Blacks in the Middle Ages What About Race and Racism in the Past? Literary and Art-Historical Reflections

1University Distinguished Professor,, Department of German Studies, University of Arizona, LSB Tucson, Arizona U. S. A .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.6.1.04

Undoubtedly, racism is a deeply-anchored problem that continues to vex our world. There is a long history behind it, which can easily be traced back to the Middle Ages and beyond. This article, however, takes into consideration a number of medieval narratives and art works in which surprisingly positive images of Blacks are provided. The encounter with black-skinned people tended to create problems even for the best-intended white intellectuals or poets during the pre-modern era, but the examples studied here reveal that long before the modern age there was already an alternative discourse to embrace at least individual Blacks as equals within the courtly and the religious context. Since Europe did not yet know the large-scale form of slavery, as it emerged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there were much less contacts between Blacks and Whites. Nevertheless, the evidence brought to the table here clearly signals that we would commit a serious mistake by equating modern-day racism with the situation in the Middle Ages, as much as modern research (Heng) has argued along those lines. It would be more appropriate to talk about the encounter of races within the literary and art-historical context. Even the notion of Black diaspora would not fully address the issue because the evidence brought to the table here engages mostly with black or half-black knights and other individuals who enjoy considerable respect and appear to be integral members of courtly society both in the East and in the West. Instead of working with theoretical models developed for the analysis of racism in our own times, such as Critical Race Theory (CRT), this study offers close readings of literary examples of personal encounters between members of different races in medieval German and Dutch literature, and of the representation of Blacks in late medieval and early modern art history, concluding with some comments on the first Black philosopher in eighteenth-century Germany.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Classen A. Blacks in the Middle Ages – What About Race and Racism in the Past? Literary and Art-Historical Reflections. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2023 6(1). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.6.1.04

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Classen A. Blacks in the Middle Ages – What About Race and Racism in the Past? Literary and Art-Historical Reflections. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2023 6(1). Available here: https://bit.ly/3MuEQsA

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 04-02-2023 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 05-04-2023 | |

| Reviewed by: |

Kendric L. Coleman

Kendric L. Coleman

|

|

| Second Review by: |

Faith S. Wambui Kariuki

Faith S. Wambui Kariuki

|

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr Jyoti Atwal | |

Introduction

The recent years have witnessed an explosion of heated discussions about racism not only in our day and age, but also in previous centuries, in fact, going as far back as the Middle Ages. It seems as if currently every cultural, literary, philosophical, artistic, musical, even scientific aspect is re-examined with respect to its racist roots and character. Both from a theoretical and a practical perspective, this departure in research and also in political activism has certainly positive consequences since it forces us all to reflect once again upon the basic resources we rely on in our research and on the theoretical models that we embrace to carry out that research. Most dramatically, perhaps, the entire work of William Shakespeare (1564–1616) has become the subject of critical, at times acrimonious investigations driven by Critical Race Theory (CRT) (cf. now Dadabhoy and Mehdizadeh 2023; for the role of Blacks in Renaissance England, see Earle and Lowe, ed., 2005). Unfortunately, CRT itself has become highly politicized, or is a political issue at current times bitterly fought over by the left and the right.

Racism seems to lurk everywhere as soon as we lift the veil of many of the pre-modern documents, as numerous scholars have recently argued (Lindsey 2018; Crenshaw, ed., 2019). Hence, we would need to ask ourselves once again why there is such an apparently universal need among people to marginalize, repress, and mistreat minority groups, or to make one section of the population, such as women, to a secondary class (Walcott 2014)? Both religion and racism, gender conflicts and social antagonism always appear to be at play in this universal conundrum of humanity (Opitz 1992). And then there is also the need for a scapegoat, a universal tendency always to blame a minority for whatever the majority considers as a threat, embarrassment, or its own failure, as expressed extraordinarily well by the Swiss writer Max Frisch in his play Andorra from 1961 (Frisch 1961). Fear and the absence of rationalism, lack of trust, and the rejection of ancestral family members within the global human community are some of the critical factors in this entire phenomenon (Ekotto 2023; she engages, above all, with James Baldwin in his conversation with Margaret Mead; Baldwin 1971). As Jonathan Hsy now argues, many minority groups across the world are actually turning to the medieval past to fight modern-day racism (Hsy 2021), which adds a rather curious twist to the issue to be discussed here. And as Margo Hendricks emphasizes, the investigation of pre-modern racism or concepts of race allows us to recognize better the current discourse and to prepare ourselves for the future (Henricks 2021).

One of the most recent issues of German Quarterly (Layne and Thurman 2022) was dedicated to the discussion of racism in the history of German literature, but the medieval and early modern period was entirely left out. Was there no racism then? This rhetorical question can easily be answered with a resounding ‘no,’ there was racism, of course, but the real issue is what the relevant sources or documents can tell us about the relationship between Christian white Europeans (complete dominance, of course), and Blacks in those societies. The placement of Blacks in Africa and their negative evaluation goes back, as we all know, to the Old Testament (Braude 1997), so the pre-modern period, in its Christian framework, was racist from the beginning, although the New Testament argued pretty much the opposite way. Altogether, we might be best advised to use the term ‘racism’ with caution when we reflect upon the pre-modern age, and then investigate more carefully examples of encounters between black and white people. Nevertheless, I would still insist that we can find traces, if not strong elements of racism already in the post-Roman period, i.e., the Middle Ages (Rambaran-Olm and Wade 2022).

As Dorothy Kim formulates in the introduction to a special issue of Literature Compass,

The story of premodern critical race cannot and should not be written without Black, indigenous, and people of color, without asking question about the experiences, ideas, or history of the racially-marked people of the premodern past. “It is not only nonsensical but also unethical to continue” to discuss race without asking what that meant to the racialized bodies of this premodern past (echoing Johnson). Race is not a theoretical abstraction; race is not an intellectual debate. Race has a body count. Race is political. Race matters now and race matters in the premodern past (13).

What this argument entails, and what many younger scholars seem to demand, would be to identify a black voice in the Middle Ages and to listen to him/her, which would thus provide some equality in the discourse on race. Such a voice, however, does not exist, and we are limited to narrative by white Europeans who commented at times on black people and/or integrated Blacks as protagonists.

Undoubtedly, while the western world has progressed a lot over the last century or so and tries hard to distance itself from its racist past, especially among modern scholars, racism is alive and well today, as experiences in every sector of our society (USA) tragically demonstrate, whether in our schools or in the streets with racist police offers hunting down and killing innocent black people, at least in the worst-case scenarios, whether in our political system or in the legal courts. Racism is also present in other (if not all) parts of the world, sometimes directed against Whites, Asians, Natives, and sometimes against other ethnic groups. We could even reach the frustrating conclusion that it constitutes one of the inherent problems in all of human life so desperately in need of finding one’s own identity by means to distancing oneself from others by racist and other pejorative strategies.

Understandably, there is much anger among the affected and targeted social or ethnic groups about institutionalized racism, often embedded also in our literary canon until today. However, as this brief article will demonstrate, we have to be careful not to throw the proverbial baby out with the bath water and become overly obsessed with reading every historical or literary document through that lens, as if racism has always been the all and only issue relevant for the critical reading of a literary text or art work. It would amount to a political decision to place the investigation of racism, which was certainly in place also in the past, if not even more so than today, up front before all other issues.

The present, certainly highly necessary fight against racism should not mislead us to equating modern forms of racism with parallel phenomena in the past, as similar as they often might appear to be. Moreover, we need to be aware about the specific differences between racism as an observable ideology across social classes, genders, and age groups in modern society, and the rather unexpected forms of relatively open-minded relationships between the races as described in some art works and literary texts from the Middle Ages. This epithet, ‘open-minded,’ might be questioned by some critics, but we would not pursue an appropriate or fair path of investigation if we cast everything in the same category as racist just because a black person is presented somewhere in art or literature in negative or simply neutral light. As we will observe, counter to many modern assumptions, numerous medieval poets and artists felt no hesitation to incorporate black characters into their works and to give them relatively full credit or acknowledgment (Collins and Keene, ed., 2023). What this all might entail regarding racism, remains a highly complex issue, but if we examine the concrete data available to us in texts and images, we should be able to discriminate further and to gain a more objective perspective. As this article intends to demonstrate, pre-modern poets and artists paid considerable respect to Blacks and did not simply cast them in racist categories, as is often the case particularly in the modern age.

