The Influences of Socio-Cultural Characteristics on Public Low-Cost Residents Satisfaction: A Case Study on PPR Seri Aman Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Mazura Mahdzir1  , Tan Xi Yi1 , Nik Fatma Arisya Nik Yahya2 , Sharifah Mazlina Syed Khuzzan3 , Nafisah Ya’cob4

, Tan Xi Yi1 , Nik Fatma Arisya Nik Yahya2 , Sharifah Mazlina Syed Khuzzan3 , Nafisah Ya’cob4  , Noorhidayah Sunarti5 , Zetty Pakir Mastan5

, Noorhidayah Sunarti5 , Zetty Pakir Mastan5  and Nurulhuda Ahamad5

and Nurulhuda Ahamad5

1Department of Quantity Surveying, Faculty of Built Environment, Tunku Abdul Rahman University College, Jalan Genting Kelang, Setapak, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia .

2Department of Quantity Surveying, Faculty of Engineering and Quantity Surveying, Inti International University, Persiaran Perdana BBN Putra Nilai, Negeri , Sembilan Malaysia .

3Department of Quantity Surveying, Kulliyyah of Architecture and Environmental Design, International Islamic University Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia .

4Department of Quantity Surveying, Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Management dan Teknologi Tunku, Abdul Rahman (TARUMT), Malaysia .

5Department of Quantity Surveying, Faculty of Engineering and Quantity Surveying, INTI International University, Nilai, Negeri Sembilan Malaysia .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.5.2.07

Copy the following to cite this article:

Mahdzir M, Yi T. X, Mohamed N. N. A. N, Yahya N. F. A. N, Mastan Z. P, Sunarti N, Ahamad N, Khuzzan S. M. S, Ya’cob N. The Influences of Socio-Cultural Characteristics on Public Low-Cost Residents’ Satisfaction: A Case Study on PPR Seri Aman Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2022 5(2).

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.5.2.07Copy the following to cite this URL:

Mahdzir M, Yi T. X, Mohamed N. N. A. N, Yahya N. F. A. N, Mastan Z. P, Sunarti N, Ahamad N, Khuzzan S. M. S, Ya’cob N. The Influences of Socio-Cultural Characteristics on Public Low-Cost Residents’ Satisfaction: A Case Study on PPR Seri Aman Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2022 5(2).. Available from:https://bit.ly/3X461xj

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 05-09-2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 10-10-2022 | |

| Reviewed by: |

Akinluyi Muyiwa L

Akinluyi Muyiwa L

|

|

| Second Review by: |

Abimbola Olufemi Omolabi

Abimbola Olufemi Omolabi

|

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr Rohaiza Rokis | |

Introduction

Vision 2020 aimed to develop a Malaysian society economically growing fully as well as united and enjoyed a high quality of life. The Malaysian government introduced the National Development Policy (NDP) under the Second Outline Perspective Plan (OPP2) to aim the vision. The housing policy ensures that every Malaysian can own a reasonable and affordable house and utilize related facilities, especially for low-income families (Ministry of Housing and Local Government Malaysia 2011). Through housing programmes, several affordable house schemes were provided to people, such as People's Housing Program (PPR), Rumah Mesra Rakyat (RMR), Perumahan Penjawat Awam Malaysia (PPAM), and 1 Malaysia Housing Project (PR1MA) (The Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit 2021).

The development of housing often needed to be considered both economic and socio- cultural factors. Certain variables, such as residents' experience and socio-cultural backgrounds, have influenced how people evaluate their living environment (Makinde 2015). Hence, the resident's assessment from the different socio-cultural background reflected a different level of satisfaction. The social or cultural components include the residents' ethnic, religious, and household size. Therefore, it is essential to determine the impact of residents' socio-cultural backgrounds on their satisfaction with low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur to identify residents' needs and improve their quality of life.

Problem Statement

Although the current poverty line index in Kuala Lumpur has recorded a small proportion, low-income earners still face problems in purchasing affordable housing. The high land and construction cost increased the housing price and brought challenges to Kuala Lumpur's poorest (Bakhtyar et al. 2013). According to the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2020, several issues associated with low- cost housing have been identified, including low space requirements, a lack of community amenities, a scarcity of car parking spaces, high maintenance costs, and poor construction and material quality in low-cost housing projects (Hashim et al. 2012). Therefore, it shows that Malaysia's housing policies still failed to provide a comfortable living area for the low-cost income group.

According to Ismail et al. (2020), it was discovered that the design evaluation of public facilities in low-cost housing did not wholly satisfy the basic requirements of the residents, especially for the comfort of youths and it could influence the development of youth psychology. They failed to consider residents' cultural backgrounds. Their research was narrowly focused because it only examined public facilities, excluding other variables such as dwelling unit features, neighbourhood facilities, and cultural conditions, all of which are significant to indicate residents' satisfaction. Besides, Mohit, Ibrahim and Rashid (2010) also examined the new design for low-cost public housing on residential satisfaction by analysing the two sheltered components and three non-sheltered components. The result showed that the five housing components also have a possible association with the user's satisfaction. Nevertheless, they did not study the socio-cultural factors that are crucial to determine the proper house design.

Other housing satisfaction studies have focalized on residential and neighbourhood satisfaction, security, and maintenance. These scholars have centred the majority on sustainable housing requirement for the low-cost income group, and housing satisfaction evaluation act as a benchmark of residents' quality of life (Karim, 2012).

However, studies related to the resident’s cultural background in the living environment remains insufficient. In fact, the existing studies mainly focused on the residents' demographic characteristics as the influential factors. Towards creating a more unified community and enhance long-term sustainability in Kuala Lumpur's low-cost housing development, this paper tries to measure the Malaysians' satisfaction in low-cost public housing based on their socio- cultural background. To achieve this aim, two objectives are formulated as follows; (i) To identify the socio-cultural characteristics of residents (ii) To analyse the relationship between residents’ satisfaction and their socio-cultural characteristics.

Literature Review

Overview Low-cost Housing in Malaysia

The Malaysian government always placed providing housing for low-income people as a primary element of the housing policy. Therefore, the related provision has become a priority in the Five Years National Plans since independence, and it was officially introduced in the First Malaysia Plan (1966-1970) for promoting the well-being of the lower-income population (Zaid & Graham 2011). The state government cooperated with the federal government to develop the state's low-cost housing plan. To ease the government's burden, a new policy was implemented in 1981 for private housing developers, requiring them to provide a minimum of 30% of this housing type for every residential development (Shuid 2008). Therefore, it is unique in Malaysia because the state controls the allocation of low-cost housing, and the project is carrying out by either public or private sectors.

