Ikam as the Social and Economic Heritage of the Bujuur Tribe

Elija Chara1  and NG Khosirngak Moyon2

and NG Khosirngak Moyon2

1Department of Sociology, Highland National College, Manipur, India .

2Department of Education, South East Manipur College, Manipur, India .

Ikam, or Feast of Wealth, is one of the most important traditional events for the Bujuur community of Chandel and Tengnoupal Hills of Manipur State in India. Traditionally held during the spring season by wealthy individuals following bumper harvests, Ikam was significant for the Bujuur not just as an event of merry-making but a space to display the unique Bujuur customs. Celebrated for hundreds of years and part of the social history-identity, Ikam abruptly disappeared after the year 1946 as a result of the paradigm shift in religion, social lifestyle and economic outlooks. The legacy of Ikam can be witnessed from many Rutha (megaliths) erected in historical Bujuur villages. This article explores the cultural heritage of the Bujuur with specific reference to Ikam through the comprehensive description of the Ikam events including its various components, unique features and megaliths attributed to it. In addition, the paper also discusses the relationship between Ikam, agriculture and customs with the objective of relooking the Bujuur socio-economic heritage.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Chara E, Moyon N. G. K. Ikam as the Social and Economic Heritage of the Bujuur Tribe. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2024 7(1).

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Chara E, Moyon N. G. K. Ikam as the Social and Economic Heritage of the Bujuur Tribe. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2024 7(1). Available here: https://bit.ly/49eG0QE

Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 01-12-2023 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 10-01-2024 | |

| Reviewed by: |

Meenu Sharma

Meenu Sharma

|

|

| Second Review by: |

Bayram Quliyev

Bayram Quliyev

|

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Yatindra Singh Sisodia | |

Introduction

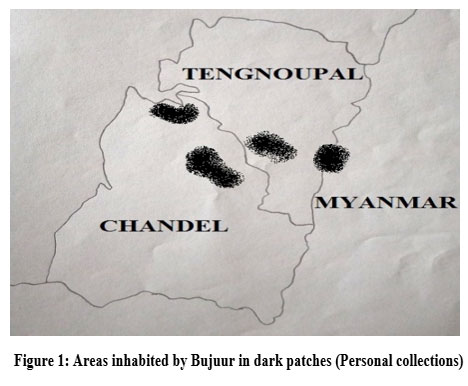

Bujuur, commonly known by their official and exonym Moyon Naga, is one of the many ethnic groups that constitute the Naga. The population of the tribe is about 3000 and scattered in Chandel and Tengnoupal districts of Manipur in India and in Sagaing region of Myanmar. (Chara, 2021) (Bujuur Aanchung Puh, 2021) 1Some of the important Bujuur villages in India are Kapaam, Nungthar, Tungphae, Khungjuur, Matung, Bujuur Khufhuw and Mengkang; among the villages, Kapaam is the largest with a population of about 1000. There is also one Bujuur village in Myanmar by the name Napulun. (Golden Jubilee Souvenir, 2007) The Bujuur consisted of three cultural-geographical groups: Khufhuw- Bujuur of Bujuur Khufhuw, Khunee- Bujuur who had migrated to the west from Bujuur Khufhuw and Duung- Bujuur who lived in the Kabaw Valley of Myanmar.

|

Figure 1: Areas inhabited by Bujuur in dark patches (Personal collections). Click here to view Figure |

Traditionally, Bujuur celebrated the following festivals- Paam Lachii Ishaen, Shachü-Ithah(seed sowing), Shangken (paddy ritual), Shangthen (paddy ritual), Ruwfhuw Yngkhap/ Buwrenpeh (first cutting of paddy/beginning of harvest), Vaangcheh (last cutting of job’s tears/end of harvest) and Meedim (Festival of Fire and New year). These traditional festivals were simple rituals participated only a few like the villageIthüm (shaman priest), Khuwfhuw (priest) and selected individuals.(Shangkham, 1995) If there were wealthy individuals in the village, then some traditional festivals like Shangthen, Vaangcheh and Meedim could be accompanied by feasts and merry-making. These patrons of such feasts and marry-making were either wealthy individuals or individuals who had extraordinary achievements like having killed a tiger or hosted a feast of merits. Feasts of merits were important traditional events of the Bujuur where the rich wealthy individuals hosted grand feasts and merry-making lasting for days.

‘Traditionally, there were three feasts of merit,

Among the three feasts of merits, Ikam was regarded by the Bujuur as the most prestigious commanding respect for the individuals hosting the event – the respect was accorded both while alive and after death. Lashum Bathen(also known as Jaaka Itheeng) was usually held on the evenings of Shangthen, Vaangcheh and Meedim after an archery competition known as Ber Ikaap. Thiir Iphin was a rare event, usually done by men in the later stages of their lives as a symbolic display of their achievements. It involved the erection of a monolith, known as Thiir, symbolising the achievements of the individual.