Theoretical Problematics

However, we have to be very careful with our terminology which can be extremely slippery, particularly because the ideological battle over this bad issue has reached a superheated pitch in current politics. Teaching of CRT in public schools has been banned in numerous US states (especially in Florida), many conservative politicians appear to be deeply scared of allowing public libraries to hold and lend books in which the history of racism is being taught (Burmester and Howard 2022). At the same time, we observe a trend toward mass incarceration in the USA, which predominantly affects Black Americans (Alexander 2010/2020; Stovall 2021). All those ideological, political, and economic battles are very much on the minds of current scholarship and are part of intensive public debates, but if we want to approach the issue, we must embrace the principle of sine ira et studio to be fair and open-minded toward the relevant sources containing important data for our investigation. We definitely need also a historical perspective to understand the phenomena as they matter today. As numerous scholars have already alerted us, ‘racism’ does not only pertain to the conflict between people with different skin colors. It also entails the general process of marginalizing and repression entire sections of the population, such as Jews and Muslims within a predominantly Christian society, as we can observe vividly in medieval Spain, for instance (Morera 2022; cf. also Hund 2017). The critical question pertains to the officially supported presentation of public images in art and literature, for instance, and hence to the hidden agenda by the authorities determining the dominant culture at a certain period (Patton, Perry, and Heng 2019). Geraldine Heng had outlined her project of investigating race in the Middle Ages as follows:

The Invention of Race works to retrieve the economic and social relations between ethnoracial groups; grasp the politics of international war, colonizing expeditions, and commercial trade; unravel the meaning of iconic artifacts or phenomena – such as the baffling statue of a black African St. Maurice in Germany or Marco Polo’s mercantile gaze on the races of the world – or calibrate from eyewitness and other accounts the West’s understanding of global ethnoracial relations in macrohistorical time. (Heng 2018, 6)

She offers an extensive discussion of Blacks in literature and the arts of the Middle Ages and reaches this conclusion:

Unsurprisingly, black Africans who appear in twelfth and thirteenth century European literature – especially the heroic epics and romances that are the staple narratives depicting martial encounter – are often rendered as Saracens or heathens, this formulation becoming something of a literary commonplace. (193)

I can only defer to her impressive work as the groundbreaking study in this field and continue to study a number of examples she has already included in her investigations that both confirm and also contradict her observations. I hope thereby to diversify the discourse on this topic further and bring more relevant material to the table so that we can, perhaps, defuse or depoliticize the entire debate on racism and literature and the arts especially in the pre-modern world.

Outline

The first step will be to acknowledge that in the Middle Ages, the public discourse about race was rather different than what we might conceive of it today, especially because in very practical terms most Christian Europeans had either very little or no experiences with non-white people. Then, I will examine several major literary texts where blackness suddenly matters, but not in explicit racist terms. Finally, I want to bring to our attention several significant art works that shed important light on this topic and that force us to discriminate the entire debate considerably. It would far from me to try to whitewash (pardon the pun) the Middle Ages of racism, but the situation as described by various poets and as depicted by various artists was more complex than has often been assumed (Heng 2018, offers impressively critical comments and deserves much respect for her close reading of some of the narratives that I will address as well). The intellectual conundrum rests in the issue whether we can draw direct lines of connection between medieval race awareness and modern-day racism, and hence whether all those forms of hatred, including Antisemitism or Islamophobia, follow the same pattern throughout history, or whether we must distinguish between cultures and periods (Eliav-Feldon, Isaac, and Ziegler, ed., 2009).

There is also the danger that we accept certain data concerning the treatment of minority groups as the all-determining ones, which would blind us to alternative voices or images. Considering the large number of relevant studies addressing these issues, we can firmly conclude that those matter centrally today and hence need to be discussed from many perspectives (for a partial bibliography, see Hsy and Orlemanski, ed., 2017). In this regard, the Middle Ages deeply matter for us today because if we can discover the roots of racism in that age, then we would have a consistent line of argument available concerning its historical evolution. Tackling racism at its roots would hence empower the present generation of readers or scholars to address it constructively, and from a deep perspective. What seems most worrisome then, would be the observation that racism appears to be the outgrowth of fundamental human tendencies to divide society into a majority and a minority group, to marginalize the latter, and to repress them by way of developing racist concepts (Mellinkoff 1993). I venture already here to question this assumption which threatens to flatten all historical epistemology and denies human ability to grow, or to evolve, and thus also to overcome racism (Ramey 2014; Hund 2017).

Subsequently, hence, I propose to take a more discriminating approach and to draw on several literary documents and some art works where Blacks appear as relatively equal members of the court next to the white courtiers.

Of course, the evil black knight

In the rather odd Occitan romance, Blandin de Cornoalha (ca. second half of the thirteenth century), recently edited and translated by Margaret Burrell and Wendy Pfeffer (2022), we encounter also a black knight, whose appearance is obviously modelled after many other opponents in previous romances. Intriguingly, the first time we hear of him a messenger informs one of the protagonists, Guilhot, at least indirectly, that the other man is a worthy good warrior (l. 656); and naturally, Guilhot wants to fight against him but the messenger warns him that all other knights who had tried their luck in such a joust had failed and had died at the black knight’s hands – clearly an allusion to similar themes in Chrétien de Troyes’s Erec and Yvain, and also in the Welsh Owein, for instance (Pfeffer 2022, 64; she also refers to the Black Knight in Jaufre). Subsequently, Guilhot enters the wasteland where the future opponent resides and protects his orchard from foreign intruders, and after a short angry exchange with the black knight, the two men fight bitterly all day long. At one point, both are so exhausted that they have to sit down and rest, but only to resume their battle until their swords break and they resort to their knives.

Although Guilhot bleeds profusely, he finally manages to stab the Black Knight through the neck which then kills him. Interestingly enough, while the latter lies on the floor, about to exhale, he bags Guilhot to fetch him some water to drink from the pond. The latter happily complies and does not voice any negative opinions about the dying knight whom he actually treats with great respect in that situation. In fact, once the Black Knight has died, the narrator comments: “de que Guilhot fut mot dolent” (776; for which Guilhoc was most sad). He appeals to God to grant mercy and forgiveness to the dead man (77–82) and then throws the corpse into the fishpond because he does not want any animal to eat the body.

But not enough with these few comments, Guilhot rides off, himself badly wounded, and is welcomed and treated by a hermit who wonders about his severe injuries. The answer sheds significant light on the Black Knight since he is identified as “un noble cavllier apert” (805; There was a noble knight). The hermit is pleased to hear that news because too many other knights had been killed in their battles against the by now dead man, but he also identifies him as the member of a worthy noble family: “So era hom de gran corage / et atressis de gran lingnage” (817–18; He was a man of great valor / and likewise of a good family). The hermit then warns Guilhot to be on his guard because the Black Knight’s family members might avenge his death. To provide him with a safeguard, the hermit urges Guilhot to stay in his humble abode, where he recovers completely. Later, as soon as he has left, he encounters the Black Knight’s brother who deeply laments the latter’s death, and both then fight against each other, with Guilhot being victorious again, killing the brother as well.