In the Fourth Malaysia Plan (1981-1985), the Malaysian government specifically defined low-cost housing as a housing unit that incorporates particular characteristics. The low- cost housing ceiling price was fixed at RM 25,000 based on the place and type of house and household income. It only sold for monthly household incomes less than RM 750 (Agus 1997).

The government later newly classified the selling price to RM 42,000 to improve the quality and meet the private developer's requirement (refer to Table 1) (Ministry of Housing and Local Government 1998). The new design specifications for low-cost housing were also introduced to advance accommodation variety to fit residents’ preferences with the updated selling prices.

Table 1: The difference in the low-cost housing price structure and requirement for monthly household income in 1998 (Ministry of Housing and Local Government 1998)

|

|

Price/ unit |

Household Income/month |

|

Before June 1998 |

Below RM 25,000 |

Below RM 750 |

|

After June 1998 |

Below RM 42,000 (Depend on the position of housing) |

Below RM 1,500 |

Previously, most housing developers only focused on meeting their pre-determined goals and tended to neglect the housing quality. As a result, the low quality of housing has failed to meet the resident's housing needs, comfort, and religious demands (Tan 1980). Fortunately, the government's housing policies kept renewed and shifted from providing better quality, such as the primary objective stated in the Tenth Malaysia Plan (RMK10) is to ensure the way to quality and affordable housing (Economic Planning Unit 2010).

Research Context

Due to the limited land space and its exorbitant prices, normally, the low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur implemented the high-density housing concept (Leong 1979). Therefore, the Peoples' Housing Programme (PPR) is built to replace slum housing and meet low- income people's needs, especially around Kuala Lumpur. PPR housing is focusing more on the family. PPR housing consists of PPR for sale (PPRM) and PPR for rent (PPRS). For example, PPR housing in Kuala Lumpur included PPR Sg. Besi, PPR Kg Batu Muda, and PPR Taman Wahyu II (Construction Industry Development Board Malaysia 2019).

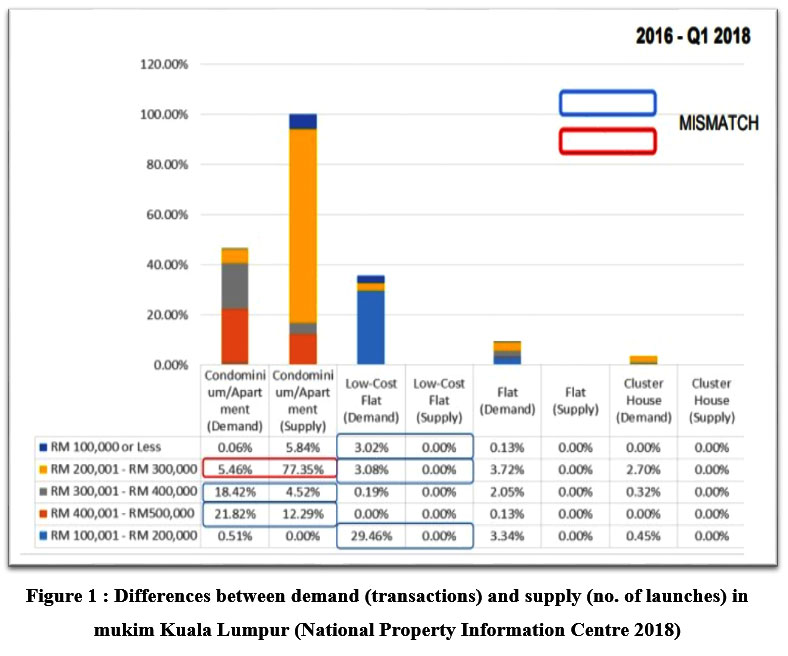

The City Hall Kuala Lumpur (DBKL) used the house price structure set by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government to determine the selling price of low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur, which cannot exceed RM 42,000. In Kuala Lumpur, as shown in Figure 1, the number of low-cost housing launches was zero, while the demand for low-cost housing was 3.02%. Hence, the demand and supply in Kuala Lumpur still have a significant gap in 2018. This was due to the increasing number of citizens from rural to urban areas (Aziz, Ahmad and Nordin, 2012).

|

Figure 1: Differences between demand (transactions) and supply (no. of launches) in mukim Kuala Lumpur (National Property Information Centre 2018) Click here to view Figure |

Identify Dwelling Unit Features

As a special housing category, high rise low-cost housing is regulated by the National Housing Standard for Low-cost Housing Flats (CIS 2), which provides planning and design guidelines. All these projects must comply with the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB)’s guidelines to ensure that all construction is up to the standards. Aside from that, the specification must meet the requirements of the Street, Drainage and Building Act 1976 (SDBA) and the Uniform Building by Laws 1984 (UBBL), which include safety, complete infrastructure, health and physical development, and community development (Sulaiman, Ruddock & Baldry 2005; Sufian & Rahman 2008). All of these standards have tended to result in a better lifestyle for the lower- income group.

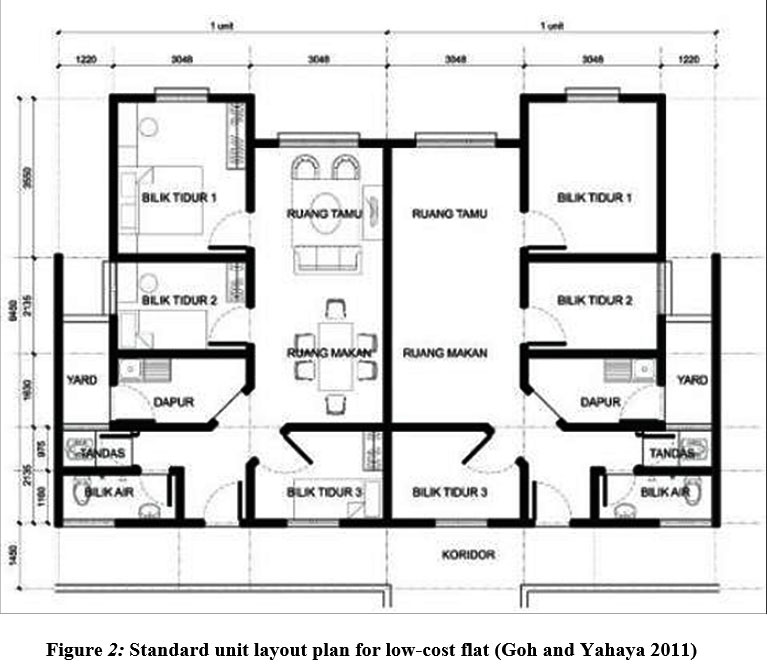

The government have been issued strict guidelines for each unit of low-cost high-rise housing in 1998 and 2002. There was an amendment in the minimum floor space requirements and also the number of rooms and toilets (refer to Table 2). The size of the room was accorded to the CIDB defined (refer to Figure 2) (Ministry of Housing and Local Government of Malaysia 2002; Shuid 2008). However, there was a difference in the size of room function between CIS 2 and the existing design of PPR (refer to Table 3) (CIS 1998; Goh & Yahaya 2011).