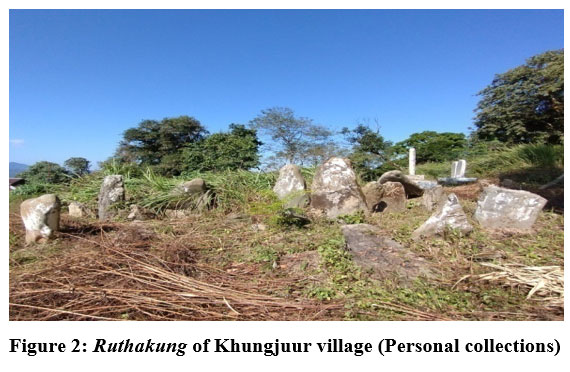

The three feasts of merits are no longer celebrated by the Bujuur as a result of a paradigm shift in their religion, traditions, occupations and outlook of life as a result of their conversion to Christianity and exposure to westernisation starting in the year 1922. The testimonies of these feasts of merits however stand till today in the form of rutha (megaliths) in historical villages like Khungjuur, Matung and Bujuur Khuwfhuw (see Figure 2). Similarly, the Bujuur folk songs sung today are also the legacies of those feasts as many of the folk songs revolve around the feasts or were composed for the feasts of merits. The contemporary Bujuur folk dance known as Moyon Cultural Dance or Bujuur Kastam Ilam is also remade of the traditional dance performed during Ikam or Lashum Bathen.

|

Figure 2: Ruthakung of Khungjuur village (Personal collections) Click here to view Figure |

Materials and Methods

The article is an outcome of exploratory research among the Bujuur tribe of Chandel District, Manipur in India. The research explored the traditional festivals of the Bujuur tribe with specific reference to Ikam with the goal of understanding traditional events that are no longer celebrated by the people and then building upon the social-economic heritage of the tribe through the lens of Ikam. In the course of the research, primary data from the field via field visits, interviews and discussions, group discussions and personal stories play key roles in the streamlining and analysis of the data. For the field visit, Khungjuur village was the main focal point of the study as many of the Ikam narratives and surviving artefacts are from the village. The elderly population who have had personal experiences of the Ikam and individuals whose ancestors had hosted Ikam were also primary participants in the interviews and discussions. In addition, local writings in the form of self-published books on the history, culture and literature of the Bujuur are also consulted to strengthen the field data; secondary data is very crucial in the research of Ikam as the number of individuals with knowledge on Ikam and the associated heritage is very less and, thus, the available local writings substantiate to the data loopholes of the field. The multitudes of data from the research, after undergoing compilation and analysis, are presented descriptively into the following themes: components of the Ikam (Ikam: The Feast and Festival), Bujuur social-economy of the past (Ikam and Bujuur socio-economic heritage) and an analytical discussion at the end on the contemporary issues with the attempts to preserve Ikam heritage.

Ikam: The Feast and Festival

Traditionally, Ikam was celebrated during the spring months of March and April. The event consisted of three days and nights, divided into Eenlun (first day), Zuwrshik (second day) and Kuurchiim (third day). On the day of Eenlum, the Kampa (the host)received the guests and there was a housewarming ritual to ward off evil spirits and for invoking blessings. The sisters of the Ikampa brought gifts in the form of a basketful of sticky rice, meat and rice beer to honour his generosity and kindness. (Ringhow, 1998) The guests were entertained with rice beers, meals and meat, followed by singing and dancing inside the house of the Ikampa. Zuwrshikwas reserved for the main dance ritual known as Kungkung Ilam, Khorom Ilam (public dance) and Zuwr-Imah Ilam for the sisters of the host and his brothers-in-law. Young and unmarried women sang and danced at night as well as they were in charge of the food and drinks. (Ringhow, 1998) The merry-making in the forms of songs and dances continued till the evening of Kuurchiim, the third day. To signal the end of the festive event, a cleansing ceremony known as Khurong Ithakwas performed. ‘The Ithüm or shaman, accompanied by singing and dancing crowds took a basket containing waste and leftovers to the western end of the village. At the village gate, the people were sent back, while the Ithüm proceeded to throw the basket in a secluded place.’(Ledeen, 2017) The purpose of the ceremony was to keep spirits away from the village by giving them the leftovers from the Ikam. It was believed that if such offerings were not made to the spirits, they would enter the village in search of food which would in turn cause sickness to the people. A village taboo known as Isher was also observed the next day by closing the village gate.

