby political elites ignore them as they are never counted as voters, especially in interstate migration. Additionally, the migrants are not a permanent employee and constantly move from cities to new companies so they don’t have any recommendation in the declaration of the trade unions. Multi-storied malls, market complex and developed cities are constructed on the hard labour of the exploited migrants, but they have never entered the mainstream of development. After the hardship of the whole day, they silently return to their abode, may be rented room gathered by 10-12 members, open sites with poor water and electricity facilities and drainage system, or at the worksites, vulnerable to security and hygiene.

Plan for Future

Table 8: Future Plan of Tribal Migrants and Livelihood Process.

|

Sl. No. |

Plan for future |

Male + Female (Percentage) |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

||

|

1 |

Do you think migration is better solution to your problems |

1.5 |

2.5 |

84 |

12 |

|

2 |

would you like to return to your village to live |

87.5 |

5.5 |

7 |

00 |

|

3 |

Would you like to go outside India for work, if you get any such opportunity? |

00 |

1 |

93 |

6 |

Table 8 shows the agitation the migrants carry while they are far away from their land and families. It has been observed that 87.5 per cent of the tribal migrants have a true gesture to return to the village and about 84 per cent indicated that migrating to such an unknown destination is truly difficult to survive, if though they have job opportunities at their places, they will never opt to fly away from their habitat. These migrant workers are temporarily and flexibly situated at their worksites, with a poor payment and can be anytime fired, whereas 7 per cent have no desire to be back as they have lost their hopes from the government. Further 93 per cent of them reported that they have no interest to migrate outside India because they are aware of the migrants' condition and even they have to fear their disability regarding their language and culture disparities.

Future Plan of Earned Money

Table 9: Response of Tribal Migrants Regarding Utilization of the Earned Money.

|

Sl. No. |

Future plan of earned money |

Male + Female (Percentage) |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

||

|

1 |

Support yourself |

100 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

|

2 |

Support family

|

58.5

|

41.5 |

00 |

00 |

|

3 |

Marriage expense |

19.5 |

33.5 |

47 |

00 |

|

4 |

Buy land |

00 |

28 |

72 |

00 |

|

5 |

Build a new house |

5.5 |

61.5

|

26 |

7 |

|

6 |

Buy home appliances |

28 |

46 |

13.5 |

12.5 |

|

7 |

Education of children |

52 |

33.5 |

14.5 |

00 |

Tribal migrants are poorly endowed all through their existence vulnerable and poor to access standard living, financially poor and incapable of have improved and purposive living due to their inferiority and low communicative skills. Unfortunately, the state response continues to be poor with a low scale of perusing the migrants ensuring to provide an able life. Table 9 reflects that 100 per cent of the migrated people want to have their survival instinct and fore mostly develop them so that they can support their family too strongly. The tribal migrants too have a consciousness to educate their children were 52 per cent strongly agreed and 33.5 per cent agreed that their saving will be invested in their children education. They are aware, regarding the need for proper education because, lack of education will spoil their children lives and they may be enforced to expose themselves to such hazardous places, with an invisible future.

Women Headed Households

Table 10: Response of Women Headed Households on Maintaining Socio-Economic Prospects.

|

Sl.No. |

Headed Households |

Female (Percentage) |

||||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Total |

||

|

1 |

Do you experience a changed life after the migration of your family members |

22.5 |

67.5 |

00 |

10 |

40 |

|

2 |

Do you think migration has brought a change in the economic condition |

30 |

52.5 |

17.5 |

00 |

40 |

|

3 |

Do you face problem in management and investment remittances |

10 |

77.5 |

12.5 |

00 |

40 |

|

4 |

Do migration gives opportunities to learn about the outer society and build network |

00 |

20 |

80 |

00 |

40 |

|

5. |

Do you think people should not migrate |

00 |

62.5 |

30 |

7.5 |

40 |

Migration upholds the issues not only relating to the migrants but also brings consequences to their family members left behind. Tribal migrants migrate without their family, leaving back their old parents, wife and children, responsibility heads upon the women headed to manage the family, as it becomes difficult for them. Cases are often reported regarding the non-accessibility of migrants’ family to the various welfare schemes of the government and their association with the market, local administration and Panchayat in the absence of the male head of the household. Women from the migrant households, with their revised gender roles, endure double the workload and suffer the regular loss of entitlements54 as replied by 77.5 per cent of the women-headed households indicated in table 10. The research study further reveals the situation faced by the household head, around 67.5 per cent feel there is a change in their living and 52.5 per cent agreed on a minimum lift in their economic condition, whereas 62.5 per cent think migration is not an appropriate decision to rebuild their broken world.