But was he really a black man, like his brother. The narrative specifies that he was “un cavaler armat de negre” (861; a knight armed in black) but does not say anything about his skin color or race. Of course, Guilhot has to face both brothers, one after the other, and subsequently a whole band of knights who all try to capture him. At the end, they defeat him and take him to a prison (981), from where his friend, Blandin, later has to liberate him, which does not concern us here any longer. The first reference to the Black Knight, however, is not limited to his armor as in the case of the brother, and yet there are no indications that the narrator would have viewed his blackness in any negative terms. He is simply a formidable opponent whom Guilhot has to overcome and kill in order to prove his own knightly prowess. In fact, Guilhot would have done the same thing with any other enemy, irrespective of the skin color. What matters here only is the fact that the Black Knight is a major challenge, and by overcoming him, Guilhot’s fame grows considerably, which is a basic principle of most courtly romances.

Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival

There are many reasons to study this major Grail romance composed in Middle High German sometime around 1205, based in part on Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval (ca. 1180). For our purposes, there is one unique episode which has already attracted much attention by Germanists (for critical summaries of the relevant research, cf. Bumke; Hartmann), but also by scholars such as Heng (2018) focusing on racism in the pre-modern world. Gahmuret, Parzival’s father, though a most outstanding knight who cannot be defeated unless magic is involved, which ultimately leads to his death, is a strangely unreliable, highly selfish individual. He seems not to be bound to any social commitments, and even love, marriage, and fatherhood do not seem to matter much to him. All that matters to him proves to be knighthood in which he excels extremely.

Significantly, Gahmuret does not care about Christianity as such, as much as he later pretends to his wife Belacane that their differences in faith was the main cause for his leaving her. He is not attached to any national, political, or dynastic entity, and he serves whoever might need him. In a way, we might call him already a global citizen in the Middle Ages, although in this context it might be regarded as a negative (e.g., Hermans, ed., 2020; Borgolte 2022; Baumgärtner, forthcoming). As the narrator informs us, Gahmuret gains fame both “in Morocco and in Persia. His hand took such toll elsewhere, too – in Damascus and in Aleppo, and wherever knightly deeds were proffered, in Arabia and before Araby” (Wolfram, trans. Edwards, 8–9).

At one point, Gahmuret also reaches a kingdom somewhere in the East where an unmarried black queen, Belacane, is under the heavy siege of a hostile prince. Gahmuret, although abhorred about her black skin at first, then decides to help her; he overcomes the enemy, liberates the city, and then falls in love with the queen, with whom he will later have a son, though by that time he has already left again, in his typical fashion of not letting any person tie him down to marriage or any other commitment.

Reading the narrator’s comments carefully, we discover many significant perspectives toward this black person. She rules over the kingdom of Zazamanc and had been wooed by the knight Isenhart who tragically then died fighting to defend her, which all citizens mourn deeply. Out of his desire to prove his love for Belacane, Isenhart had jousted against another knight without wearing armor, which led to his death. His friends and relatives blame Belacane for this tragic outcome and destroy her kingdom in revenge, until Gahmuret appears and defeats the completely (Brüggen and Bumke 2011, 887–88).

The further details do not concern us here, which have been discussed already many times by Wolfram scholars, whereas the narrator’s comments regarding the personal relationship between Parzival’s father and this black queen assume central importance. He characterizes Belacane as “that gentle lady free of falsity” (9), but she is also feisty enough to fend off the enemies, even though with difficulties, which makes Gahmuret’s sudden appearance especially important. Although he is somewhat taken aback by the fact that all the people of Zazamac are black – in their company time seemed to him to pass slowly” (9) – he happily offers to help them for an appropriate remuneration, although he is not in need of any money or gold. Gahmuret orchestrates a splendid entry into the city and notes, as the narrator remarks, that they were all black: “of the raven’s hue was their complexion” (10). Nevertheless, there does not seem to be any cultural difference between the world of a western Christian court and that of Zazamanc, with all the same trappings, norms of behavior, and the political and administrative organization. For instance, “The burgrave of the city then graciously requested his guest not to forbear to press whatever claim he wished upon his property and person” (10). Gahmuret is then invited to kiss the burgrave’s wife, “though he took little pleasure in that” (11), obviously because she is black. Gahmuret displays, however, an arrogant attitude throughout because he knows only too well that he is the best knight anywhere and can demand the global respect which everyone pays him.

At the same time, the narrator paints a most impressive picture of the black queen although she is lacking in the beauty of a “dewy rose” (12). Despite the negative comments about blackness, Belacane is praised for her “womanly feelings” who was “in other respects of courtly disposition” (12). In the subsequent conversation, in which she reveals all her trials and tribulations over Isenhart’s death, she emerges as a most worthy noble lady, so when she concludes: “Now my bashful womanhood has protracted his reward and my suffering” (13). And: “Grief blooms upon my loyalty. I never became wife to any man” (13).

Gahmuret is deeply stricken by Belacane’s beauty, and her blackness suddenly no longer matters to him: “although she was a heathen, a more womanly and loyal disposition had never glided into a woman’s heart. Her chastity was a pure baptism, as was the rain which poured upon her, the flood that flowed from her eyes down upon her sable and her breast. Contrition’s cult was her delight, and true grief’s doctrine” (14). Undoubtedly, love has sunk into both of their hearts, as the subsequent events indicate, leading both to their marriage and sexual union. Blackness no longer matters here at all, and Gahmuret suddenly demonstrates his soft side, feeling bashful and embarrassed when she serves him at a dinner as a sign of her gracious hospitality (16).

Wolfram, however, continues to inject facetious remarks about their racial difference, which cannot be denied altogether, and which plays no real role in their subsequent love-making: “Then the queen practised noble, sweet love, as did Gahmuret, her heart’s beloved. Yet their skins were unalike” (20). However, as soon as all knightly challenges are overcome and there is nothing more to do for him, he cares little about being the new lord of Zazamanc, although love binds him strongly with Belacane:

Yet the black woman was dearer to him than his own life. Never was a woman better shaped. That lady’s heart never neglected to give him good company – womanly bearing alongside true chastity. (24)

Nevertheless, Gahmuret is and remains a womanizer and thus soon chooses an opportunity to sneak away in the middle of the night, leaving behind only a letter addressed to Belacane which scholarship has discussed already many times (see, e.g., Mielke 1992, 41–45, who cites long passages from Wolfram’s Parzival). It is filled with numerous contradictions and feigned complains about her different religion (presumably, Islam) which would make their living together impossible. He pretends that he would feel love pangs forever, but he does not mean it, as all the circumstances indicate. The concluding line tells it all: “Lady, if you’ll be baptized, you may yet win me for your own” (25).

Poor Belacane, with whom the audience is obviously supposed to commiserate, is deeply distraught, but also somewhat angry because she would not have been opposed to baptism: “I would gladly be baptized and live as he would wish” (25). In other words, the two had never discussed that issue, although they both are filled with deep love for each other. Religion is not ever truly at stake here, and the difference in skin color does not play any noteworthy role either, as much as Gahmuret at first had felt some disgust, obviously because of his Christian, white, European background. Love had forged the two together, yet his irrepressible desire for masculine performance and self-affirmation separates them as well.

We only would have to add here that in the last section of the romance, Wolfram has their son, Feirefiz, appear who proves to be worthy Parzival’s equal. Ironically, either out of ignorance or playfulness, the poet describes him as checkered like a magpie because he is the result of a black woman and a white man. Otherwise, however, Feirefiz demonstrates greatest courtly and knightly qualities, and once his half-brother Parzival has redeemed the Grail with the crucial question to King Anfortas, Feirefiz accepts baptism for himself because he wants to marry the Grail maiden, Repanse de Schoye.

Feirefiz is identified both as a heathen (Muslim?) and as a mixed-race person, and yet, nothing matters to the poet, the narrator, and to Parzival and the entire Arthurian and then the Grail court. They all admire him for his knightly prowess, being an equal match to his half-brother; they are stunned by the wealth that he commands and the enormous army he leads, and they find him charming and entertaining, especially when he is so desirous to get baptized which would allow him both to see the Grail and to marry the Grail maiden: “The host laughed much at that, and Anfortas still more” (341). The audience then is also invited to enjoy this hilarious scene, with Feirefiz being prepared to do whatever it might take to allow him to marry Repanse de Schoye, as if baptism were nothing but a barter for love. The splendid half-black knight states: “‘If it helps me against distress, I’ll believe all that you command. If her love rewards me, then I’ll gladly carry out his command. Brother, if your aunt has a a god, I believe in him and in her – I never met with such great extremity! All my gods are renounced!” (342–43).