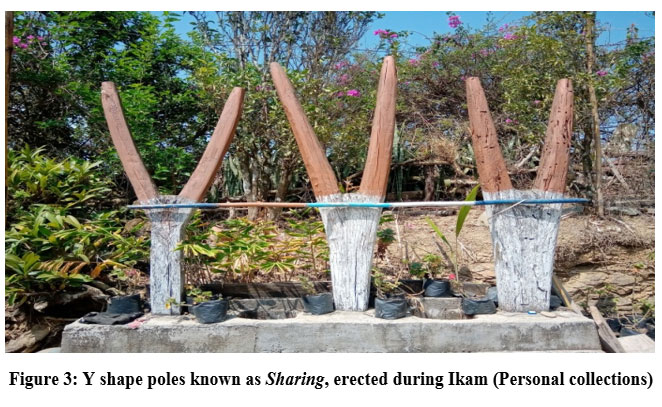

One of the main components of Ikam was the performance of the ritual Kungkung dance (or the main Ikam dance) on the morning of Zuwrshik. Kungkung was basically a dance troupe led by a man wearing Changkak Inih (a woman’s traditional attire) and carrying a spear.(Moshing, 2012) The kungkung danced three times around ashabaken (Bos frontalis) tied to a Y -shaped pole known as Sharing(See Figure 3). After the dance, an appointedIthüm (shaman) chanted prayers (known as Dee Ishuur) by throwing pieces of ae (wild turmeric) to seek blessings and forgiveness from the shabaken. The man in the woman’s dress invoked prayers (by shouting) and speared the shabaken. The speared animal was for the Ikam feast, symbolising Kthe Kampa sharing his wealth with the people. The other component of Ikam was the erection of sharing, which is a unique feature of the Bujuur tribe’s feast of merits. Sharing is a Y-shaped totem and ritual pole carved from the Iraang tree; it symbolised the merit of the Ikampa.

|

Figure 3: Y shape poles known as Sharing, erected during Ikam (Personal collections) Click here to view Figure |

The above descriptions constituted Ikam traditions in general. However, the unique feature of the Bujuur Ikam celebration is the hierarchical stages. The eight hierarchies of Ikam are - Eenzuw, Marzuw, Habae, Niing, Madeen, Pham Ituk, Rushong Shangka and Aesii-teen. The eight hierarchical stages corresponded to the number of times Ikam were hosted: if an Ikam was held for the first time, it was considered as the first stage (Eenzuw); if held the second time, it was known as (Marzuw) and so forth. The first three stages were known as inferior Ikam; they did not bring extraordinary merit and could be skipped under special circumstances. The other five Ikam were known as superior Ikam and they bring special merit, recognition and social position.‘Individuals hostingIkam at least till the fourth stage were honoured with Ikam dance at their funerals and a memorial stone known as rutha was also erected for them at the village gate on the occasion of Bar-Ynthee (a ritual performed a year after death).(Shangkham, 1995) However, for the Ikamnuw, a simple wooden plank was erected, which somehow symbolised that women were not conferred the merit as their husbands even though they contributed equally to the family wealth.

Each Ikam stage is unique and is briefly described as follows.

It is the feast to honour the eenkuw (near relatives and clan). It is usually a village--level merry-level merry-making with no extravaganza. A simple pole is also erected, but the pole is not Y-shaped.

Marzuw

Marzuw means ‘offering of zuw to the mar (friends)’. (Danichung, 2023) On the occasion, friends and well-wishers are honoured with feasts and merry-making. A Y -shaped pole known as sharing is erected.

Habae

The event is the same as the first two, but it is grander. At least two Y -shaped wooden poles are erected.

Niing

It is the first of the superior Ikam. It is held for three days and nights. The unique feature of this feast is the ceremony known as Buwtaang Ynjeh. Buwtaang special is specially cooked rice for the event mixed with herbs and meat. The Ikampa with his sons-in-law carry the buwtaang in baskets and cast at the people. Buwtaang symbolised the wealth of the Ikampa and the casting (Ynjeh) symbolised the sharing of wealth with the people. Three Shares are erected, but it could be more depending on the number of livestock slaughtered so far (including the livestock slaughtered at the previous Ikam). Men who hosted Ikam till this stage are honoured with Ikam dance at their funerals and a rutha (memorial stone) is also erected at the village gate.