Case Study and Findings

The regularity of migration in Odisha can be induced both on distress condition and opportunity-driven for attracting to address a new destination as the portability of socio-economic and democratic rights been concerned. Migration is not a mere shift of people from one’s habitant to a new destination. Such change in place and space and confirming a relationship in a new area is quite absolute due to the unfortunate condition raised as per interruption.55 Movement of people from one place to another for more opportunities drag them towards urban settings because small land holding, low income, low living standard, less agricultural productivity compels them to migrate to such diversification of the economy. Simultaneously, the urban localities get over-crowded and create other issues, so the government must look down on providing better preferences at the rural level so that the human flow may be minimised. Overall, the study reflects that there is an increase of jobs in the informal sector that has duly convinced the marginalised and vulnerable communities of the society, for improved life and better sustainable options shared. Especially in the developing countries, the ample number of job benefits acknowledge with, low skill and low productivity, no guarantee to social security or legal protection and providing poor working conditions. Further unparallel policy intact, poor investment in rural tribal areas has pushed them as migrants in the unorganized sector, and even they remain outside the government services and social privileges.

As the study is intensive fieldwork, sharing the stories of the tribal migrants will show their troubled living and work hazards. The experience of Binod Kharia, married aged 32 years, from Rajgangpur block, migrated to Goa, leaving behind old parents, his wife and two children. His ancestral land proved to be poor crop yielding due to no proper irrigation facilities and low fertile land, availing migration seemed to be the better option for survival. Unaware of the consequences, resting his fate on his friends’ assurance moved to an unveiled place. He earned some money but risking his life with no benefits, or preservation for his future.

Another tribal migrant, Kumud Majhi, resident of Sudega block, married, age 28 years, eldest son of his family signed a contract with the verbal assurance for a better job opportunity moved with some other migrants to Chennai, to test his destiny. A verbal agreement was made to provide a job at an automobile factory as he was an experienced semi-skilled worker. As he reached his destination, he has to work as unskilled labour for two years without any progress neither in his salary nor position. He had dreams to support his family and save some money for his coming future but returned home with an empty heart and pocket, and presently cultivating his ancestral land and depending on forest products.

Pusha Munda, a 39 years old man migrated to Gujurat through a local contract to get engaged in a cloth factory, leaving behind his wife, a mother of three children, one sister and old parents. Unfortunately, he died at his workplace. His family was informed immediately and his body was somehow brought back to his family, but no compensation amount was paid to his family. Pusha's case is a burning instance of Violation of Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970, the Factories Act, 1948 and the Workmen's Compensation Act, 1923. These different legal provisions guarantee social security to the workers as well as compensation of a minimum of Rs. 80,000/- in case of death and a minimum of Rs 90,000 in the event of permanent total disabilities arose while working in their workplace. Moreover, the Employees State Insurance Act, 1948 also provides for certain benefits for workers in case of employment injury, sickness and maternity. But, on other hand, the family members of this tribal migrant were unaware of these provisions and remained silent because of their illiteracy and simplicity texture acknowledging their fate. Presently the widow of Sukram is working as a daily labourer in her neighbourhood, as well in her small piece of land cultivating seasonal crops and gathering food products from forest and looking after her family.

Another incident too happened in the neighbouring village, where the migrant, named Mangla Burh, age 38, went to Chennai 3 years back, to work in a factory encountered with a sudden incident that took place at his working time with a machine, when four of his fingers got crushed and a possibly due to critical condition his arm has to cut off by surgical operation, within a blink whole of his life got devastated. The incident took place because the worker was unaware of the functioning of the machine and had zero knowledge about the safety operations. The employer-provided small monetary assistance that recompenses his medical expenditure. Now he was of no profit to the employer, and so after his release from the hospital, he was advised to rest, remained idle without pay, it troubled him and thereby decided to be back to his family in the village. A grace amount of Rs 40,000 was paid to him to reimburse his travelling expenses and to stay in his village, helplessly and disappointed.