Table 2: Comparison of the design specification of low-cost housing in 1998 and in 2002 (Shuid 2008; Ministry of Housing and Local Government of Malaysia 2002)

|

Description |

In 1998 |

In 2002 |

|

Elements |

Minimum requirement (area or number of room) |

Minimum requirement (area or number of room) |

|

Floor space |

550 sq. ft. |

63m2 |

|

Bedroom |

2 |

3 |

|

Kitchen |

1 |

1 |

|

Toilet |

1 |

2 |

|

Living room |

1 |

1 |

|

Yard |

- |

1 |

Table 3: Comparison of room area between CIS 2 and PPR (CIS 1998; Goh & Yahaya 2011)

|

|

CIS 2, 1998 |

PPR, 2000 |

|

Room Function |

Area (m2) |

|

|

Living + Dining |

25.20 |

24.19 |

|

Yard |

- |

2.90 |

|

Master Bedroom |

11.70 |

10.82 |

|

Bedroom 1 |

9.90 |

6.67 |

|

Bedroom 2 |

7.20 |

6.51 |

|

Kitchen |

5.40 |

4.52 |

|

Bathroom 1 |

1.80 |

3.07 |

|

Bathroom 2 |

1.80 |

1.71 |

|

Total Area |

63.00 |

60.38 |

|

Figure 2: Standard unit layout plan for low-cost flat (Goh & Yahaya 2011) Click here to view figure |

Housing design and quality affected both the user and the community. Developers and designers should be mindful of their responsibilities and adopt high design quality in housing projects (Chohan et al. 2015). Although CIS 2 has enhanced the standard of living for low-income households, the design quality has not met residents’ expectations. (Sufian & Rahman 2008). Hence, to improve the design criteria for low-cost housing, it is important to obtain information from residents about their requirements or preferences.

Neighbourhood Facilities

Neighbourhood characteristics are divided into four elements by Andersen (2011) to ensure that the housing area is suitable to be occupied. Besides that, Azmi and Karim (2012) identified that neighbourhood facilities are based on the people usually reach by walking. The explanation of the characteristics is tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4: Characteristics of suitable building’s surrounding and neighbourhood (Andersen 2011; Azmi & Karim 2012)Types of characteristics.

|

Types of characteristics |

Explanation |

|

Physical Environment |

|

|

Social Environment |

- the area’s status, safety, social network and lifestyle |

|

Location and Public Facilities |

|

|

Location and Transportation |

|

Few authors defined neighbourhood facilities that should be provided in a residential environment. It can conclude that the type of neighbourhood services and facilities can be grouped as commercial facilities, recreational facilities, health facilities, religious facilities, institution facilities, support services and others (refer to Table 5). The suitable distance and location for the neighbourhood facilities also are summarized in Table 6.

Table 5: Types of neighbourhood facilities (Ross 2000; Asiyanbola, Raji & Shaibu 2012)

|

Types |

Example |

|

Commercial facilities |

Local shops, events centres, shopping centres |

|

Recreational facilities |

Parks, leisure centres |

|

Health facilities |

Clinic, hospital, health-care centres |

|

Religious facilities |

Temples, churches, shrine, mosques |

|

Institution facilities |

Schools |

|

Support services |

Bank, post office. police stations, fire service stations |

|

Others |

Traffic, sidewalks, connectivity of paths safety, aesthetic pleasure |

Table 6: Suitable distance and location for neighbourhood facilities.

|

Neighbourhood Facilities |

Suitable Distance and Location |

Author (s) |

|

Institution facilities (Elementary school) |

|

De Chiara & Koppleman (1925), Perry (1939) |

|

Commercial facilities |

|

De Chiara & Koppleman (1925), Rani (2013) |

|

Health facilities |

|

Rani (2013) |

|

Recreational facilities |

|

De Chiara & Koppleman (1925) |

|

Support services (bank, post office) |

|

Rani (2013) |

Despite government clinics in all areas of Kuala Lumpur, these services are not uniformly dispersed according to population distribution (Kuala Lumpur City Hall 2008). This problem mainly affects low-income individuals who cannot afford care at private clinics and live long distances from public facilities. Furthermore, according to the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan, although there are neighborhood and local parks in all strategic areas, these facilities are not spread equally, eased on population distribution (Kuala Lumpur City Hall 2008). The lack of leisure facilities was identified due to the city's limited space and high land value. As can be seen, the neighborhood facilities were essential for residents to utilize in their daily routine. While developing low-cost housing, these facilities' location and design should also be considered in development planning.

Concept of Residential Satisfaction

According to Mohit and Raja (2014), before defining the concept of resident’s satisfaction, the terms housing and satisfaction should be defined separately. They concluded that housing is not only an individual’s housing structure. It also consists of the entire physical and social elements that formed the housing project. The various definition of residential satisfaction is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7: Summary of definition of residential satisfaction.

|

Author (s) |

Definition |

|

Parker & Mathews (2001) |

Satisfaction is a continuum of comparison of what has been received and what has been expected. |

|

Campbell, Converse & Rodgers (1976) |

The perception of the difference between residents' reality and expectations is how much one acquires to one's level of aspiration. |

|

McCray & Day (1977); Djebuarni & Al-Abed (2000); Ogu (2002) |

The level of comfort expressed by a person or a household member evaluates their expectations and feelings about the current housing situation and environment. It determines residents’ observations of drawbacks in their current housing conditions to improve the current situation. |

According to Ogu (2002), if the resident's housing condition meets the requirements, they were expected to show a high housing satisfaction level. The criteria such as housing unit condition, privacy in the house, and maintenance of environmental facilities. In summary, residential satisfaction means that residents judge their satisfaction based on comparing real needs and expectations. It is also a way to express individual or family members’ desires and feelings about their houses that are close to their favourite preference.

Factors related to Socio-cultural characteristics

Many factors related to socio-cultural characteristics affected the level of residential satisfaction. The factors are discussed and further detailed in the following sub-section.