Madeen

Madeen means “onward and wealthy”, signifying the wealth of the individual to pave a prosperous future. The rituals and merry-making events are similar to the first three Ikam. ‘Unlike the previous Ikam’s Kungkung ritual dance, the Kungkung ritual dance of Madeen is held in the evening and around the village. The unique feature of this Ikam is the pharchuumpa dance. A phaarchuumpa is a large umbrella presented to the Ikampa. The Ikampa holding a pharchuumpa is carried on a palanquin and taken for a procession around the village accompanied by people singing and dancing. The procession symbolised the wealth of the Ikampa’s reaching every house. If the dance procession encountered a house with Sharing, homage is also paid to the Sharing and owner of the house with a Kungkung ritual dance.’ (Ringhow, 1998)

Since Ikam could be held only if the previous year was fruitful, i.e. bumper harvests, there were usually long years of gaps between successive stages, as such Madeen was usually the last Ikam performed by most individuals and was usually regarded as the grandest.

If a man hostsIkam for the sixth time, he is entitled to own a pham. A pham is a long wooden plank of about 25 feet long and it was used for sitting. (Chinir, 2021) The ceremony to acquire such pham is known as Pham Ituk, which means a feast of seat of honour. The pham symbolised the generosity and hospitality of the Ikampa to receive any guest at any time of the day, month or year. Traditionally, such pham is non-hereditary; but the sons could keep it during their lifetime under special circumstances. (Shangkham, 1995) The wooden pham was often destroyed with the demise of the Ikampa because the custom prohibits individuals from relying on the achievements/status/position of their parents/ancestors; every individual is expected to earn his/her position.

Rushong Shangka Iten

The seventh Ikam consists of three events- three days and nights of merry-making, seven days of Fuwraangkuw Yngkhum ritual and another three days and nights of merry making depending on the outcome of the ritual. It is also known as Aanshong Shangka Rii Iten.

Fuwraangkuw Yngkhumis a symbolic imitation of the breeding habits of the hornbill bird (Fuwraang) and hence the name.‘The purpose of Fuwraangkuw Yngkhum ritual was to cleanse the Ikampa and Ikamnuw of their past sins, any wrongdoings and the bloodshed (from the animals slaughtered from the previous Ikam events). It was a form of atonement and purification ritual and the outcome of the ritual would be used to interpret the morals and values of the family. As such, a successful Rushong Shangka outcome would mean that the Ikam couple were sinless and they acquired wealth through honest means.’(Nguruw, 2013) Uneventful outcomes were interpreted in the past as the dishonesty of the Ikam couple and fate and nature punishing them. This Ikam was not taken lightly in the past. There were folk tales of the event going wrong including the death of the husband-wife during the Fuwraangkuw Yngkhum which was considered a bad omen. (Moshing, 2012) In another tale, one Ikampa’sRushong Shangka ritual went wrong and the outcome was him inflicted with lunacy and thereby becoming a ghost (known as BujuurfhuwLae) after his death.(Nguruw, 2013) Only a few individuals were said to reach this stage of Ikam.

Aesii-iteen

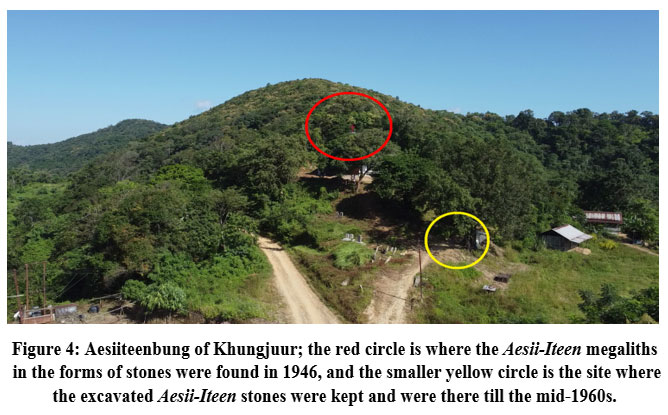

Aesii-teenmeans ‘Counting the stars’. As per the oral tradition, the event was said to symbolise phaethah (bravery). For the Aesii-teen ceremony and to honour the Ikampa, the guests bring stones and pebbles to a site identified by the Ikampa. The stones represent the stars in the sky to symbolise the extraordinary achievements of the Ikampa.

As per the oral accounts, some of the few individuals said to have hosted Aesii-teen were Thompuung, Kuurkam, Vangting and Nijae Ithiim. As per the oral history, Vangting hosted Aesii-Iteen ikam at a hill and the place was named Aesiiteenbung (see Figure 4). (Ringhow, 1998). In the year 1946, rows of megaliths attributed to Vangting’s Aesii-Iteen Ikam were found while excavating the earth; however, those monuments had been lost due to the negligence of the people.(Thomen, 2022)

|

Figure 4: Aesiiteenbung of Khungjuur; the red circle is where the Aesii-Iteen megaliths in the forms of stones were found in 1946, and the smaller yellow circle is the site where the excavated Aesii-Iteen stones were kept and were there till the mid-1960s. Cllick here to view Figure |

Traditionally, only men were allowed to host Ikam, while women and unmarried men were prohibited. Only one woman by the name of Tunuh was brave enough to host Ikam; her extraordinary Ikam continues to be sung till today. The extract of the song goes,

‘Ja..e Daana rumchii o paangna Tunuh burom ateen e.