Again, just in the case with his mother, Feirefiz’s blackness, or mixed race, is not even commented on and disappears from the narrator’s view entirely because Parzival’s half-brother is such a worthy character who deserves full respect. Dynastic interests, religious ideals, ethical concerns, chivalry, knighthood, and the Grail itself dominate the entire final section of Wolfram’s romance. Racial differences are basically irrelevant for him, and we only learn that Feirefiz actually marries Repanse, with whom he then moves back home somewhere in the Middle East, here vaguely specified as India, where she delivers a son, the future famous Prester John (344), but his racial background is not even mentioned, although he would have been a quarter black through his grandmother.

Granted, Wolfram created only a fictional romance, but he can be identified as the most important medieval poet to address the interaction between Blacks and Whites. There are some whiffs of racism, hidden behind some ironic comments, but in essence, Wolfram can be credited with having composed a work astoundingly free of racist ideology, as far as we can tell, even though recent critics such as Heng have tended to argue differently (2018, 194–95, et passim). She tries hard, coming from many different angles, to characterize Wolfram as a racist, so when she claims: “Blackness of skin, plus religion, is what prevents this foreign corner of the world from looking like Europe” (199).

In reality, Zazamanc and Feirefiz’s in India empires are hardly distinguishable from the Arthurian world since the same global values of courtliness and knighthood dominate, and so also the ideal of courtly love. Racism, at least in the modern sense of the word, has no place in this remarkable romance. Consequently, we can agree with Heng’s reading when she comments: “A White Knight of dubious morality, who ends his life in that global outside and never returns, has discovered that the rest of the world looks greatly like Europe, except for its extraordinary wealth, its lack of Christianity, and the presence of black-skinned peoples” (200; for other studies on this phenomenon, see, for instance, Gray 1974; Brüggen 2014).

As Andreas Mielke (1992) has demonstrated by means of his text anthology, throughout medieval (German) literature, we come across some black people, often described as slaves, sometimes as African kings, or as black merchants and administrators. But Wolfram’s efforts truly go far above all those by his predecessors, contemporaries, and successors because he imagined an erotic relationship between a black woman and a white man. The racial dimension, however, quickly falls away altogether and gives room to religious differentiation (Christianity vs. Islam), although Belacane and later her son Feirefiz demonstrate no particular interest in their own faith. She would have converted if she had been asked; he does quickly convert and submits under a baptism because it is the requirement for him to receive the permission to marry the Grail maid. We should also not forget that Wolfram’s Parzival enjoyed enormous popularity, as documented by the vast number of manuscripts and later references to this work, so this romance provided the audiences with powerful role models and ideals. In light of this entire episode with Gahmuret and Belacane, we can thus argue that thirteenth-century German listeners or readers of this text must have embraced a similarly naïve and uncomplicated attitude toward Blacks.

In most other cases, the poets, such as Rudolf von Ems, The Stricker, Hans Vintler, or Konrad von Megenberg, engage with black people in conjunction with references to the biblical text or classical stories, especially the account of Aeneas’s escape from the burning Troy, reaching Carthage where he falls in love with the Queen Dido (Heinrich von Veldeke or Heinrich von dem Türlin). We also hear once of Apollonius of Tyre who has a love affair with a black queen, Palmina, that is, simply a sexual encounter, at first against his own intention, but she can seduce him at night, which causes deep trouble for him back home because his true love, Queen Diomena, discovers the two through a miraculous mirror (Heinrich von Neustadt). While he at first tries to resist the black woman’s seduction, Diomena is deeply enraged that he has this affair with a “schwartzen zigen” (p. 58, 14312; black goat).

The parallels with Wolfram’s Parzival are obvious, but here the narrator adds unusual comments, such as that black women know particularly well how to provide sexual pleasures – certainly a racist remark. At one point, Apollonius is even transformed into a black man, which horrifies him, but ultimately helps him to recover his senses. But at first, he insists on having the privilege of enjoying this affair with the black woman, who has been impregnated by him (14467). The subsequent events are too complicated to summarize them here, and it suffices to conclude that Heinrich also incorporated the same theme, the marriage of a black woman with a white man. The romance outlines in impressive details Palmina’s own life, her character, and individuality. She is self-assured, strong in her actions, and independent in her decision-making.

The fact that Diomena views her as a dangerous competitor and hence puts her down in racial terms does not need to surprise us because she is simply afraid of losing Apollonius as her own husband (Ebenbauer 1984; Birkhan 2001). Apollonius finally leaves his black lady because he wants to see his children again after many years of separation, which she does not like at all, obviously out of fear never to see him again, but she lets him go, which basically turns the narrative entirely away from the world of the moors, as they are called here in a pejorative fashion. Both here and in Wolfram’s work, the woman’s blackness is described in the dialectical formula borrowed from the Song of Solomon 1:4: ‘I am black but beautiful’ (Mielke 1992, 108–14; see now also Hund 2017).

A Black Knight in Medieval Dutch Literature

Medieval poets enjoyed considerable liberty to experiment with all kinds of narrative settings, so it does not really come as a surprise that they also included references to black queens and black knights. A most remarkable case can be observed in the Medieval Dutch Romance of Moriaen (middle of the thirteenth century; for useful introductions, see Darrup 1999; Brandsma, McFadyen, and Leah, 2017; see also the useful summary and commentary online at https://books.openedition.org/ugaeditions/19820?lang=en), which has attracted considerable attention in recent years (Wells 1971; for an edition, see Finet-Van Der Schaaf 2009).

Just as in the case of Wolfram’s Parzival, Moriaen is the product of a mixed-race marriage, that is, of a black-skinned mother (the Queen of the Moors, unnamed) and a white-skinned father (Sir Agloval, knight of King Arthur’s court). The narrator comments with astonishment how dark-skinned this knight is; only his teeth had the color of white (418–27). As in the case of Blandin, even his armor and weapons are black. We meet him early on when he encounters the two knights Lancelot and Walewein and pronounces that he must fight every knight he would come across unless the latter would have answered his question. However, in that situation, he raises that question only later, after Lancelot has managed to separate him from Walewein in their evenly matched joust against each other. The question pertains only to the whereabouts of his father, King Aglovat, who had been engaged with his black mother just as Gahmuret had been with Belacane in Wolfram’s Parzival. Love is hence considered a force that makes people (already in the Middle Ages) ignore racial differences and turns them away from the exterior appearance (body) to the interior (soul).

Lancelot at first worries that the black man might have originated from hell, but since the stranger had appealed to God, he has to dismiss this racist thought, which indicates the true degree to which European mentality was determined by religious concerns about black people whom they obviously could not situate properly. Moriaen is on a search for his father, and since the two other knights cannot help him, he breaks down emotionally, which moves the others deeply. The narrator makes considerable effort to picture Moriaen in his most impressive physique, towering considerably over the other knights (763–75). The most important line in the narrator’s comments proves to be: “Al was hi sward, wat scaetde dat?” (771; Although he was black, that did not matter all). Both in his knightly prowess and his bodily appearance, Moriaen cuts an excellent figure, at least in Lancelot’s and Walewein’s eyes who, after they have overcome the first shock, treat him completely as an equal. He displays the same knightly prowess, he is on a quest for his white father, and he is filled with deep emotions of a noble kind.