Housing Characteristic

According to Huang and Du (2015), the fundamental measure of an objective residential setting is housing characteristics. Housing characteristics presented a more significant part in determining housing residents' satisfaction. Thus, residential satisfaction is closely associated with the housing's structural attributes such as size, number, location, and quality of building features. These features referred to the bedroom, kitchen, yard, residence hall, bathroom, and dining space (Salleh 2008; Mohit & Raja 2014).

Besides that, studies conducted by Mohit, Ibrahim and Rashid (2010) on the residents of newly designed Sungai Bonus discovered that housing features, particularly housing unit size, showed a positive relationship with residential satisfaction. In PPR Kuala Lumpur, the residents were satisfied with the current unit features (Goh & Yahaya 2011). However, Mohd-Rahim et al. (2019) found that most PPR occupants felt dissatisfied with the size of the unit but happy with the housing’s layout space. Chen, Zhang and Yang (2013) gathered data from a Chinese residential survey in Dalian and discovered that they prefer larger housing.

Based on the previous studies, the PPR residents were quite satisfied with the bedrooms and bathrooms. Only bedroom 3 and bathroom 2 received a lower level of satisfaction than the other bedrooms and bathroom (Salleh 2008; Goh & Yahaya 2011; Anuar & Ramele 2017). Additional features such as kitchen, yard, dining room, and cloth line facilities were the dissatisfied unit design in affordable housing (Salleh 2008; Anuar & Ramele 2017; Ishak, Mohamad Thani & Low 2018; Dzulkalnine et al. 2020). Moreover, Goh and Yahaya (2011) pointed out that the position of the kitchen and yard were unsuitable because the cooking smoke from the kitchen would escape through the yard and the yard difficult to get the sunlight unless it faced north-south. In short, residents’ dissatisfaction was mostly concerned on the common area of PPR housing.

In addition, in public housing in Nigeria, Ibem and Amole (2013) discovered that occupants showed extremely satisfied with their residences' privacy. Furthermore, Morris, Crull and Winter (1976) found that the increased number of rooms increased housing satisfaction. They concluded that the higher the density in the living area, the lower the housing satisfaction level. Hence, it can determine that residents were more satisfied with the larger housing spacing in their living area.

Neighbourhood Facilities

Satisfaction with the neighbourhood was one of the primary determinants in housing satisfaction (Ibem & Amole 2013). Huang and Du (2015) also stated that neighbourhood facilities could define the level of life convenience and influence residential satisfaction. The ways for a family to evaluate a neighbourhood is based on the four main criteria. The first criteria are that the neighbourhood facilities should be predominately residential. Second, it should be able for the residents to access quality institutions. The condition of the paths and roads is the third criteria for them to consider. Lastly, they also put homogeneity into the assessment regarding social class, culture, and ethnic group (Morris, Crull & Winter 1976). Many neighbourhood facilities are provided in the community, such as transportation, academic institutions, medical centres, retail shops, financial institutions, clinics and community halls.

Ha (2008) concluded that both parking and landscaping facilities were dissatisfied by the resident who stayed in Korean' public housing, whereas they were mostly satisfied with the availability in the other three facilities, particularly healthcare, shopping and banking facilities. In Kuala Lumpur, residents of public low-income housing commented that it was near to city centre, also easy for them to reach the playground and public facilities such as hospitals, police stations, and fire stations, but also dissatisfied with the parking facilities (Sulaiman, Hasan & Jamaluddin 2016; Dzulkalnine et al. 2020). Besides that, Salleh (2008) and Mohd-Rahim et al. (2019) also discovered that the parking lots were unsatisfactory in low-cost housing. In addition, Lu (1999) discovered that residents of Hong Kong's public housing were dissatisfied with public transportation. In low-cost housing in Malaysia, Salleh (2008) also stated that residents who stay in Terengganu were dissatisfied with the public transport provided within the neighbourhood, but Mohd. Rahim et al. (2019) found that residents who stayed in Kuala Lumpur were most satisfied with the distance to public facilities. Besides that, Mohd-Rahim et al. (2019) also discovered that the location of PPR was strategic and near to the residents’ workplace.

Awotona (1991) investigated that neighbourhood dissatisfaction happened because of the residents' housing estates' geographical location and travelling distances. The travelling distances included children travel to school, residents travel to working place, and medical centres. For instance, respondents in Nigerian public housing felt the most unsatisfied with the proximity to shopping amenities because of the distance (Ibem & Amole 2013). Moreover, Ozo (1990) also noted that residents' convenience to take public transportation and reach the shopping mall was also part of the assessment factors. Thus, when assessing residential satisfaction among public housing residents, location factors were fundamental (Baker 2002). Therefore, besides considering residential satisfaction based on housing conditions, the neighbourhood facilities are also important in residential satisfaction. Most residents were concerned about neighbourhood facilities is the travel distance and convenience.

Household’s Socio-cultural Characteristic

Housing and socio-cultural factors are inextricably linked. It is an intangible factor that can influence one's behaviour, relationships, perceptions, and way of life. As a result of the development of cultural, religious, educational, and social conditions, some socio- cultural factors such as beliefs, attitudes, habits, and lifestyle behaviours have emerged (Bennett & Kassarjian 1972; Adeleke, Oyenuga & Ogundele 2003). Malaysians come from various cultures, including Malay, Indian, and Chinese, all of which have long- standing and powerful cultural traditions that influence their daily lives. As a result, the cultural aspect of housing must be considered (Mohamad 1992).

Not only are housing structures ignorant of individual needs, but the units, with their Western layouts and cultural influences, are completely ignorant of the practices and lifestyles of all three cultures (Mohamad 1992). One of the factors is compartmentalizing different activities into the designated room is completely unfamiliar to Malay culture. Furthermore, these rooms' spatial relationships directly contrast the three cultures' living patterns, such as having the kitchen next to the living room. Hence, the housing units are unsuitable for anyone.

According to a study by Yap and Lum (2020), the results of Feng Shui considerations by ethnic groups in terms of frequency are Chinese and Indian in terms of numbers, while Malay in terms of interior arrangement. Differentiated from the Chinese and Indians, the Malays place a greater emphasis on the "living room". Surprisingly, the Malays placed a greater emphasis on "room shape" than on "street location." Besides that, the Malays were more concerned with the house's internal arrangement than with the environment. It is worth noting that both the Chinese and the Indians frequently related numbers with Feng Shui considerations.

"Orientation" topped the list for the Chinese in Yap and Lum's (2020) results. Furthermore, Mohamad (1992) stated that these three ethnic groups have different orientation preferences. Malay people prefer the west, while Chinese people prefer the east due to Feng Shui; Indians prefer the east or west over the south.