Sukanti Kisan, a young girl of 18 years, after her schooling, through a middle man migrated to Delhi, with her other friends to work in domestic areas. To fight poverty and feed her family and 2 younger brothers still in school dreamed of better education and future for them moved to an unknown land. At present, she has returned to her village and working at a construction site as a daily labourer, nearby place. During the interview, with tears in her eyes, she narrated her pathetic stay in her previous working place. She used to stay, with the owner and worked hours beyond with a promise to be paid Rs. 5000 per month, but only Rs 2000 she was paid. Harassment, abuse, torture and mental distress were common to her, she was not allowed to use the phone to call her parents, and after such pain, she decided to run away. By the help of one of her friend staying at the neighbourhood, booked the train ticket and a small chance held her to fly away from her destination prison.

For Biranchi Munda, of Kuarmunda block 49 years old father of 21 years old Kishore, who left his education in between without informing his family decide to run away to Mumbai, with other teenagers and young adults through a contractor, to provide a good job and stay in the city. After a few months, along with other migrants, Kishore too boards the train to return to his village because at the construction sites the work was too dangerous and risky to live. But on the way home, he was lost from the group and was never found again. The father of this young man is still in pain of his lost son because they are blank about his existence or death, such loss is unbearable for the family. He determines strongly that he will never allow his other two sons and a daughter to migrate, whatever they earn they can survive, he assures himself.

Migration not only aspire the migrants but also the family members who are left behind, with no proper source of remuneration, face the consequences, who rely on their agriculture outcome, selling of cattle and BPL card. Rita Topno, age 35, two sons, wife of Bishu Topno, of Balisankara block, narrates her story when her husband is far for in Goa working on a fishing farm, to earn money which will help them to cultivate their agricultural land and rebuild their thatched house, which drifts during the rainy season. She delineates, that family depends on the remittances send by his husband, as she is not well educated (Studied till Class 2) and so unaware of government policies and programmes. So, to get some subsistence from the government she is assisted by her neighbours, and with all difficulty, she is managing her family.

Conclusion

Migration has its hidden imposition on the lives of the migrants both positively and negatively. For an educated and well trained and capable individual moving to a new destination helps him to explore and rapidly accumulate capital for a better livelihood. But for a marginalized and vulnerable poor tribal migrant, the positivity of earning money no way help him accumulate for his better future who historically belong to an oppressed community exploited and suppressed. Through the case studies, it shows the extreme difficulty and high risk, faced by the migrants both mentally and physically because of their un-identification faults as migrant labourers and unaware of the labour laws and their implications. Lack of adequate job opportunities, lack of protection of tribal basic rights to livelihood, improper regulation of rehabilitation and recommendation of benefits in industrialization in tribal areas, illiteracy, ignorance and vulnerable capacity of living standard engulf themselves forcibly in the way towards the migration. Both secondary and primary data emphasis migration as a source to beat poverty, but human rights violation is intolerable among the migrants. The immediate need monitor the policy level discourse on migration and recognizing the need of these vulnerable tribal communities, like proper access to education, provided land and forest rights and proper functioning of the policies in tribal belts to control such human flow towards distressed living. Collective recognition of the government, grassroots administration and cooperation of civil society is needed for community orientation and dispense justice.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Roshan Ekka, Stephen John Ekka, and Sanjeet Minz for their extensive assistance to reach to the tribals dwelling even in the most remote places of the study area.

Funding Source

The research paper is a part of Major Research Project sponsored by Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), Government of India (F.No. 02/92/ST/2017-18/RP/Major Dated: 29-12-2017).