This new attitude, however, is not at all the case elsewhere because people flee in great fear when they espy Moriaen whom they equate, again, with the devil (2408–30). There are numerous episodes in which Moriaen’s friends (white) have to resort to trickery to prevent people from running away from them out of fear of the black man, whom they regularly associate with infernal forces. But the friends then move into the Moorish kingdom, where the encounter the usual problems in such cases as described in many other romances of that time period. Agloval and his black bride marry officially, and the wedding lasts an entire fortnight, when Gawain, Lancelot and Perceval depart to be back home for Pentecost. Courtly culture was hence, according to the anonymous Dutch poet, an international phenomenon and was not at all limited to certain racial groups in the West.

Agloval, as a white knight and husband of the Moorish queen, however, stays behind, which does not constitute any problem for the overall design of the romance. Moriaen is not even depicted like Feirefiz as a mixed-race person, instead he is entirely black, which deeply scares people around him when he operates in Christian white Europe. However, as soon as the other knights get to know him, they embrace him as their equal and defend him against the hostility or mistreatment by others. Similarly, in the Moorish kingdom, the white knights operate without encountering any racism against them. So, altogether, as much as the poet mirrored clear examples of racist feelings, those regularly result from religiously driven fear since a black person is commonly identified with the devil. But Moriaen, as a knight, commands most respectful characteristics and seems even to be more powerful and skilled than the white knights.

Just as in Wolfram’s Parzival, Moriaen’s mother is presented in a most dignified and worthy manner, respected as a princess, until she has delivered a child with the father nowhere around. But later, once Agloval has returned and married her officially, she regains her status and thus also becomes completely acceptable to the European audience. As Darrup observes, “the medieval poet allays his audience’s fears, controls its response, and lessens xenophobia by eliminating the character's exotic qualities” (Darrup 1999, 22; cf. also DeWeever 1990, 529, on whom Darrup relies herself). The very opposite exists in medieval German literature as well, such as the highly negative, racist depiction of a black king in the army of the Muslim ruler Marsilie in Spain, Cernubiles, as described by Priest Konrad in his Rolandslied (Tinsley 2011, 75). But both there and in the Dutch romance, there is a clear sense of Europe being a continent really only at the margin, and that there are many peoples of different races. Whereas Konrad viewed this with great alarm and pushed that aside with the help of a glorious victory brought about by Charlemagne after Roland’s death, the Dutch poet of Romance of Moriaen took a definite step forward in rejecting this traditional racism by portraying the protagonist, in his blackness, as an innocent victim of people’s terrible prejudice, and this despite his glorious chivalric qualification and ethical ideals that make him to a shining example of a knight compared to those extraordinary heroes as Lancelot or Walewein.

In the Old French Chanson de Roland, the Muslim forces also consist of a contingent of black people: “they are large-nosed and broad-eared / and are altogether more than fifty thousand” (Duggan and Rejhon, trans., 2012, The Oxford version, laisse 143, 1917–19). The narrator emphasizes, as was typically in the Middle Ages, that they “are blacker than ink – / all that is white is their teeth” (laisse 144, 1933–34). Since they fight on the ‘wrong’ side of history, against the Christian warriors, they are, of course, the accursed people” (laisse 144, 1932). One of the worst is Abisme, “the most vicious in his company” (laisse 125, 1632), who is characterizes as purely evil, which finds its external expression in his skin color: “he is black as melted pitch” (laisse 125, 1635). But neither the Old French nor the Middle High German version of this chanson de geste serves well to identify specifics of medieval racism, as obvious as it proves to be here. Both poets relied on strong binary opposites, here the good Christian Franks, there the evil Muslims, or Saracens, many of whom are marked by their dark or black skin color. There is no black warrior in Roland’s rearguard or in Charlemagne’s army since both texts served explicitly nationalistic (French) or religious (German) purposes (cf. Bancourt 1982).

Blacks in Medieval Manuscript Illuminations

King Alfonso X el Sabio

There would be much to say about the impressive Castilian King Alfonso X (1252–1284) who made greatest efforts to bring together the various cultures, religions, and races at his court in Toledo. He composed both major poetry, such as his Galician Cantigas de Santa Maria, and had some scribes create major law books, his Fuero Real and his Siete Partidas. He is also well remembered until today for his impressive book of games, his Libros del ajedrez, dados y tablas (1283), in which the three types of games, represented by playing with dice, backgammon, and chess, are closely discussed and explained. Dice is determined by fortune, chess is a game of intellectual skill, and backgammon combines both aspects in one.

Among the many illustrations showing various members of his court, we also find, for instance, on fol. 22r, a group of noble (?) black chess players who are entertained by a (female?) musician performing on a hand-held harp; the entire group is shown to be involved in intensive debates over a chess problem, and in that regard this setting does not differ from all the others in this famous chess treatise. For instance, on fol. 25v, two representatives of monastic orders debate certain moves on the board; on fol. 33v, two male adult men instruct two boys how to play chess; on fol. 40r, a noble lady debates with a noble courtier about a chess figure, which she holds in her right hand; on fol. 41r, two Arabic-looking men exchange their ideas about the chess game, the one on the right holding a book in his right hand which might contain instructions about the game itself, just as on fol. 45v where the judge on the right side has placed a manuscript with Arabic letters on his lap; and on fol. 63r two Oriental-looking men discuss with each other over the development of the game, considering a particular setting or problem, etc., with the man on the left possibly a Jew and the one on the right a Muslim, judging by their headgears. Chess is thus described here as a playful but essential medium for communication among equal-minded individuals who share the same interest and culture, education and passion, and this obviously in utter disregard of their different religious or racial backgrounds.

There is no indication whatsoever that the king would have tolerated any negative depiction of Arabs and Blacks in his highly representative work (Alfonso X; cf. Kennedy 2019). Instead, these black players are identified as worthy individuals who apparently understand that game well and hence also deserved a dignified space in this splendid luxury manuscript. It seems as if Alfonso deliberately ordered his illuminators to incorporate this scene because he wanted to demonstrate to his public – it is unclear who might have even been allowed to view and study this valuable manuscript – that all races were welcome at his court. Altogether, however, there is only one scene involving blacks, and it would be dangerous to characterize this king as a forerunner of modern tolerance, as much as he allowed Blacks to be depicted in positive terms (García Arenal 1985; Klein 2007).

From here, we could easily expand the search for similar images, both from the early and the late Middle Ages. Biblical scenes depicted in medieval manuscripts, for instance, at times contain also Blacks, such as the Ashburnham Pentateuch from the late sixth or early seventh century (Paris, BnF, MS nouv. acq. lat. 2334, f. 21r; https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53019392c.image) (Pastoureau 2009).

Conrad Kyeser

In the remarkable manuscript by the Eichstätt engineer and artist, Conrad Kyeser, containing his Bellifortis (1405), we do not only come across a large number of drawings of weapons, tools, siege engines, belts, locks, and the like, but also a drawing of the black Queen Saba, or Sheba (Kyeser 1967, vol. 1, fol. 122 r; for a b/w reproduction, see the frontispiece in Mielke 1992; for an excellent overview of this queen’s mythical origin, her role in medieval and early modern art, and in modern cinema and theater, along with numerous illustrations, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_of_Sheba). She takes on the typical pose of a Gothic lady, with her body slightly curved in the form of an S; wearing a splendid dress in green, with ermine fur sowed at the edges, a crown, a scepter in her left hand, and an object topped with a cross. Her neck, face, and hands reveal her black skin. She wears a heavy necklace, and there is nothing about her that would describe her in any negative light. Instead, she completely conforms with the standard ideals of a courtly lady, except that she is black. This queen leaves a stunning impression of a most attractive person, whose dark brown skin color pleasantly harmonizes with her silk dress. Curiously, however, Kyeser included only this one black person in his entire Bellifortis (Quard 1967, vol. 2 of Kyeser 1967, 90). Until today, her image is regularly reproduced online as a significant illustration of this famous queen, such as in National Geographic (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/mysterious-queen-sheba-legend-church-archaeology).