In Islam, visual privacy is important. In Muslim homes, visual privacy has always been a crucial component and consideration. It also impacted the main entrance's location and design, the division of areas into public and private areas, and separate places for different gender parents and kids (Rahim 2015).

Besides that, Abdu et al. (2014) concluded that household size and age had a relationship with residential satisfaction, but educational level and length of residence were irrelevant to the assessment. Prior research has suggested that socio-cultural factors play a fundamental role in determining residential satisfaction. The decision to standardise is heavily influenced by culture. These aids in determining the housing value for various individuals, such as different cultures or sociology-demographic profiles. In Malaysia, other ethnic groups from diverse backgrounds live in low-cost public housing. This factor must take into account to live harmoniously and peacefully in the same residential area.

Materials and Method

The method used for this paper is quantitative data collection. The primary data was acquired through a questionnaire survey with closed-ended questions and a Likert scale to measure respondents' housing satisfaction levels. It consists of two extremes (strongly dissatisfied and satisfied) and a neutral preference associated with the middle response to satisfaction level (dissatisfied and satisfied). An ordinal scale is used to measure the rating. The targeted group are the residents who were staying in PPR Seri Aman. Based on the Yamane formula, a sample of 95 residents (n = 95) was chosen from a sum of 1600 house units (N = 1600). The sample size means 5.94% of the total housing population, with a 90% confidence level, and the results will not vary more than ±10%. A purposive sampling design has been chosen for this research. The selection is based on several reasons: (i) the accessibility (location factor and time constraints) and (ii) confidentiality basis (openness to shares their points of view) (iii) they are the (v) they are the permanent residents that can be rely on and learned most as stressed by Meriam (2001). This is consistent with Kumar (2018) who added that this form of sampling remains suitable for small population (ie case study research of PPR Sri Aman)

Meanwhile, Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) Version 26 is used to analyse the collected data for results discussion. Factor analysis is used to identify the socio-cultural factors. This data further uses Pearson's correlation analysis to measure the degree of the linear relationship between two variables (socio-cultural factors and residential satisfaction).

Sample Composition

The questionnaires were created in Google Form, and the target is the residents who stay in PPR Seri Aman. The link to the survey form was posted on the PPR Seri Aman’s social media page, and the total 93 responses were received after the deadline of three weeks. The frequency statistics of the 93 respondents in PPR Seri Aman are categorized into gender, age range, ethnicity, religious, length of residency, household size, and education level (refer Table 8).

Table 8: Profile of the respondents.

|

Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

42 |

45.2 |

|

Female |

51 |

54.8 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

18-30 |

44 |

47.3 |

|

31-40 |

20 |

21.5 |

|

41-50 |

25 |

26.9 |

|

>50 |

4 |

4.3 |

|

Ethnic |

|

|

|

Malay |

27 |

29 |

|

Chinese |

37 |

39.8 |

|

Indian |

28 |

30.1 |

|

Others |

1 |

1.1 |

|

Religious |

|

|

|

Muslim |

29 |

31.2 |

|

Buddhist |

35 |

37.6 |

|

Hindu |

23 |

24.7 |

|

Others |

6 |

6.5 |

|

Length of Residency |

|

|

|

1 |

12 |

12.9 |

|

2 |

20 |

21.5 |

|

3 |

22 |

23.7 |

|

>3 |

39 |

41.9 |

|

Household size |

|

|

|

1-3 |

23 |

24.7 |

|

4-6 |

54 |

58.1 |

|

7-9 |

11 |

11.8 |

|

>9 |

5 |

5.4 |

|

Education level |

|

|

|

Primary |

1 |

1.1 |

|

Secondary |

45 |

48.4 |

|

Tertiary |

42 |

45.2 |

|

Others |

5 |

5.4 |

Table 8 shows the gender frequency among respondents in PPR Seri Aman. Among the 93 respondents, the major gender group of respondents is female, with 51 responses received (54.8%). While for male respondents, there are 42 responses received (45.2%). As for the age range of the respondents, it can categorized into young adults (ages 18-30 years), middle-aged adults (ages 31-40 years), older adults (ages 41-50 years), and senior adults (aged older than 51 years). The majority age range of respondents in PPR Seri Aman is between 18 and 30, with 47.3%. The second highest age range of 93 respondents received is between 41 to 50 years old, with 25 responses received (26.9%), followed by 20 respondents (21.5%) who are between 31 to 40 years old. Lastly, only 4 replies (4.3%) were from the respondents who are above 50 years old.

Meanwhile, most of the respondents in PPR Seri Aman are Chinese, with 37 responses received (39.8%) among the total number of 93 respondents. Indian respondents and Malay respondents are received similarly, with 28 replies (30.1%) and 27 responses (29.0%). There is only 1 response (1.1%) received from the other ethnic. Within religious context, majority of the respondents are Buddhist which received 35 responses (37.6%). 29 respondents (31.2%) are Muslim, which is the second-highest proportion of religious respondents in PPR Seri Aman. It was followed by 23 respondents (24.7%) who are Hindu and received 6 responses (6.5%) under other religions.

Whereas for length of residency, most of the respondents (39 responses, 41.9%) have stayed over three years. There are 22 respondents (23.7%) who already stayed three years, and there are 20 responses (21.5%) received from the respondents with two years of residential experience. Lastly, 12 responses (12.9%) were obtained from the respondents with only one year of residential experience in PPR Seri Aman.

For household size, most respondents (54 responses, 58.1%) stay together with 4 to 6 people in a house. Then, following by 23 respondents (24.7%) stayed together with 1 to 3 people. Also, 11 responses (11.8%) were received from the respondents staying with 7 to 9 people. The household size for 9 people is only 5 responses (5.4%) received.

As for educational level, the number of respondents who graduated from secondary education and tertiary education is likewise, which recorded 45 responses (48.4%) and 42 responses (45.2%) correspondingly. 5 respondents (5.4%) finished their study at other education levels. At the same time, only 1 respondent (1.1%) completed till primary education level.

Results and Discussion

Factors related to Socio-Cultural Characteristics

This study examined how the residents of the PPR Seri Aman responded to the different aspects of housing necessity. The analysis method is factor analysis to determine the main factors affecting residential satisfaction from these 26 questions. The interpreted data results extract 6 factors, show Eigenvalues exceeding 1, and these factors are deemed for 71.68% of the total variance across 26 variables (refer to Table 10).

According to IBM (2014), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy measure is statistical data that determines the proportion of variance in these study variables that underlying factors may cause. In this research, the value is 0.859, higher than 0.5, a high value (close to 1.0). It means that the responses given with the sample are adequate. Besides that, Table 9 shows the value of Bartlett’s test of sphericity is 0, not more than 0.05 of the significance level. It also implies that this analysis is valuable with the data.