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of Interest

References

- Sainath, P. (2011, Sep 26). Decadal journeys: Debt and Despair spur urban growth. The Hindu. Retrieved from http//:thehindu.com/opinion/columns/sainath/decadal-journeys-debtanddespair-spur-urbangruwth/article2487670.ece

- World Economic Forum. (2017). Migration and its Impact on cities. p.10 Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Migration_Impact_Cities_report_2017_HR.pdf; Chandra, J., Paswan, B. (2020). Perception about migration among Oraon Tribes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(2), 616-622. p.1 doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.013S

CrossRef - Mosse, D. (2005). Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London: Pluto Press. p.72 doi: 10.2307/j.ctt18fs4st

CrossRef - Gardner, K., Osella, F. (2003). Migration, Modernity and Social Transformation in South Asia: An Overview. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 37(1-2), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670303700101; Mosse, D., et al. (2005). On the Margins in the City: Adivasi Seasonal Labour Migration in Western India. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(28), 3025-3038. p. 3026 Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/4416873; Choudhary, N., Parthasarathy, D. (2009). Is Migration Status A Determinant Of Urban Nutrition Insecurity? Empirical Evidence From Mumbai City. India. Journal Of Biosocial Science, 41(5), 583-605. p.583 doi: 10.1017/S002193200900340x

CrossRef - Mosse, D., et al. (2005). On the Margins in the City: Adivasi Seasonal Labour Migration in Western India. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(28), 3025-3038. p. 3026 Retrieved Nov 26, 2019, from www.jstor.org/stable/4416873; Choudhary, N., Parthasarathy, D. (2009). Is Migration Status A Determinant Of Urban Nutrition Insecurity? Empirical Evidence From Mumbai City. India. Journal Of Biosocial Science, 41(5), 583-605. p.583 doi: 10.1017/S002193200900340x

CrossRef - Yadav, N. (2018). Migration and labour economic concerns Analyse major factors contributing to the migration of workers into construction industry: A case study of contractual workers and casual/daily-wage workers. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences 8 (6(1)), 488-95. p.490 Retrieved from https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2018/IJRSS_JUNE2018/IJRSSJune.pdf?cv=1

- Government of India. (2018). Migration of Tribals. Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1556176

- Singh, V., Jha, K. (2004). Migration of Tribal Women from Jharkhand: The Price of Development. Indian Anthropologist, 34(2), 69-78. p.74 Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41919966

- Giri, J., et al. (2009). Migration in Koraput: “In Search of a Less Grim Set of Possibilities” A Study in Four Blocks of tribal-dominated Koraput District, Orissa. Society for Promoting Rural Education and Development, Orissa. p.1 Retrieved from https://www.spread.org.in/document/Migration_Report.pdf?cv=1

- Bansal, S. (2016, Dec 2). 45 Crore Indians are internal Migrants. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/data/45.36-crore-Indians-are-internal-migrants/article16748716.ece#:~:text=45.36%20crore%20Indians%20(37%20per,per%20cent%2C%20migrate%20for%20marriage

- Pranav, D. (2018). India preparing for the biggest human migration on the planet. Invest India, National Investment Promotion & Facilitation Agency, Government of India. Retrieved from https://www.investindia.gov.in/team-india-blogs/india-preparing-biggest-human-migration-planet

- Gulankar., A. (2019, June 21). Number of People in India's Cities Will Overtake Rural Population in Next Three Decades. News18 India. Retrieved from https://www.news18.com/news/india/number-of-people-in-indias-cities-will-overtake-rural-population-by-2050-says-report-2197025.html

- FAO. (2016). Migration, Agriculture and Rural Development. Food and Agriculture Organisation, United Nations. p.3 Retrieved Jan 28, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6064e.pdf; Chandra, J., Paswan, B. (2020). Perception about migration among Oraon Tribes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8 (2), 616-622. p.617 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.013

CrossRef - Chandra, J., Paswan, B. (2020). Perception about migration among Oraon Tribes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8 (2), 616-622. p.617 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.013

CrossRef - Lee, E. (1966). A Theory of Migration. Demography, 3(1), 47-57. Retrieved Feb 12, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/2060063

CrossRef - Harrison, B., Sum, A. (1979). The Theory of "Dual" or Segmented Labor Markets. Journal of Economic Issues, 13(3), 687-706. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/4224841

CrossRef - Sorinel, C. (2010) Immanuel Wallerstein's World System Theory. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 1(2), 220-224. Retrieved from https://econpapers.repec.org/article/orajournl/v_3a1_3ay_3a2010_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a220-224.htm

- Ravenstein, E. (1885). The Laws of Migration. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 48(2), 167-235. doi: 10.2307/2979181