The Black Balthazar

Since the late fourteenth century, black figures appear in German visual arts, in coats of art, and altar pieces, normally depicting the black Magi, one of the Three Holy Magi, identified only since the tenth century as Balthazar. As Paul H. D. Kaplan emphasizes, “The Black magus/king was a predominantly positive character entwined in a web of attitudes which could damage as well as support the position of Black people in European society” (1992, 119). There are countless examples depicting a dignified Balthazar, especially since the late fourteenth century, especially within the framework of the Holy Roman Empire, if we think of artists such as Hans Multscher (ca. 1400–1467), Georges Trubert (fl. 1469–1508), Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450–1516), Hugo van der Goes (ca. 1440–1482), Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1460–1465), and Hans Memling (1430/40–1494) (Collins and Keene 2023). Of course, as one of the Three Holy Magi, Balthazar assumed a special place in the biblical story and was hence not viewed the same way as a black knight was as discussed in literary texts, or in reality. Much depended on the person’s individual history or religious role, which explains the significant respect paid to the first martyr, a black man, St. Maurice, a sculpture of whom was even placed in the Magdeburg cathedral (ca. 1230; for a depiction, see Collins and Keene, ed., 2023, fig. 13, p. 12; for broader perspectives, see Devisse 1979).

Maurice was a Roman general of African background and died, along with his entire legion, the death of a martyr in 290 C.E. Later he even became the patron saint of the Kingdom of Burgundy in 888 and of the Holy Roman Empire in the tenth century. Since then, countless images or sculptures of him were created, and his name serves until today for apothecaries in Germany, for instance, and for towns, churches, and altars in Switzerland and France. Numerous chivalric orders carry his name, and he is also the patron saint of the Duchy of Savoy in France and of the Valais in Switzerland as well as of soldiers, swordsmiths, armies, and infantrymen. Moreover, he is the patron saint of the Brotherhood of Blackheads (Latvia and Lithuania) and of the Franconian town of Coburg in northern Bavaria (for more details and good images, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Maurice; cf. also Suckale-Redlefsen 1987). Current research has actually rediscovered the topic of Blacks in portraits from the late Middle Ages to the present (Brathwaite 2023) and uses the poignant term of ‘Black diaspora.’ Indeed, there remains much to be explored further (https://www.getty.edu/news/rediscovering-black-portraiture-through-the-getty-museum-challenge/; last accessed on March 6, 2023).

Conclusion

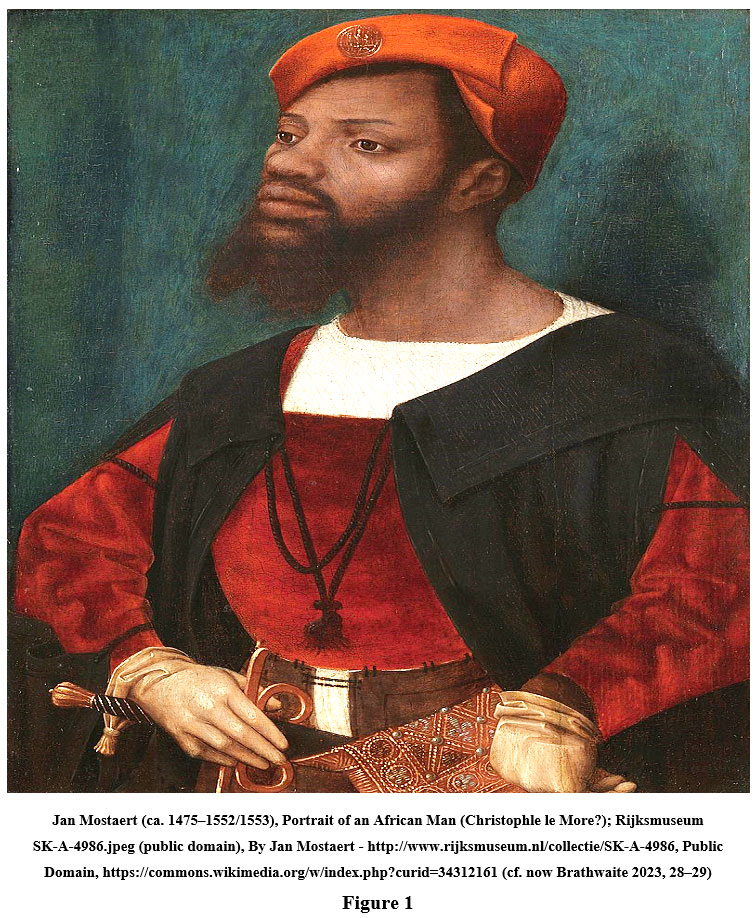

Around 1525 to 1530, the Dutch painter Jan Mostaert created a stunning portrait of a black soldier, perhaps even a high-ranking officer. Although art historians have not been able fully to identify the person portrayed here, he is certainly presented in a most impressive, almost admirable fashion, not giving an inch to racism. As Collins and Keene (2023, 84) now conclude, “the subject of this painting makes clear that members of the African diaspora mingled with white Europeans in royal courts at the same time that images of a Black king Balthazar proliferated.” To this amazing portrait we can add also a major painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder from 1520–1525 and of Matthias Grünewald from ca. 1520–1524 showing St. Maurice in a most fashionable Renaissance appearance, highly dignified, with blackness serving only as a distinctive feature of this attractive man.

There is a certain carelessness combined with a political agenda to use the term ‘racism’ in an inflationary manner, and to work in an anachronistic fashion of equating modern-day racism with the phenomena (plural!) that we can observe in the past. As Vanitha Seth now comments, “What is clear, however, is that in the European Middle Ages, ‘black’ and ‘white’ were charged descriptors that often conveyed moral meaning” (Seth 2020; online). In my selection of texts and images, most of the black individuals are outstanding personalities who attract much attention and even admiration (!).

Undoubtedly, this probably did not reflect the general attitudes toward blackness, especially because medieval societies were still much less exposed to the meetings of people of different skin color than our world today. Our evidence points in the direction that the ideology of racism was not yet fully developed, and within this vacuum, poets and artists discovered opportunities to describe Blacks simply as physically slightly others, but not at all in ethical or moral terms. However, as economic historians have now also demonstrated, already during the Middle Ages, economic trade connected the various West African kingdoms with the Mediterranean and hence the countries north of the Alps (Guérin 2017), so there are good chances to expect that also black merchants, diplomats, artists, and others traveled north and met their counterparts at trading places along the shore.

When the Priest Konrad talks about the evil and vicious black prince in Marsilie’s army, for instance, he simply belonged to the broad category of non-Christians who threatened the Christian world and who were thus automatically viewed as ‘evil.’ In short, I seriously question that the Middle Ages already knew a form of systematic racism as it emerged in the modern age, maybe as late as in the nineteenth century.

After all, in the eighteenth century, it was still possible that the young slave boy Anton Wilhelm Amo (ca. 1703–ca. 1759), who had originated from what we call today Ghana – he was a member of the Nzema – could be raised at the court of Anthony Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1633–1714) and then was allowed to enter first the university of Halle and then the university of Wittenberg where he earned his doctorate in 1734. He subsequently held a position as a professor of philosophy in Halle in 1736, and in 1740 in Jena, but finally left Germany certainly under racist harassment and political duress and returned to his homeland in 1747 (Abraham 1996; Ette 2014/2020). As Wulf D. Hund points out, since the seventeenth century, many aristocratic courts considered it fashionable to have a Black (“Mohr”) among the courtiers, who was mostly treated well, could even study, take on jobs, marry, and have children of their own, even though they would not have been considered as equal to the Whites (Hund 2017, 13–18).

I do not need to address in our context racism as it evolved ever since and as important and impactful it has been until today especially for those affected by it; instead, it is possible to conclude that it is certainly important to turn to the Middle Ages when black individuals already emerged on the mental horizon and assumed both negative and positive positions and characteristics. Already then, the ordinary people were apparently deeply scared of the Blacks out of religious reasons, equating them with the devil, but both courtly poets (twelfth and thirteenth centuries) and many different artists (especially since the fifteenth century) were remarkably open enough to include at times significant black individuals, and occasionally even as protagonists within the narratives or in the visual presentation.