Ja..e Karu o Zuwrnongpa Siimchim maensha o pih ro…’(Kosha et al., 2010)

[Ja..e By the waterhole of Daana Tunuh is hosting Ikam

Ja..e My bosom, O my honoured clansman May you please lead the dance…]

Ikam is the soul of Bujuur's cultural heritage like folk songs, dance, tales and costumes. It was considered the most important event in the past that it was deemed a bad luck to not attend Ikam held in the village. It was also the only space where young men and women could mingle together, sing and dance, otherwise most would be busy with household or agricultural work with no time for social-merry makings. The songs sung at Ikam also tell the story of the village, about their good and bad times, sufferings and social caricatures. It was such an interesting social event that young men and women would protest if they did not get the opportunity to attend Ikam. (Mosing, 2013) Some of the folk tales related to such dejections regarding Ikam are, Pikhuwn and Shangjeer andTudeen. Pikhuwm and Shangjeer were two beautiful sisters who were prohibited from joining the Ikam event by their parents and were sent to work in the fields; on the way, they were waylaid by enemy armies. One of the sisters committed suicide by jumping into the river while the other sister was killed. (Ringhow, 1998) The song sung by the sisters on their way to the river goes,

‘Khungfhuw durdur o achii raen a

Junuw aeno shee ro sheer o enchii e.

Laarchang aeno karuwsiip o ree kangre

Junuw aeno karuw jong mah rasho e’(Kosha, et al., 2010) (Ledeen, 2013)

[The sounds of drums echo the hills,

But mother forced me to go (fishing)

If the enemies took my head,

Mother, please do not come searching for my bones]

The above song indicated the strength of dejection over not being allowed to join the merry-making, singing and dancing. As such, Ikam being the most important event of the village, young men and women vied to be part of the celebration. They would prepare for months perfecting their dance skills as well as weave the best peen and inih to wear during the event. It was considered a shame to not be part of the Ikam event. In the past, groups of young men and women would often go to neighbouring villages just to participate in the Ikam celebration. (Ledeen, 2013)

Unfortunately, with the tide of time, Ikam started to fade in the 1940s. The last Ikam were held in the year 1943 and 1946. They are remembered to this day, especially by those who participated for good and bad reasons. The 1943 Ikam at Khungjuur abruptly ended in chaos; as the elders narrated, ‘...Ikam dance was going on...then the Japanese Forces showed up...the celebration turned to chaos, everyone ran for shelter...’(Ningkhuwm, 2022) The village was occupied for two years till August 1945. In 1946, a MarzuwIkam was held at Khungjuur which many old folks remember to this day as the last Ikam held in the traditional way.(Ledeen, 2017) (Danichung, 2023) (Danichung’s father was the last person to host Ikam in the year 1946, the following year after the end of WW2.) Prior to 1946, and beginning from the year 1928, there was social chaos within the Bujuur community following the introduction of Christianity among the tribe. For a few years, the Bujuur tradition managed to hold power but as the younger people embraced Christianity en mass, the tradition also began to be discarded. After 1946, Christianity dominated the very lives of the Bujuur. Ikam and other traditional festivals were condemned as unchristian and uncivilised events. With a harsh negative attitude against any pre-Christian traditions and values by the Christianised Bujuur, Ikam faded into history henceforth and survived only in the memories of the older generation. As the memory of Ikam faded, the Bujuur forgot many cultural heritages including folk songs, dances, knowledge, rituals and practices, tales and historical artefacts.

Ikam and Bujuur's socio-economic heritage

The Bujuur people celebrated Ikam for hundreds if not thousands of years. Even though Ikam was celebrated as an important marker of the Bujuur identity, it was never given proper attention after 1946. The abrupt rejection of Ikam or any traditional practices is the result of conversion to Christianity and adopting Western cultures, post-war migrations and a paradigm shift in the socio-economic activities from traditionally agrarian society to a society envisioning services and cash as the measure of economic development. As Ikam was not celebrated, the Bujuur also lost a number of social heritages and the society is presently on the verge of forgetting its socio-economic history. It should be noted that Ikam was not only a symbol of wealth and generosity, but the act of celebrating Ikam also centred around agrarian social capital wherein members of the society participated in the making of the wealth through labour contributions. Accordingly, even not only bestowed honour upon the person (Ikampa) hosting the feast, but it was also an honour for the village to have had such wealthy and generous individuals. A village’s wealth and strength were also measured through the lens of Ikam. As such, many folk songs were composed on the theme of Ikam. In fact, Ikam is the window for society, the present generation and researchers to understand the social geography of the Bujuur people in the past on one hand, and also to understand the historical discourses of identity making of the Bujuur.