CrossRef - Schlogl, L., Sumner, A. (2020). Economic Development and Structural Transformation. In: Schlogl, L. & Sumner, A. (Eds.), Disrupted Development and the Future of Inequality in the Age of Automation (pp.11-20). Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30131-6_2

CrossRef - Bhagat, R.B. (2011). Internal Migration in India: Are the Underclass more Mobile?. In: Rajan, S.I., (Eds.) Migration, Identity and Conflict: India Migration Report 2011 (pp.7-24). New Delhi: Routledge. p.22

- Mosse, D., et al. (2002). Brokered livelihoods: Debt, Labour Migration and Development in Tribal Western India. The Journal of Development Studies, 38(5), 59-88. doi: 10.1080/00220380412331322511

CrossRef - Jha, V. (2005). Migration of Orissa’s Tribal Women: A New Story of Exploitation. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(15), 495-96.

- Veerabhadrudu, B., Subramanyam, V. (2013). Displacement, migration and occupational change among the project displaced tribal communities in India: A study of Peddagadda reservoir. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 14(3), 26-35. doi: 10.9790/1959-1432635

CrossRef - Chandra, J., Paswan, B. (2020). Perception about migration among Oraon Tribes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(2), 616-622. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.013

CrossRef - Patel, A., & Giri, J. (2019). Climate Change, Migration and Women: Analysing Construction Workers in Odisha. Social Change, 49(1), 97–113. doi:10.1177/0049085718821756

CrossRef - Government of Odisha. (2020a). About Odisha. Odisha Tourism. Retrieved from https://www.nuaodisha.com/aboutodisha.aspx

- Pradhan, A. C. (2013). The New Capital at Bhubaneswar. Orissa Review, 69(9), 55-59. p.56 Retrieved from http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2013/apr/engpdf/april-or-2013.pdf

- Government of India. (2011). Provisional Population Totals Orissa. Census of India 2011, Series 22, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. p.1 Retrieved from https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/orissa/Provisional%20Population%20Total%20Orissa-Book.pdf

- Government of Odisha. (2020b). About the Department. ST & SC Development, Minorities & Backward Classes Welfare Department. Retrieved from http://www.stscodisha.gov.in/Aboutus.asp?GL=abt&PL=1

- Sahoo, L. K. (2011). Socio-Economic Profile of Tribal Populations in Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar districts. Orissa Review, 68(10), 63-68. p. 63 Retrieved from http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2011/may/engpdf/may.pdf

- Government of India. (2013). Statistical Profile of Scheduled Tribes In India. Statistics Division, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. pp.1-3 Retrieved from https://tribal.nic.in/ST/StatisticalProfileofSTs2013.pdf

- Hans, A. (2014). Scheduled Tribe Women of Odisha. Odisha Review, 71(4), 26-39. p.26 Retrieved from http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2014/Nov/engpdf/november-or-2014.pdf

- Government of Odisha. (2016). Odisha District Gazetteers Sundargarh. General Administration Department. p.310 Retrieved from https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s3289dff07669d7a23de0ef88d2f7129e7/uploads/2018/05/2018051651.pdf

- Government of Odisha. (2014). District Census Handbook Sundargarh. Census of India 2011, Series-22, Part Xii-B, Directorate of Census Operations, Odisha. pp.17-18 Retrieved from https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s3289dff07669d7a23de0ef88d2f7129e7/uploads/2018/05/2018051448.pdf

- Government of Odisha. (2016). Odisha District Gazetteers Sundargarh. General Administration Department. p.16 Retrieved from https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s3289dff07669d7a23de0ef88d2f7129e7/uploads/2018/05/2018051651.pdf

- Parida, S. P. (2008). Tribal Poverty in Rural Odisha. The Tribal Tribune, 3(3). Retrieved from https://www.etribaltribune.com/index.php/volume-3/mv3i3/tribal-poverty-in-rural-odisha

- Mehta, S. K. (2011). Including Scheduled Tribes in Orissa’s Development: Barriers and Opportunities. UNICEF Working Paper Series, Institute for Human Development, India. p.13 Retrieved from http://www.ihdindia.org/pdf/IHD-UNICEF-WP-09_saumya_kapoor.pdf; Rout, N. (2015). Tribal Land Conflicts And State Forestry In Odisha: A Historical Study. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management, 2(2), 143-147. p. 146 doi: 10.3126/ijssm.v2i2.12423