In other words, if we want to understand racism and its historical evolution, we must also recognize and acknowledge the rather complex and much more diverse conditions vis-à-vis black contemporaries in the pre-modern world when race only began to enter the public discourse.

In the heroic epic Kudrun (ca. 1260, ed. 2000), for instance, one of the warriors wooing for Kudrun’s hand is identified as “Sîfrit, der künic von Morlant” (stanza 608, 1; Siegfried of Moorland; see the commentary by Gibbs and Johnson, trans., 1992, 174), as if he were black. But it might be only a form of name dropping with no further significance because the entire epic takes place in Nordic countries. We could also extend our research into the history of antiquity when racial issues certainly already existed, but then the pre-Christian, mostly Roman context was still very different (Bell 2021; Bell 2022).

It remains to be seen whether Wolfram von Eschenbach and the anonymous Dutch author of the Romance of Moriaen were unique exceptions, or whether they reflected more widespread attitudes toward Blacks, at least within the world of the medieval courts. We can be certain that a direct equation of modern racism with medieval attitudes toward Blacks would be a dangerous fallacy and undermine the critical approach to the various texts, images, and sculptures from that time period. However, there are good reasons to assume that incipient forms of racism were already shaping up in the pre-modern era, as much as poets and artists still embraced the idea at times that Blacks were to be treated as worthy and dignified members of the courtly world.

However, environmental determinism was very much at play as well, and this already since antiquity, and so certainly also during the Middle Ages. Hence, racism primarily targeted people at the margin, not necessarily only Blacks who actually did not yet appear as a social group as such on the mental map of the average European until maybe the eighteenth century. For the Anglo-Normans, for instance, their racial targets were the Irish, for Christians overall, the racial minorities were Muslims and Jews; western Europeans racialized the Huns, and so forth (Weeda 2021; for a review, see Wade 2023). In short, potentialities for racist thinking have existed throughout time, or at least thinking in terms of race. This forces us to discriminate considerably and to operate rather carefully with respect to racial relationships in the pre-modern world. Those who subscribe to the theoretical school of ‘RaceB4Race’ (https://www.ayannathompson.com/raceb4race) might have to do a bit more soul-searching and analysis of the actual documents and general evidence from that time period before they can really employ the modern term of ‘racism’ for that culture. They might suffer from an anachronistic fallacy, as popular as their conferences and other academic activities might have been. Medieval and Early Modern Studies are no longer the true focus of that Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies; those have been, alas, replaced by a more politicized approach.

I would like to express my gratitude to Elizabeth Mazzola for her extensive and constructive review of this article in a pre-print format, online at Qeios, Feb. 15, 2023; https://www.qeios.com/read/AGEUBW. I also received further comments and valuable criticism on the same website: https://www.qeios.com/notifications; the article obviously engendered a lot of interest even before it was published. See specifically the comments by Luiz Valério P. Trindade “Given the fact that most of the critical race theory (CRT) literature focuses on contemporary societies and the colonial legacy in shaping current racial relations, this article brings a fresh and innovative perspective by addressing the topic in the historical context of the middle ages [sic]. That is, it changes our standpoint and sheds light on the critical analysis of racism in ways not commonly seen in many studies.” https://www.qeios.com/read/AQZ8C1#comments (Feb. 27, 2023).

|

Figure 1 Click here to view Figure |

References

- Abraham, William E. (1996) “The Life and Times of Anton Wilhelm Amo, the First African (Black) Philosopher in Europe.” African Intellectual Heritage: A Book of Sources, ed. Molefi Kete Asante and Abu S. Abarry. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 424–40.

- Alexander, M. (2010/2020) The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness New York and London: The New Press.

- Alfonso X el Sabio., King of Castile and Leon. (1987) Libros de ajedrez, dados y tablas. 2 vols. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional. Transcription from the original by Mechthild Crombach.

- Baldwin, J. & Margaret M. (197). A Rap on Race. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott.

- Bancourt, P. (1982) Les Musulmans dans les Chansons de Geste du Cycle du Roi. Marseille, Aix-en-Provence, et al.: Université de Provence.

- Baumgärtner, I. Forthcoming. “Mapping Narrations – Narrating Maps: Concepts of the World in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period.” Research in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications.

- Bell, Sinclair W. “Images and Interpretation of Africans in Roman Art and Social Practice.” The Oxford Handbook of Roman Imagery and Iconography, ed. Lea Cline and Nathan T. Elkins. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022, 425–63.

CrossRef - Bell, Sinclair W. “Images and Interpretation of Africans in Roman Art and Social Practice.” The Oxford Handbook of Roman Imagery and Iconography, ed. Lea K. Cline, and Nathan T. Elkins. 2021. Online ed. Oxford Academic, 8 Dec. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190850326.013.25, last accessed on Feb. 27, 2023.

CrossRef - Birkhan, H., trans. (2001) Leben und Abenteuer des großen Königs Apollonius von Tyrus zu Land und zur See. Ein Abenteuerroman von Heinrich von Neustadt verfaßt zu Wien um 1300 nach Gottes Geburt. Bern, Berlin, et al.: Peter Lang

- Borgolte, M. (2022) Die Welten des Mittelalters: Globalgeschichte eines Jahrtausends. Munich: C. H. Beck.

CrossRef - Brandsma, Frank, McFadyen J., & Leah Tether. 2017. “The Roman van Walewein and Moriaen: Travelling through Landscapes and Foreign Countries.” Handbook of Arthurian Romance: King Arthur’s Court in Medieval European Literature, ed. Leah Tether, Johnny McFadyen, Keith Busby, and Ad Putter. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 415–30

CrossRef - Brathwaite, P. (2023) Rediscovering Black Portraiture. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Braude, B. (1997) “The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods,” The William and Mary Quarterly 54.1, 103–42.

CrossRef - Brüggen, E. (2014) “Belacâne, Feirefîz und die anderen: zur Narrativierung von Kulturkontakten im ‘Parzival’ Wolframs von Eschenbach.” Figuren des Globalen: Weltbezug und Welterzeugung in Literatur, Kunst und Medien, ed. Christian Moser and Linda Simonis . Göttingen: V&R unipress, 673–92.

CrossRef - Brüggen, E. & Bumke J. (2011) “Figuren-Lexikon.” Wolfram von Eschenbach: Ein Handbuch, ed. Joachim Heinzle. Vol. II. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 835–938.

CrossRef - Bumke, Joachim. 2004. Wolfram von Eschenbach. 8th completely rev. ed. Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler.

CrossRef - Burmester, S. & Howard C. L. (2022) “Confronting Book Banning and Assumed Curricular Neutrality: A Critical Inquiry Framework.” Theory Into Practice 61.4 (2022): 373–83.

CrossRef - Collins, Kristen and Bryan C. Keene, ed. (2023) Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Collins, Kristen and Bryan C. Keene. (2023) “An African King in Art and Legend.” Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1–33.

- Crenshaw, K. W., ed. (2019) Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness across the Disciplines. Berkeley: University of California Press.

CrossRef - Dadabhoy, Ambereen, & Mehdizadeh N. (2023) Anti-Racist Shakespeare. Elements in Shakespeare and Pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CrossRef - Darrup, Cathy C. (1999) “Gender, Skin Color and the Power of Place in the Medieval Dutch Romance of Moriaen,” Medieval Feminist Newsletter 27, 15–24; online at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1329&context=mff.

CrossRef - Jacques Devisse. (1979) L’Image du Noir dans l’Art Occidental. 2 vols. Paris: Gallimard.

- DeWeever, J. (1990) “Candace in the Alexander Romances: Variations on the Portrait Theme.” Romance Philology 43, 529–46.