Table 9 : KMO and Bartlett's Test.

|

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. |

.859 |

|

|

|

Approx. Chi-Square |

1576.977 |

|

Bartlett's Test of Sphericity |

Df |

325 |

|

|

Sig. |

.000 |

The factor analysis identified the six main factors: the distance to neighborhood facilities, common housing area and privacy, sleeping area, management of housing area, overall housing design and size, and yard.

The first factor was labelled distance to neighbourhood facilities due to the high loadings by a set of related variables, including distance to clinic/hospital, shopping, market, support services, nearest town centre, workplace, school, and religious locations. This first factor explained 18.395% of the variance in all 26 components.

Next, Factor 2 derived was labelled common housing area and privacy. The important variables of this factor are the size and layout of bathroom 2, kitchen, bathroom 1, living area, dining space, and level of privacy. The variance explained by this factor was 13.790%.

The third factor relates to a set of variables of sleeping area in dwelling unit features. The size and layout of bedroom 2, bedroom 3, and master bedrooms are this factor's main components, which explained 12.297% of the variance.

Another dimension was Factor 4, labelled as management of housing area, related to the availability of parking, distance to take public transport, playground, traffic nearby, and sidewalks and connectivity of paths safety. This component accounted for 11.277% of the variance.

The fifth dimension to determine the elements used in residents' satisfaction was overall housing design and size, explaining 10.015% of the variance. According to the factor loadings, elements of this factor are the size of the house, housing design in relation to your daily life, and the number of bedrooms.

The least important dimension was the yard which included its size and layout. The variance explained by this factor was 5.907%. This analysis shows that three main important factors for residents' response to evaluate their satisfaction with their housing conditions in PPR Seri Aman are distance to neighbourhood facilities, common housing area and privacy, and sleeping area in dwelling unit features. It implies that these three factors are the primary residential characteristics that determine the residential satisfaction of the residents in PPR Seri Aman. This finding is supported by Huang and Du (2015) which concluded that neighbourhood characteristics, public facilities and housing characteristics were the main sources to determine the residents’ satisfaction towards their housing. Besides that, as Ibem and Amole (2013) mentioned, satisfaction with the neighbourhood was one of the primary determinants in housing satisfaction. Hence, these elements were crucial to be examined in the residential satisfaction in PPR housing.

Table 10 : Factor analysis of components of satisfaction variables in PPR Seri Aman

|

Residential attributes |

Factot Loding |

Eigenvalue |

% of |

|

|

Variance Cum % |

||||

|

Factor 1: Distance to Neighborhood Facilities |

|

4.783 |

18.395 |

18.395 |

|

Distance to Clinic or Hospital |

0.837 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Shopping |

0.811 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Market |

0.777 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Support Services |

0.760 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Nearest Town Centre |

0.655 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Work Place |

0.600 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to School |

0.506 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Religion Locations |

0.484 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 2: Common Housing Area and Privacy |

|

3.585 |

13.790 |

32.185 |

|

Size and Layout of Bathroom 2 |

0.791 |

|

|

|

|

Size and Layout of Kitchen |

0.760 |

|

|

|

|

Size and Layout of Bathroom 1 |

0.759 |

|

|

|

|

Level of Privacy |

0.608 |

|

|

|

|

Size and Layout of Living Area |

0.554 |

|

|

|

|

Dining Space |

0.540 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 3: Sleeping Area |

|

3.197 |

12.297 |

44.481 |

|

Size and Layout of Bedroom 2 |

0.816 |

|

|

|

|

Size and Layout of Bedroom 3 |

0.726 |

|

|

|

|

Size and Layout of Master Bedroom |

0.640 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 4: Management of Housing Area |

|

2.932 |

11.277 |

55.759 |

|

Availability of Parking |

0.848 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Take Public Transport |

0.801 |

|

|

|

|

Traffic Nearby |

0.741 |

|

|

|

|

Distance to Playground |

0.686 |

|

|

|

|

Sidewalks and Connectivity of Paths Safety |

0.518 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 5: Overall Housing Design and Size |

|

2.604 |

10.015 |

65.773 |

|

Size of House |

0.508 |

|

|

|

|

Housing Design Related to Daily Life |

0.701 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Bedrooms |

0.503 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 6: Yard |

|

1.536 |

5.907 |

71.680 |

|

Size and Layout of Yard |

0.530 |

|

|

|

Relationships between residents’ Satisfaction and their Socio-cultural characteristics .

Table 11: Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) matrix between residential satisfaction components and socio-cultural characteristics of respondents.

|

Variables |

Gender |

Age |

Ethnic |

Religious |

Length of Residency |

Household Size |

Education Level |

|

Factor 1 |

.206* |

|

|

|

.359** |

|

-.225* |

|

Factor 2 |

|

|

-.243* |

-.286** |

|

-.221* |

|

|

Factor 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.214* |

|

Factor 4 |

|

-.213* |

|

|

|

|

.392** |

|

Factor 5 |

|

|

.269** |

.253* |

|

|

|

|

Factor 6 |

|

|

-.209* |

-.225* |

|

|

|

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Using Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), this section examines the relationship between residents' socio-cultural background and their degree of satisfaction with the elements of housing necessity. In Table xx, Pearson's r varies between +1 (perfect positive correlation) and -1 (perfect negative correlation). It determines that there is a relationship between the two elements.

Satisfaction with distance to neighborhood facilities tends to correspond with residents' gender and duration of the residency positively. In contrast, the same factor leads to a decrease in their education level. Residents' satisfaction with common housing areas and privacy negatively correlated with residents' ethnic, religious, and household size. This result is supported by Mohamad (1992) that the housing area compartmentalized into different activities area is completely unfamiliar to Malay culture.

Moreover, he also concluded that housing units are unsuitable for anyone because the rooms' spatial relationships directly contrast to the three cultures' living patterns. Furthermore, the relationship between privacy and residential satisfaction is also supported by Rahim (2015) which stated that visual privacy is a crucial component and consideration for Muslim homes. However, it contradicts the study done by Abdu et al. (2014), which indicated a positive correlation between household size and residential satisfaction. This current finding implies that the larger the household size, the lower the satisfaction in the common housing area. This study’s finding suggests that the length of residency had a positive relationship with residential satisfaction. It was contrary to Abdu et al. (2014), who found no significant correlation between length of residence and residential satisfaction. The current finding indicates that the longer the residents’ length of stay in PPR, the higher the residential satisfaction level.