The history of Ikam can be said to be as old as the origin of the tribe. According to oral narrations, the first Ikam was said to be held at a place known as Tungphaejuur. (Ringhow, 1998) ‘Tungphaejuur was a historical place not located within the present territory inhabited by the Bujuur. Many believed it to be located far in the east and some speculated it to be the Yellow Valley of modern-day China. The ancestors of Bujuur had earlier migrated from a place known as Kuurdong to settle at Siijuur, from which the nomenclature ‘Bujuur’ was derived. Both these places were believed to be located in ancient Mongolian highlands. From thence, the Bujuur people migrated to Tungphuwjuur and then to Tungphaejuur.’(Chara, 2022) When the Bujuur people settled at Tungphaejuur, agriculture was the main occupation with rice and jobs tears as the main food crops. The fertile land blessed the people with bountiful harvests and thus originated the culture of Ikam. The fertility and life at Tungphaejuur are found in one of the folk songs. The song goes,

‘Kapaam a…Tungphaejuur a

Itae vorning ve muwng isha e.

Itae vorning ve muwng isha e

Buwshae vorning ve muwng ishae e’(Ringhow, 1998) (Moshing, 2012)

[My land…O Tungphaejuur,

I soweditaeh, I harvested grains.

I sowed itaeh, I harvested grains

I sowed buwshae, I harvested grains.]

The above song indicated that the legendary place known as Tungphaejuur was fertile and rightly the place where the ancestors of Bujuur could celebrate Ikam. The land’s fertility was celebrated so much that people sang even if they sowed itaeh (leftover residue found at the bottom of the pitcher after the beer was consumed) and buwshae (pounded and polished rice), the fields would still produce grains.

Another significant historical place renowned for Ikam is the name ‘Ikamphae’. Ikamphae, which means ‘valley of Ikam’ was named so because the Bujuur celebrated Ikam regularly when they settled there. (Korakun, 2012) The Bujuur people at Ikamphae’s indulgence in Ikam, which included competitive drinking of alcohol and merry-making, earned the village a name from the Meiteis as ‘Age khun’.(Angnong, 2012) The reason why the Bujuur people at Ikamphae celebrated numbers of Ikamcould be attributed to the special entitlements for individuals hosting Ikam. As per the custom, anybody who hosted Ikam for at least till the fourth stage was regarded as phaetha (warriors). Accordingly, they would be honoured with a flag-bearing grand funeral procession accompanied by singing and Ikam dance. (Ringhow, 1998) A year after the burial, on the event of Baar Ynthi, Rutha stones would also be erected for the person at a designated place known as Ruthakung. Such social honours were not accorded to regular people who had never hosted Ikam; thus, it was the wish of everybody to get social recognition and be honoured. At the same time, the region around Ikamphae was fertile, thus it allowed the people to pursue their cultural indulgence.

Thus, wherever the ancestors of the Bujuur settled, they held Ikam to celebrate their wealth and the testimonies of these Ikam were left behind in the form of Rutha stones (memorial stones/megaliths). Perhaps, no tribes of the region (Chandel Hills of Manipur) gave as much importance to feast of merit as the ancestors of the Bujuur, for they even divided the feasts into hierarchical stages; thus, merely celebrating Ikam once or twice was not enough for the Bujuur. Instead, an individual needed to host at least four times to get due social recognition and honour. Even though the present Bujuur no longer celebrates Ikam, the once glorious past can be noticed from the megaliths at Khungjuur, Matung and Bujuur Khuwfhuw which are preserved to date. Unfortunately, some of these megaliths have fallen victim to development like the Ruthakung of Khungjuur village as whichwas almost completely destroyed in the early 2000s.

Another feature of Ikam was the erection of Y-shaped totem poles known as ‘sharing’ carved from a special tree known as Iraang-thing. Sharing represented the number of livestock (especially shabaken) slaughtered in the previous Ikam. The most noticeable Sharing would be three sharing, as such, the erection of three sharing became the symbol of Ikam. Sharing is erected in the courtyard of the Ikampa as a symbolic display of his wealth.