CrossRef - Ibid

- Mehta, S. K. (2011). Including Scheduled Tribes in Orissa’s Development: Barriers and Opportunities. UNICEF Working Paper Series, Institute for Human Development, India. p.1 Retrieved from http://www.ihdindia.org/pdf/IHD-UNICEF-WP-09_saumya_kapoor.pdf

- Government of India. (2018). Migration of Tribals. Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1556176

- Government of India. (2014). Tribal Profile at a Glance. Ministry of Tribal Affairs. p.3 Retrieved from https://tribal.nic.in/ST/Tribal%20Profile.pdf

- Government of India. (2018). Migration of Tribals. Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1556176

- Government of India. (2014). Tribal Profile at a Glance. Ministry of Tribal Affairs. pp. 11,17 Retrieved from https://tribal.nic.in/ST/Tribal%20Profile.pdf

- Mosse, D., et al. (2002). Brokered livelihoods: Debt, Labour Migration and Development in Tribal Western India. The Journal of Development Studies, 38(5), 59-88. p. 66 doi: 10.1080/00220380412331322511; Mosse, D., et al. (2005). On the Margins in the City: Adivasi Seasonal Labour Migration in Western India. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(28), 3025-3038. p. 3026 Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/4416873

CrossRef - Government of Odisha. (2020c). Population and Literacy. ST & SC Development, Minorities & Backward Classes Welfare Department. Retrieved from http://www.stscodisha.gov.in/Population.asp?GL=abt&PL=5

- Government of India. (2001). Orissa Data Highlights: The Scheduled Tribes. Office of the Registrar General, India. p. 2 Retrieved from http://censusindia.gov.in/Tables_Published/SCST/dh_st_orissa.pdf

- Government of Odisha. (2020c). Population and Literacy. ST & SC Development, Minorities & Backward Classes Welfare Department. Retrieved from http://www.stscodisha.gov.in/Population.asp?GL=abt&PL=5

- Government of India. (2018). Migration of Tribals. Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1556176

- CMLS. (2014). Seasonal Labor Migration and Migrant Workers from Odisha. Aajeevika Bureau, Udaipur. p. 2 Retrieved from http://www.aajeevika.org/assets/pdfs/Odisha%20State%20Migration%20Profile%20Report.pdf?cv=1

- Dineshappa, S., Sreenivasa N.K. (2014). The social impacts of migration in India. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 3(5), 19–24. p.21 Retrieved from http://www.ijhssi.org/papers/v3(5)/Version-3/D0353019024.pdf; Chandra, J., Paswan, B. (2020). Perception about migration among Oraon Tribes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(2), 616-622. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.013 p.618

CrossRef - Sharma, K. (2017). India has 139 million internal migrants, They must not be forgotten. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/india-has-139-million-internal-migrants-we-must-not-forget-them/

- CMLS. (2014). Seasonal Labor Migration and Migrant Workers from Odisha. Aajeevika Bureau, Udaipur. p. 56 Retrieved from http://www.aajeevika.org/assets/pdfs/Odisha%20State%20Migration%20Profile%20Report.pdf?cv=1

- Sarde, S.R. (2008). Migration in India, Trade Union Perspective in the context of neoliberal globalisation. International metalworkers federation, New Delhi, Mimeo. p.3; Deshingkar, P., Akter, S. (2009). Migration and Human Development in India. Human Development Research Paper 2009/13, United Nations Development Programme. p. 9 Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19193/1/MPRA_paper_19193.pdf

- CMLS. (2014). Seasonal Labor Migration and Migrant Workers from Odisha. Aajeevika Bureau, Udaipur. p. 25 Retrieved from http://www.aajeevika.org/assets/pdfs/Odisha%20State%20Migration%20Profile%20Report.pdf?cv=1

- Shamshadi, (2017). The genesis of Houselessness in the Megapolises: A Case Study of Kanpur City. Canadian Journal of Tropical Geography, 4(2), 48-64. p. 52 Retrieved from https://www3.laurentian.ca/rcgt-cjtg/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Article_5_Dr.-Shamshad_vol_4_2_2017-2.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.