Furthermore, respondents' education level is positively correlated with satisfaction with the sleeping area. Management of housing area satisfaction index negatively correlates with respondents' age, whereas the same factor has a positive relationship with education level. Satisfaction with overall housing design and size are positively associated with both residents' ethnicity and religious. This result is supported by Yap and Lum (2020) which the different ethnic groups were considered the various elements of Feng Shui in their housing internal arrangement and design. On the other hand, about the correlation between educational level and residential satisfaction, the finding contradicts the study done by Abdu et al. (2014), which found that educational level had no relationship with residential satisfaction. However, Abdu et al. (2014) supported this finding that age was negatively associated with residential satisfaction. It means that the older residents were more satisfied with the housing compared to the young residents. However, the yard satisfaction score is negatively correlated with both residents' ethnicity and religious.

In summary, it concluded that the residents' socio-cultural characteristics such as gender and length of residency are positively related to residential satisfaction. At the same time, age and household size have a negative correlation with residential satisfaction. Other characteristics such as ethnic, religious and education level are positively and negatively associated with residential satisfaction. These findings conclude that different residents' socio-cultural characteristics have their own indicators to express their satisfaction in housing. These characteristics are the factors to consider in determining residential satisfaction.

Conclusion

According to the responses from 93 residents in PPR Seri Aman, it was found that the top three main factors for residents' response to evaluate their satisfaction with their housing conditions are distance to neighborhood facilities, common housing area and privacy, and sleeping area in dwelling unit features. It concludes that these elements are necessary to include in the residential satisfaction assessment. From the factor analysis, these six factors were used to examine the different socio-cultural characteristics influencing the level of satisfaction of owners in terms of housing necessity. The research findings showed that socio-cultural characteristics such as gender and stay duration are positively related to residential satisfaction. In contrast, age and household size have a negative correlation with residential satisfaction. Other characteristics such as ethnic, religious, and education level are positively and negatively associated with residential satisfaction.

Thus, this research proved that the seven different socio-cultural backgrounds of the residents in PPR low- cost housing were related to their residential satisfaction. The study revealed that to improve residential satisfaction, it needs to consider socio-cultural and housing characteristics, especially in Malaysia, because other ethnic groups from diverse backgrounds live in low-cost public housing.

For futher recommendation, this research has evaluated two aspects from dwelling unit features and neighborhood facilities. Although there were many in the assessment of low-cost housing, there is still a lack of evaluation of other elements. Therefore, it is suggested that future research consider other relevant factors such as management, maintenance services, quality of the building, and quality of residents' lifestyle from the perspective of the residents and other professionals by comparing standard guidelines in Malaysia and other countries.

In addition, the evaluation of residential satisfaction in PPR low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur requires a larger sample size. Hence, it is suggested that future research can survey more PPR housing in other locations to collect more opinions from the different backgrounds of residents. Eventually, the analysis can provide explicit feedback on the latest condition of PPR housing and, therefore, is helpful for future research and development planning.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Department of Quantity Surveying from Faculty of Built Environment (FOBE) TARUC for providing the opportunities to carry out this research area. This research was supported by the Centre for Construction Research, Faculty of Built Environment, Tunku Abdul Rahman University College. The authors also appreciate any constructive comments from reviewers and solely responsible for any mistakes from this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflict of interest

Funding sources

There is no funding sources.

References

- Abdu, A., Hashim, A. H., Samah, A. A., & Salim, A. S. S. (2014). Relationship between background characteristics and residential satisfaction of young households in unplanned neighbourhoods in Kano, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19(10), 138-145.

CrossRef - Agus, M. R. (1997). Historical perspective on housing development. Housing the nation: a definitive study, 33.

- Andersen, H. S. (2011). Explaining preferences for home surroundings and locations. Urbani izziv, 22(1), 100-114.

CrossRef - Anuar, M. F. B., & Ramele, R. B. (2017). Built Environment.

- Asiyanbola, R., Raji, B., & Shaibu, G. (2012). Urban liveability in Nigeria-A pilot study of Ago-Iwoye and Ijebu-Igbo in Ogun State. Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering. B, 1(10B), 1203.

- Awotona, A. (1990). Nigerian government participation in housing: 1970–1980. Habitat international, 14(1), 17-40.

CrossRef - Aziz, A. A., Ahmad, A. S., & Nordin, T. E. (2012). Vitality of Flats Outdoor Space. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 36, 402-413.

CrossRef - Azmi, D. I., & Karim, H. A. (2012). A comparative study of walking behaviour to community facilities in low-cost and medium cost housing. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 35, 619-628.

CrossRef - Baker, E. L. (2002). Public Housing Tenant Relocation: Residential Mobility, Satisfaction, and the Development of a Tenant's Spatial Decision Support System.

- Bakhtyar, B., Zaharim, A., Sopian, K., & Moghimi, S. (2013). Housing for poor people: a review on low-cost housing process in Malaysia. WSEAS transactions on environment and development, 9(2), 126-136.

- Bennett Peter, D., & Kassarjian Harold, H. (1972). Motivation and personality. Consumer Behavior.

- Brooks, L. M. (1939). PERRY. Housing for the Machine Age (Book Review). Social Forces, 18(1), 291.

CrossRef - Ishak, S.N.H, Mohamad Thani, T & Low, E.D. (2018). A Study On Space Design Criteria For Affordable Housing In Klang Valley, Malaysia. Journal of Built Environment, Technology and Engineering, 4, 82-98.

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Chen, L., Zhang, W., Yang, Y., & Yu, J. (2013). Disparities in residential environment and satisfaction among urban residents in Dalian, China. Habitat International, 40, 100-108.

CrossRef - Chohan, A. H., Che-Ani, A. I., Shar, B. K., Awad, J., Jawaid, A., & Tawil, N. M. (2015). A model of housing quality determinants (HQD) for affordable housing. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 20(1), 117.

- Construction Industry Development Board Malaysia (2019), Rethinking affordable housing in Malaysia: Issues and challenges, Construction Industry Development Board Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

- De Chiara, J. & Koppelman, L. (1929), Urban planning and design criteria, Litton Von Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York

- Djebuarni, R., & Al-Abed, A. (2000). Satisfaction level with neighbourhood in low- income public housing in Yemen. Property Management, 18(4), 230–242.

CrossRef - Dzulkalnine, N., Hamid, Z. A., Ibrahim, I., Zain, M. Z. M., Kilau, N. M., Musa, I. D., & Rahman, M. F. A. Moving towards Smart Cities: Assessment of Residential Satisfaction in Newly Designed for Public Housing in Malaysia.

- Economic Planning Unit (2010), Tenth Malaysia plan 2011-2015, Prime Minister's Department, Putrajaya.