Ikam was also an event whereby young men and women showcased their skills and beauty. Men and women dressed in their best attires to partake in the merry-making. One of the most symbolic people during the Ikam event was the lead dancer dressed in Khungiirnuw Inih. Khungiirnuw Inih was traditionally meant for unmarried damsels from a selected rich family. The Inih was said to be a symbolic representation of the wealth and strength of the village and hence named ‘Khungiirnuw Inih’. It has two symbolic meanings, i) khuw means village and ngiirnuw are derived from Ngiirnii which means ‘to stand’, because Khungiirnuw Inihstands out as the most beautiful inih worn by a selected person while performing the Ikam dance, and ii) Khuwng means drum and ngiirnii means to stand, as such Khungniirnii means ‘where the drum stands’ because the inih has a drum pattern on the surface and it was worn during the inauguration of a newly made drum. Either of the meanings, they symbolised that by celebrating Ikam, their village stands out tall and proud among other villages. In connection to that, the erection of Rutha at Ruthakung (usually near the village gate) was also a symbolic display of the village’s strength and wealth and as such, any visitor (outsiders/guests) would respect the village. Unfortunately, the art of Khungiirnuw Inih got lost after the Bujuur stopped celebrating Ikam; and at the same time, since the inih was a ritual dress, it was taboo to wear it on occasions other than the Ikam, so people felt it was unnecessary to preserve the art or the inih.

Another aspect of Ikam was the culture of generosity and sharing of wealth among the Bujuur. The Bujuur society is traditionally renowned for their hospitality and entertainment. The hospitality is made famous in the folk idioms like “Juurku na juurku itung” [a pointed buttock arrives at the house of another pointed buttock]and “Kaven bavasha, kuru ven bavasha[My stomach is filled, my best friend’s stomach is filled]” where the word meanings signify the importance of hospitality, selflessness and generosity. (Kosha, 2009) The Bujuur society of the past believed in hard work and accumulation of wealth; however, they were not into excessive accumulation of wealth while the others lived in poverty. They were encouraged to share their wealth and happiness with their villagers and Ikam was a space for such purpose. By hosting Ikam, individuals displayed their generosity which earned respect from the people. Perhaps, it was such acts of generosity that accorded them with special entitlements and were remembered by the people even long after their death. Also, as a close-knit community with agriculture as the main source of livelihood, people exchanged labour during the process of growing crops. An individual managed to get bountiful harvests was also the result of group work and community participation, as such it was considered rightful for wealthy individuals to share their happiness with their fellow villagers as well as earn trust and respect. Thus, Ikam was also a space to enhance social capital.

Concluding Discussion

Despite the waning of cultural heritage, memory and practices, there were also several attempts by the community leaders to preserve cultural knowledge and bring about cultural awareness amongst the younger generations. Even though Ikam could not be celebrated in its traditional form, adaptations of Ikam found a new interest amongst those who are cultural enthusiasts. For instance, the Moyon Naga Baptist Church initiated an adapted Ikam event by the name “Moyon Christian Ikam” where several Ikam components were presented including Ikam dance, songs, Buwtaang ynjeh and folklores. (The Christian Ikam. Penaching, 2000) Kapaam village also emulated the Ikam tradition by planting three Sharing on the occasion of the village’s Golden Jubilee in the year 1998; however, due to lack of cultural awareness, local superstition and overzealous faith in Christianity compelled the village to remove the Sharing a few years later. (Chara, 2021). Individual awareness of the importance of cultural items, especially of Ikam, has become a new trend among the women folks who are now investing in acquiring dresses and jewelleries associated with Ikam. In recognition of the significance of Ikam and to preserve the heritage, an Ikam was also hosted by the Iruwng (Chief) of Khungjuur in the year 2018. The Bujuur Aanchung Puh, as the cultural body of the tribe, also recognised Ikam as one of the most important cultural heritage that needs to be revived and has encouraged wealthy individuals to host Ikam. However, despite the support of the society to revive Ikam, it is observed that women continue to be discriminated against when it comes to hosting Ikam as the society still believes that women should not host Ikam even though the present Bujuur society is characterised by women dominating the economic sector.(Serbum, 2018)

Against the backdrop of the discontinuance of traditional Ikam and thus the loss Ikam related heritage, the influence of modernity and social media, cultural exchanges with other communities and the resurging awareness amongst the Bujuur to revive their once discarded traditions and customs, there is also the nuanced challenges on the themes of cultural appropriations, misinterpretation of the past cultural heritage for the leaders’ utilitarian visions and the sustainability of any surviving cultural artefacts. It is observed that the Bujuur society desires to revive their lost customs, but at the same time, they are also wary of the religious (Christianity) implications. There is also the fear of cultural appropriation as cultural items are often misused as entertainment or exotic artefacts for public display. In the backdrop of very few individuals having adequate knowledge and awareness of the Bujuur cultural history, there is also the fear of cultural knowledge being either forgotten or mistranslated, as it had happened with the customs and practices when the Bujuur Aanchung Puh mistranslated customs and traditions as Customary Law.(Bujuur Kastam, 2008)