- Duggan, Joseph and Annalee C. Rejhon, trans. (2012) The Song of Roland: Translations of the Versions in Assonance and Rhyme of the Chanson de Roland. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Earle, T. F., and K. J. P. Lowe, ed. (2005) Black Africans in Renaissance Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ebenbauer, A. (1984) “Es gibt ain mörynne vil dick susse mynne: Belakanes Landsleute in der deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters.” Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur 113, 16–42.

- Eliav-Feldon, Miriam, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler, ed. (2009) The Origins of Racism in the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ekotto, F. (2023) “Talking Race.“ MLA Newsletter 55.2, 1–3.

- Ette, Ottmar. (2014/2020) “Anton Wilhelm Amo – Philosophieren ohne festen Wohnsitz: eine Philosophie der Aufklärung zwischen Europa und Afrika.” 2nd ed. Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos.

- Finet-Van Der Schaaf, Baukje, ed. and trans. (2009) “Le roman de Moriaen/Roman van Moriaen.” Moyen âge européen. Grenoble: ELLUG.

CrossRef - Frisch, Max. (1961) Andorra. Stück in zwölf Bildern. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

- Garcí Arenal, Mercedes. (1985) “Los moros en las cantigas de Alfonso X El Sabio.” Al-Qantara VI, 133–51.

- Gray, C. (1974) “The Symbolic Role of Wolfram’s Feirefiz.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 73.3, 363–74.

- Guérin, Sarah M. (2017) “Exchange of Sacrifices: West Africa in the Medieval World of Goods.” The Medieval Globe 3.2, 97–123.

CrossRef - Hartmann, H. (2015) Einführung in das Werk Wolframs von Eschenbach. Einführungen Germanistik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Hendricks, M. (2021) “Coloring the Past, Considerations on Our Future: RaceB4Race,” New Literary History 52.3: 365–84.

CrossRef - Heng, G. (2018) “The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CrossRef - Hermans, E., ed. (2020) “A Companion to the Global Early Middle Ages. Leeds”: Arc Humanities Press.

CrossRef - Hsy, J. (2021) “Antiracist Medievalisms: From “Yellow Peril” to Black Lives Matter.” Leeds: Arc Humanities Press.

CrossRef - Hsy, J. & Orlemanski J., ed. (2017) “Race and Medieval Studies, a Partial Bibliography.” Postmedieval 8.4 (2017): 500–531; https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-017-0072-0

CrossRef - Hund, Wulf D. (2017) “Wie die Deutschen weiss wurden: Kleine (Heimat)Geschichte des Rassismus. ” Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

CrossRef - Kaplan, M. L. (2018) “Figuring Racism in Medieval Christianity.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CrossRef - Kaplan Paul H. D. (1985) “The Role of the Black Magus in Western Art: Studies in the Fine Arts: Iconography.” Ann Arbur, MI: UMI Research Press.

- Kennedy, K. (2019) Alfonso X of Castile-León: Royal Patronage, Self-Promotion and Manuscripts in Thirteenth-century Spain. Church, Faith and Culture in the Medieval West. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

CrossRef - Kim, D. (2019) “Introduction to Literature Compass Special Cluster: Critical Race and the Middle Ages.” Literature Compass 16.9–10, 1–16; https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12549

CrossRef - Klein, Peter K. (2007) “La imagen de los moros y los judíos en las Cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio.” Simposio Internacional. El legado de al-Andalus. El arte andalusí en los reinos de León y Castilla durante la Edad Media. Coord. y ed. M. Valdés Fernández. Valladolid: Fundación del Patrimonio Histórico de Castilla y León, 339–64.

CrossRef - Kudrun, ed. Karl Stackmann. (2000) Altdeutsche Textbibliothek, 115. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Kudrun, trans. Marion E. Gibbs and Sidney M. Johnson. (1998) Garland Library of Medieval Literature, Series B, 79. New York and London: Garland.

- Layne, P. & Thurman K. (2022) “Introduction: Black German Studies.” German Quarterly 95.4, Special Issue, 359–371.

CrossRef - Mellinkoff, Ruth. (1993) Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages. 2 vols. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Morera, Luis X. (2022) “Performative Subjugation and the Invention of Race: The Danzas de Judios y Moros, Festivals, and Ceremonies in Late Medieval Iberia,” Mediaevalia 43.1: Special Issue: Medieval Unfreedoms in Global Context, 205–38; DOI:10.1353/mdi.0.0007.

CrossRef - Kenney, Kirstin. (2019) Alfonso X of Castile-León: Royal Patronage, Self-Promotion and Manuscripts in Thirteenth-Century Spain. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

CrossRef - Kyeser, Conrad. (1967) Bellifortis. Vol. 1: Facsimile-Druck der Pergament-Handschrift Cod. Ms. philos. 63 der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen. Vol. 2: Umschrift und Übersetzung by Götz Quarg. Düsseldorf, VDI-Verlag.

CrossRef - Opitz, May. (1992) “Racism, Sexism, and Precolonial Images of Africa in Germany.” Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out, ed. Katharina Oguntoye, May Opitz, and Dagmar Schultz. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1–76.

- Pastoureau, Michael. (2009) Black: The History of a Color. Princeton, NJ : Princeton University Press.

- Patton, Pamela A., Perry D., & Heng G. (2019) “Blackness, Whiteness, and the Idea of Race in Medieval European Art,” Whose Middle Ages? Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past, ed. Andrew Albin, Mary C. Erler, Thomas O’Donnell, Nicholas L. Paul, and Nina Rowe. New York: Fordham University Press, 154–65.

CrossRef - Pfeffer, Wendy, ed. (2022) Blandin de Cornoalha: A Comic Occitan Romance. A New Critical Edition and Translation, trans. by Margaret Burrell and Wendy Pfeffer. TEAMS Varia Series. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications.

CrossRef - Rambaran-Olm, Mary and Erik Wade. (2022) “What’s in a Name? The Past and Present Racism in ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Studies,” Yearbook of English Studies 52: 135–53.

CrossRef - Ramey, Lynn T. (2014) Black Legacies: Race and the European Middle Ages. Gainesville, Tallahassee, et al., FL: University Press of Florida.

CrossRef - Seth, V. (2020) “The Origins of Racism: A Critique of the History of Ideas,” History & Theory 59.3, 343–68; DOI: 10.1111/hith.12163.

CrossRef - Stovall, T. (2021) White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea: The Racist Legacy Behind the Western Idea of Freedom. Race, Justice & Equity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

CrossRef - Suckale-Redlefsen, Gude. (1987) Mauritius: Der heilige Mohr. The Black Saint Maurice. Munich: Schnell und Steiner/Houston: Menil Foundation.

- Tinsley, David F. (2011) “Mapping the Muslims: Images of Islam in Middle High German Literature of the Thirteenth Century.” Contextualizing the Muslim Other in Medieval Christian Discourse, ed. Jerold C. Frakes. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 65–101.

CrossRef - Wade, Erik. (2023) Review of Weeda, Claire. 2021. Ethnicity in Medieval Europe. In The Medieval Review, TMR 23.03.15, online.

- Walcott, R. (2014) “The Problem of the Human: Black Ontologies and ‘the Coloniality of Our Being.’” Postcoloniality – Decoloniality – Black Critique: Joints and Fissures, ed. Sabine Broeck and Carsten Junker. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus, 2014, 93–105.

- Weeda, Claire. (2021) Ethnicity in Medieval Europe, 950–1250: Medicine, Power and Religion. Health and Healing in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge, UK: York Medieval Press.

CrossRef - Wells, D. A. (1971) “The Middle Dutch Moriaen, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, and Medieval Tradition.” Studia Neerlandica 2, 243–81.

- Wolfram von Eschenbach. (2004/2006) Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival and Titurel, trans. and notes by Cyril Edwards. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wolfram von Eschenbach. (1998) Parzival. Studienausgabe. Mittelhochdeutscher Text nach der sechsten Ausgabe von Karl Lachmann. Übersetzung von Peter Knecht. Einführung zum Text von Bernd Schirok. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.