- Goh, A. T., & Yahaya, A. (2011). Public low-cost housing in Malaysia: Case studies on PPR low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur. Journal of Design and Built Environment, 8(1).

- Ha, S. K. (2008). Social housing estates and sustainable community development in South Korea. Habitat international, 32(3), 349-363.

CrossRef - Hashim, A. E., Samikon, S. A., Nasir, N. M., & Ismail, N. (2012). Assessing factors influencing performance of Malaysian low-cost public housing in sustainable environment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 50, 920-927.

CrossRef - Huang, Z., & Du, X. (2015). Assessment and determinants of residential satisfaction with public housing in Hangzhou, China. Habitat International, 47, 218-230.

CrossRef - Ibem, E. O., & Amole, D. (2013). Residential satisfaction in public core housing in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Social indicators research, 113(1), 563-581.

CrossRef - IBM (2014), SPSS Statistics: KMO and Bartlett's Test. Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/23.0.0?topic=detection-kmo-bartletts-test

- Karim, H. A. (2012). Low cost housing environment: compromising quality of life?. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 35, 44-53.

CrossRef - Kuala Lumpur City Hall (2008), Kuala Lumpur structure plan 2020, KLCP-2020.pdf

- Kumar, R. (2018). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage.

- Leong, KC (1979), ‘Low cost housing design’, in Public and private housing in Malaysia, eds Tan, SH & Sendut, H, Kuala Lumpur: Heinemann Educational Book (Ltd), Kuala Lumpur.

- Lu, M. (1999). Determinants of residential satisfaction: Ordered logit vs. regression models. Growth and change, 30(2), 264-287.

CrossRef - Makinde, O. O. (2014). Influences of socio-cultural experiences on residents’ satisfaction in Ikorodu low-cost housing estate, Lagos state. International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development, 5(3), 205-221.

CrossRef - McCray, J. W., & Day, S. S. (1977). Housing values, aspirations, and satisfactions as indicators of housing needs. Home economics research journal, 5(4), 244-254.

CrossRef - Merriam, S. B. (2001). How Research Produces Knowledge. In J. M. Peters & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Adult Education (pp. 42–65). Lanham, MD: Jossey-Bass.

- Ministry of Housing and Local Government (1998), Buletin perangkaan perumahan 1998, Percetakan Nasional Berhad, Kuala Lumpur.

- Ministry of Housing and Local Government (2002), Buletin perangkaan perumahan 2000, Percetakan Nasional Berhad, Kuala Lumpur.

- Ministry of Housing and Local Government Malaysia (2011), Housing in the new millennium - Malaysian perspective, Ministry of Housing and Local Government Malaysia, Putrajaya. Retrieved from https://ehome.kpkt.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/297.

- Mohamad, R. (1992). Unity in diversity: an exploration of the suports concept as a design approach to housing in multi-ethnic Malaysia (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Mohd-Rahim, F. A., Zainon, N., Sulaiman, S., Lou, E., & Zulkifli, N. H. (2019). Factors affecting the ownership of low-cost housing for socio-economic development in Malaysia. Journal of Building Performance, 10(1), 1-16.

- Mohit, M. A., & Raja, A. M. M. A. K. (2014). Residential satisfaction-concept, theories and empirical studies. Planning Malaysia, (3).

CrossRef - Mohit, M. A., Ibrahim, M., & Rashid, Y. R. (2010). Assessment of residential satisfaction in newly designed public low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Habitat international, 34(1), 18-27.

CrossRef - Morris, E. W., Crull, S. R., & Winter, M. (1976). Housing norms, housing satisfaction and the propensity to move. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 309-320.

CrossRef - National Property Information Centre (2018). Mismatch between demand & supply of affordable housing, National Property Information Centre, Putrajaya.

- Ogu, V. I. (2002). Urban residential satisfaction and the planning implications in a developing world context: The example of Benin City, Nigeria. International planning studies, 7(1), 37-53.

CrossRef - Ozo, A. O. (1990). The private rented housing sector and public policies in developing countries: The example of Nigeria. Third World Planning Review, 12(3), 261.

CrossRef - Parker, C., & Mathews, B. P. (2001). Customer satisfaction: contrasting academic and consumers’ interpretations. Marketing intelligence & planning.

CrossRef - Plan, K. L. S. (2020). Community Facilities. Community Facilities. City Hall Kuala Lumpur. Retreived from: http://www. dbkl. gov. my/pskl2020/english/preface. htm.

- Rahim, Z. A. (2015). The influence of culture and religion on visual privacy. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 170, 537-544.

CrossRef - Rani, W. N. M. W.M. (2013). Understanding The Usage Pattern Of Local Facilities In Urban Neighbourhood Towards Creating A Livable City. Proceeding of International Workshop on Liveable Cities (IWLC) 2013, 472-487.

- Ross, C. E. (2000). Walking, exercising, and smoking: does neighbourhood matter?. Social Science & Medicine, 51(2), 265-274.

CrossRef - Salleh, A. G. (2008). Neighbourhood factors in private low-cost housing in Malaysia. Habitat International, 32(4), 485-493.

CrossRef - Shuid, S. (2008, January). Low income housing provision in Malaysia: the role of state and market. In 5th Colloquium of Welsh Network of Development Researchers (NDR), Newtown Wales, United Kingdom.

- Sufian, A., & Rahman, R. A. (2008). Quality housing: regulatory and administrative framework in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics and Management, 2(1), 141-156.

CrossRef - Sulaiman, F. C., Hasan, R., & Jamaluddin, E. R. (2016). Users perception of public low income housing management in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 234, 326-335.

CrossRef - Sulaiman, N., Baldry, D., & Ruddock, L. (2005, January). Can Low Cost Housing in Malaysia Be Considered as Affordable Housing. In Proceeding of the European Real Estate Society (ERES) Conference 2005 (pp. 14-18).

- Tan, S. H. (1979). Factors influencing the location, layout and scale of low-cost housing projects in Malaysia. Public and Private Housing in Malaysia, 67-90.

- The Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (2021) Affordable Home Scheme. Retrieved from https://www.malaysia.gov.my/portal/content/30704

- Yap, J. B. H., & Lum, K. C. (2020). Feng Shui principles and the Malaysian housing market: what matters in property selection and pricing?. Property Management.

CrossRef - Yockey, R. D. (2016). SPSS demystified: a simple guide and reference. Routledge.

CrossRef - Zaid, N. S. M., & Graham, P. (2011). Low-cost housing in Malaysia: A contribution to sustainable development. Proc., Energy, Environment and Sustainability, 82-87

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.