Ikam, as the most prestigious traditional feast of merit, is a window to understand the historical social-economy of the Bujuur. Having been celebrated since time immemorial, Ikam shaped and reshaped the Bujuur culture and provided a space for the Bujuur community to express their rich cultural heritage through merry-making, songs, dances and even megaliths. However, it is unfortunate that the Bujuur community ignored Ikam as they embraced modernity and Christianity. In the haste to prove themselves as modern people, their rich cultural heritages were neglected in favour of westernised and Christianised lifestyles. Today, Christian festivals have replaced traditional festivals and modern love songs, western music and Christian hymns have replaced folk songs. Even if there were attempts to revive traditional events, their historical significances are lost as revived events cater to the utilitarian outlook of the modern Bujuur considering cultural heritage as decorations and events as annual chores, instead of grounding on the principles of sustaining the symbolisms, significances and importance. The present Bujuur people are not only losing their cultural heritage, memory and history, but they also slowly losing their unique traditions and identifying features that set them apart from other communities; and one of the main routes to counter the loss of cultural heritage is active awareness and participation of the younger people so that they may cultivate interests towards cultural and identity preservation.

Acknowledgement

Words of gratitude to Bujuur elders, especially Beshop Ngoruw, Ng Korakun, Moshing Nungchim, Ledeen Roel, Lekham Roel and Phamnong Chinir for sharing their experiences of Ikam and meanings of folk songs. The authors would like to also acknowledge Thomen Chara and Gina Shangkham for their insights on the megaliths of Khungjuur village.

Funding Sources

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Chara E. Identity in the Oral History of Bujuur Naga. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 1(1). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.1.1.05

CrossRef - Bujuur Aanchung Puh. (2021). “Moyon Census”

- N.A. (2007). Golden Jubilee Souvenir (1951-2007). Tamu, Myanmar: Moyon Naga Baptist Church.

- Shangkham, G. (1995). “A brief accounts of the Moyons”. In N. Sanajaoba (Ed.), Manipur Past and Present Volume 3 (pp.440-456). New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

- Chara, E. (2021). Let me take a photo with the Shabaken: Reflections on Ikam among the Bujuur Naga. Ethnography, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381211039369

CrossRef - Ringhow. N. (1998). Khungjuur. Komlathabi

- Ledeen, R. (2017, February 20). Personal Communication.

- Moshing, N. (2012). Bujuur Lamthing Ikar. Heigrutampak

- Danichung, N. (2023, October 2). Personal Communication.

- Chinir, P.R. (2021). Social change among the Moyon tribe of Manipur. Maram, Manipur: DBC Publications.

- Nguruw, K. (2013, May 15). Personal Communication.

- Thomen, C. (2022, July 20). Personal Communication.

- Kosha, Donald. (2010). Bujuur Kastam La: Moyon Folk Songs. Imphal

- Mosing, N. (2013, May 29). Personal Communication.

- Ledeen, R. (2013, May 10). Personal Communications.

- Ningkhuwm, R. (2022, April 25). Personal Communication.

- Chara, E. (2022). Ethnographic profile of the Bujuur tribe: Notes on history, society and culture. Antrocom Journal of Anthropology, 18:1, 233-258.

- Korakun, N. (2012). “Iruwngpa Kuurkam”. In N.G.S. Moyon (Ed.), Ng Kuurkam Moyon (pp.47-58). Komlathabi: Bujuur Aanchung Puh.

- Angnong, R. (2012) “The origin, migration and settlement of the Moyons (1986)”. In N.G.S. Moyon (Ed.), Ng Kuurkam Moyon (pp.26-41). Komlathabi: Bujuur Aanchung Puh.

- Kosha, D (Comp.). (2009). A collection of Moyon Folk Literature. Author Published.

- N.A. (2000). The Christian Ikam. Penaching: Moyon Naga Baptist Association.

- Chara, E. (2021). Let me take a photo with the shabaken: Reflections on ikam among the Bujuur Naga. Ethnography, Online First Publication, 1-25.Doi: Doi: 10.1177/14661381211039369

CrossRef - Serbum, D. 2018. The Changing Status of Women in Moyon Society”. In Naga Women’s Union (ed.), The Place of Women in Naga Society (pp.73-91). Guwahati: Christian Literature Centre.

- N.A.(2008). Bujuur Kastam (Moyon Customary Law). Kapaam: Bujuur Aanchung Puh.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.